From green roofs on new buildings, to quantifying visitors (beyond counting toilet paper rolls), to how much to mow, here are some notable ideas to emerge from the 2023 Park People conference in Toronto.

(Second of a series – see People passionate about parks gather in Toronto for the first)

Up on the roof

As the forest of condos in downtown Toronto grows ever higher and denser, new parks are being created on rooftops.

Case in point: I visited the rooftop park on Canoe Landing Community Centre at 45 Fort York Boulevard in downtown Toronto, where the Park People conference is being hosted. The community centre officially opened in 2021. Its rooftop has a basketball court, running track, and raised beds for a community garden. Flowers to attract pollinators, tomatoes, chives, pumpkins, and broccoli were flourishing. Colourful Muskoka chairs were lined up along the glass railing providing views of the CN Tower, Canoe Landing Park, and the Gardiner Expressway. So in addition to its environmental benefits, the green roof at the community centre has created a new space for recreation and an oasis from the traffic below.

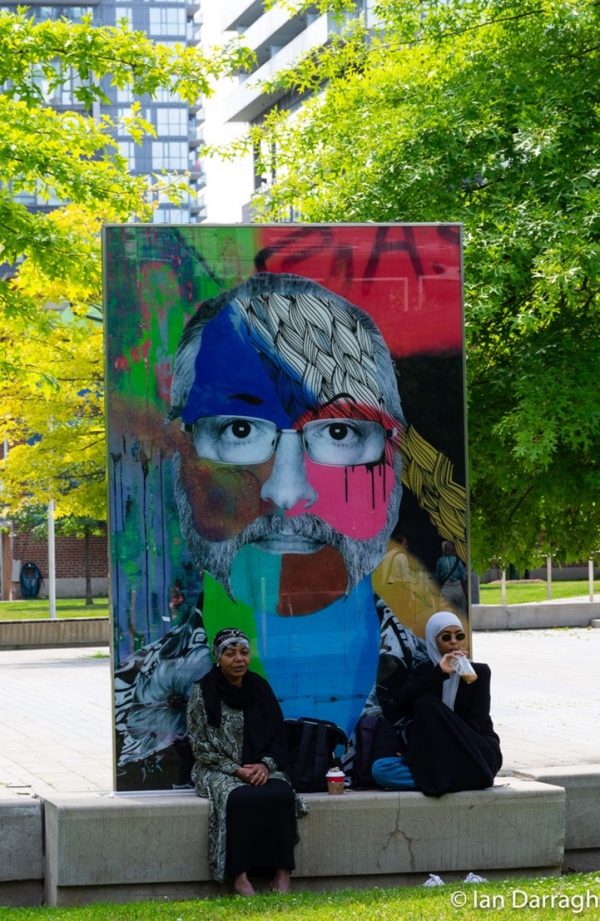

We were taken on a field trip to Regent Park, a neighbourhood in downtown Toronto that underwent a massive redevelopment starting in 2005. My last visit to Regent Park was in 2015, when I organized a poetry reading by George Elliott Clarke at the Daniels Spectrum arts centre for Black History Month. I was curious to see how well all the new facilities at Regent Park have aged. Fortunately, I was not disappointed.

Our guides were Lucky Boothe, a City of Toronto recreation supervisor, and Sean Brathwaite of Friends of Regent Park. A highlight of the tour was the Regent Park Community Centre. Its facilities include a climbing wall, indoor track, and basketball courts with gleaming wood floors. We trooped up the stairs to the community garden on the roof. Connected to the community centre is Nelson Mandela Park Public School, and its students have an opportunity to grow vegetables in the rooftop garden. From the rooftop, we could see children playing soccer and taking a physical education class. In Regent Park itself, children were playing games and volunteers from Friends of Regent Park were baking scones in an outdoor wood-fired oven. The neighbourhood was bustling.

Sean Brathwaite told us that the mix of subsidized and market-value condos in redeveloped Regent Park has been so successful that requests for proposals have been made to construct two more condo towers. New parks will likely be designed on the rooftops of these buildings, since there is no more vacant land available for green space at street level. Before the redevelopment, there were no banks or services in Regent Park. Now banks, a pharmacy and other retailers have opened stores on the ground floors of some of the residential towers. St. Michael’s Hospital has opened a clinic and George Brown College has a satellite campus. Residents of Regent Park finally have access to services in their neighbourhood. Sean told us a few market-based condos have sold for over a million dollars, proving that Regent Park is now a desirable neighbourhood to live in, and another indicator of the high cost of real estate in downtown Toronto.

By the numbers

Until recently park planners had no real idea how many people visit a particular city park. While most provincial and national parks are isolated and have a limited number of road access points, most urban parks have multiple entrances. Visitors can travel to a city park on foot, skateboard, roller blade, or bicycle, or arrive by motor vehicle using multiple access points. City parks are most heavily used in the early morning, evening, and on weekends. Hiring students to survey park usage is impractical.

If a city park has washrooms, some park planners tracked how many rolls of toilet paper were used per year to gauge how popular the park was. The problem with this crude metric is that many parks close their brick and mortar washrooms in winter, and males often use no toilet paper when they visit the washroom.

Concerned about the growing volume of motor vehicle traffic in Stanley Park, the city of Vancouver is now using sensors, anonymous smartphone data, and parking meter data to track the number of visitors to the park, modes of transportation, and traffic patterns. This is the first time that hard data has been available about how visitors access the park and where they go. The Stanley Park Mobility Study has so far uncovered one astounding fact. Before the study, the annual number of visits to Stanley Park was estimated to be around 10 million. In 2021, the mobility study recorded 18 million visits to the park.

“Tracking visitor behaviour using electronic sources has the potential to revolutionize park planning,” says Dave Hutch, deputy director of parks and public spaces with the City of North Vancouver, and formerly with the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation. “This data will enable us to protect sensitive areas of a park and plan resources.” No more counting rolls of toilet paper.

Having the ability to obtain hard numbers about the popularity of city parks will finally provide park advocates with ammunition to argue for more funding to maintain green spaces in our cities. As activist Dave Meslin told the Park People Conference in his keynote address: the problem with urban parks and public spaces is they have no lobby groups or broad public constituency to protect them. If a school board or a provincial government makes changes to the curriculum or the services offered by a school, parents, teachers, and unions will rise up in protest. If cities gradually pinch the operational budgets for maintaining urban parks, who will lobby against overflowing trash cans and dirty washrooms? Having hard data about how city parks are used will be a game changer.

To mow or not to mow?

You may have noticed that the grass is not being cut in certain areas of your local city park. It’s a trend called creating pollinator meadows, or rewilding certain areas of parks.

Kathleen Watson, a landscape architect from Ottawa, highlighted “rewilding” as the most important takeaway from the conference so far.

Grass needs to be cut for soccer pitches and other playing fields. But park planners are discovering the environmental benefits of not mowing under trees, along borders and on steep slopes. Allowing flowers (including weeds) to bloom creates sources of nectar for bees and other insects. Allowing milkweed to grow provides food for endangered monarch caterpillars. Close-cropped lawns are biological deserts. In contrast, meadows are rich in wildlife, creating habitat for birds, reptiles, and mammals. An added benefit is that longer grasses preserve the moisture in the soil. And parks departments can save money on fuel and lower carbon emissions by reducing the amount of grass in parks that is being mowed every month in summer.

Ian Darragh is a former editor-in-chief of Canadian Geographic magazine.

All photos by Ian Darragh.