Portraits of Queen West: Spadina to Bathurst is being published through a crowdfunding campaign that launches today. Check the campaign website for updates.

This book is a love letter to Queen Street West by a photographer living in exile — one driven to leave the street he loves by the same gentrification and condoization that has so transformed this iconic west-end Toronto neighbourhood.

Kevin Steele grew up in Saskatoon, Sask. His first taste of Queen Street West was in the 1970s, when he often visited his father, who lived in the neighbourhood and was an activist with the League for Social Action. “My dad let me run free. I would hang out at Bakka, a science fiction book store, and the Silver Snail, which sold comics. Queen Street was my mecca.”

Steele enrolled at the Ontario College of Art (as it was then known) in the early 1980s, and then founded one of Toronto’s first desktop graphics studios, called Mackerel. He started making photos of Queen West with a Nikon Coolpix in the 2000s. He loved the way digital photography gave him the ability to capture images inexpensively. “I was a witness to massive changes all around me on Queen West. I’d go back to the same spot, and, within a few days, things had already changed.”

Portraits of Queen West: Spadina to Bathurst’s genesis was an exhibit at the Gladstone Hotel. Steele had photographed Queen West from Gladstone east to Lisgar Street in 2003, before the Gladstone or Drake hotels were renovated. In 2006, he re-photographed the same blocks after the Gladstone was refurbished, and his exhibit captured the dramatic before-and-after changes.

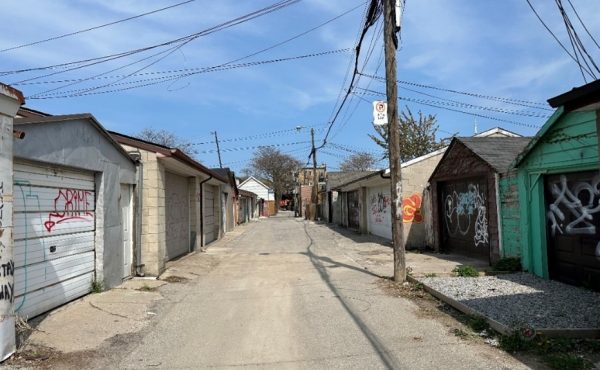

Among the book’s highlights are images of a six-alarm fire on the south side of Queen West, between Portland and Bathurst streets, on February 20, 2008, that gutted a row of heritage buildings, proving that despite advances in smoke alarms and fire-fighting equipment, fire remains a major threat to Toronto’s built heritage. Other gems are photos of the “secret swing” off Graffiti Alley, portraits of a couple kissing passionately on a bench, and the reflection series of streetscapes first published in Spacing magazine in 2011 and 2021.

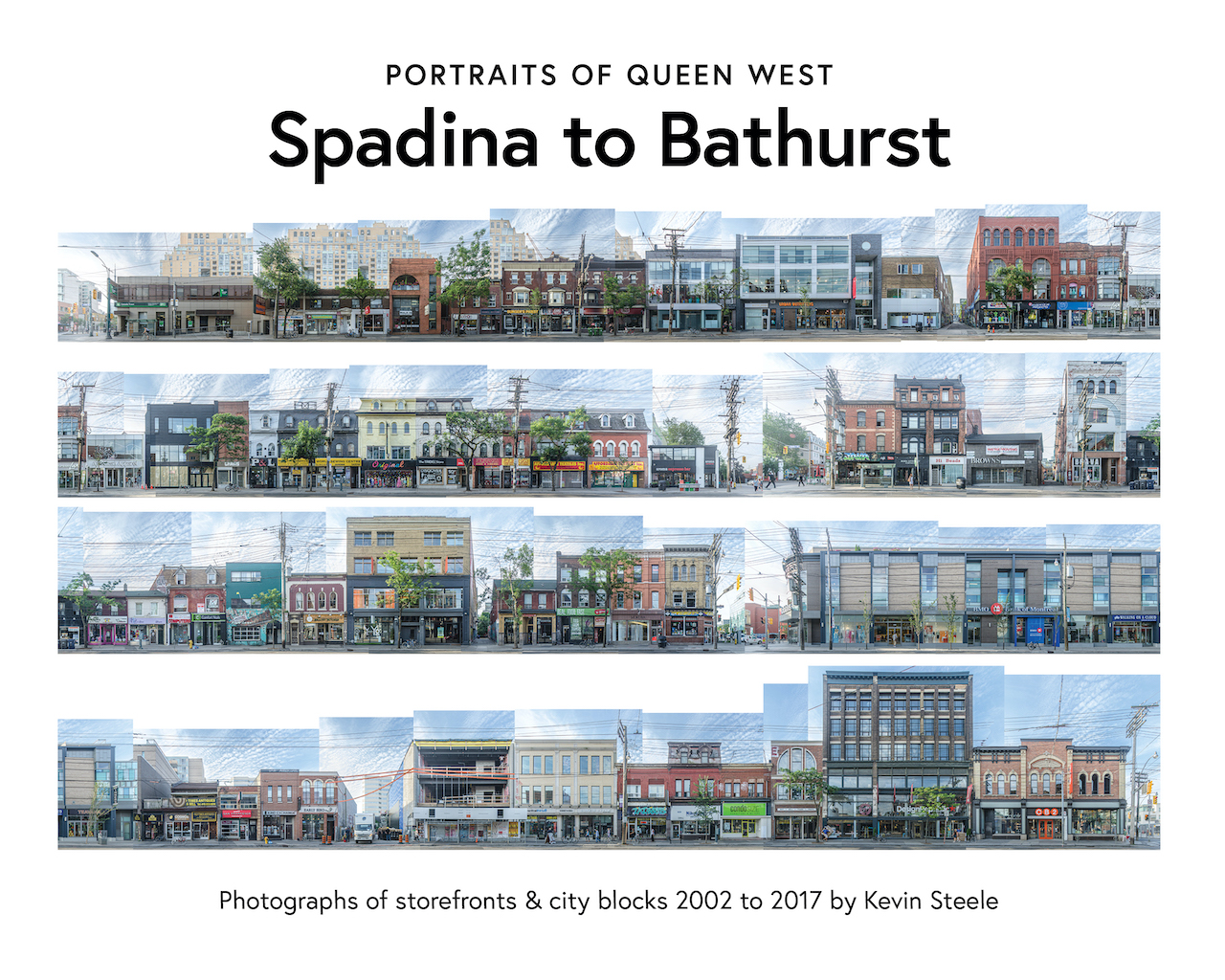

In many of Steele’s collages there is a strange absence of pedestrians and traffic. He has worked hard to take these images when storefronts were unobstructed by people, parked cars, or the Queen streetcar. His focus (and obsession?) is firmly on the storefronts, and the book delivers on its subtitle: Photos of storefronts & city blocks 2002-2017.

Steele describes his technique: he waits for breaks in the traffic, then darts out to snap an image when storefronts are unobstructed; he edits his images in Lightroom, adjusting the perspective to make the buildings vertical; and, finally, he stitches the photos in Photoshop. Steele doesn’t try to mask that his linear composites are made of photos taken at different times: frames are ragged, cars are chopped off and power lines don’t match up. I like the honesty of his composites. He isn’t trying to hide anything. He’s captured Queen West’s grittiness. In subsequent books, Steele might consider adding night shots and scenes in a variety of weather, such as snowstorms, to reflect Queen West’s many moods.

“In my last years in Toronto most of my money was going to pay rent,” Steele recalls. In 2017, he was forced to move back to Saskatoon. “It’s heart-breaking that I can’t figure out a way to live in Toronto.” His experience reflects the affordable-housing crisis that has driven so many artists out of the city they love.

Steele is planning more love letters about the street of his dreams. A hundred years from now, these books will no doubt be a vital record of one of Toronto’s iconic streets.