The current housing crunch is far from the first that Toronto has experienced. This story, originally published on Torontoist on September 11, 2013, looks at the pioneering efforts of the Toronto Housing Company to create affordable housing over a century ago.

“This is not a company; it is a cause.”

When the Toronto Housing Company (THC) issued its first annual report (quoted above) in 1913, its directors saw themselves as more than a private-public partnership dedicated to building affordable worker housing. They adopted a crusading tone in order to help spread across the country the gospel of planning quality home developments for low-wage earners. Though their efforts fizzled, the two projects THC built proved sturdy enough to survive into the 21st century: Spruce Court and the Bain Co-op (which was originally known as Riverdale Courts).

The two complexes were built in response to a housing crunch that hit Toronto during the early 20th century. The city’s infrastructure, especially its transportation infrastructure, couldn’t keep up with the city’s physical expansion and population growth. Land prices in the core rose so much that a 1907 survey of 43 families showed that their rents had risen by 95 percent over the previous decade. Low-income families were crammed into inadequately sized dwellings where sanitation often consisted of a single outhouse for dozens of residents. Fears about the spread of slums were heightened when Chief Medical Officer Dr. Charles Hastings issued a report in 1911 that declared the following:

It must be apparent that we are confronted with the existence of congested districts of insanitary, overcrowded dwellings, which are a menace to public health, affording hotbeds for germination and dissemination of disease, vice and crime. Municipality after municipality has been called upon to pay the penalty for neglected slums. The portion of this paid by human life and human suffering cannot be easily computed as the tax for hospital, prison and reformatory maintenance. We are more willing to supply this accommodation than to endeavour to stamp out the gardens of vice and crime, and the very hotbeds of disease. What we want is prevention, not cure. We can scarcely hope for people to rise much above their environments. Environment leaves its indelible records on mind, soul, and body.

Local reformers were attracted to “co-partnership” housing as a solution. Promoted across Canada by Governor-General (and football-trophy donator) Earl Grey and British MP Henry Vivian, this model mixed elements of co-operatives with a small, capped dividend offered to private shareholders. Co-partnership projects built in England tied into the “garden city” movement, which held that aesthetics were as important as function. Attractive architecture and courtyard landscaping created a healthier, more natural setting than did typical working-class row houses or slummy tenements. Garden cities and model towns were promoted as a means of maintaining productivity through healthier, happier workers. Ideally, these new settlements would be located on the edges of cities, where property was cheap and some agricultural land could be retained for food gardens.

These ideas influenced the directors of the THC, which arose in 1912 from a municipal committee seeking solutions to the housing crisis. Thanks to a provincial law passed the following year, the THC would be funded by a combination of City-authorized bonds and private subscriptions.

The THC assembled properties in both the city and the suburbs, though dreams of garden cities in the latter never materialized. The two city projects that went ahead offered residents “cottage flats,” which were described in a 1915 brochure for Riverdale Courts in the following way:

A cottage flat is a modern apartment with its own front door to the street. The Bain Avenue buildings of the Toronto Housing Company are arranged around three grass courts. There the small children will have ample room to play, where their parents can see them, and away from the dangers and the dust of the street. Each building consists of from two to nine houses; each house contains two cottage flats, one downstairs and one upstairs, that is, one on the ground floor, one on the first and second floors. The entire development is to be heated by steam from a central plant and the same plant will furnish hot water to every flat the year round. There are no dark or poorly ventilated rooms, because the buildings have a wide frontage, and are only two rooms deep, so that every room opens to the air and sunlight. Each flat has its separate bathroom, separate balcony or verandah and separate basement. Gas stoves, electric fixtures and window blinds are installed by the Company. In every kitchen there is an enamelled combination sink and laundry tub.

Rents included heat, water, and a fixed sum for repairs. If no work was necessary, tenants received the repair fund back as cash. Potential residents had to supply two character references in their application — a sign of the moral policing reformers of the era loved. It was felt that if residents had a deeper interest in their residential community, they’d pressure their wayward neighbours into conforming for the good of all. Messy tenants received little sympathy. The range of accepted residents included tradesmen, factory workers, department-store clerks, and Salvation Army evangelists.

The reformers on the THC board also believed they could improve the lot of recent immigrants, making them less scary to uptight Torontonians. As THC president G. Frank Beer observed in the company’s 1913 annual report:

These people are not different from ourselves, except in the lesser opportunities they have had for development of mind and soul. They are cheerful, virile, and in the main thrifty. Given the right environment, with the advantages of education, they will become true and valuable Canadians. I can see neither prudence nor justice in giving these people no better chances than they have today in Toronto to live in decent surroundings and healthful homes. It is not in the best interest of our city or our country that they should accept with cheerfulness or indifference a low level of living. At the present they form a menace to the health and morals of some localities and are said to affect injuriously the labour market. A better environment, better houses, better education and some human help can make of their children sturdy, worthy citizens, bringing strength, endurance, and talent as well to share in the great work ahead of us.

THC’s management and shareholders were a who’s who of Toronto business and industry (including members of the Eaton family, Joseph Flavelle, W.F. Maclean, William Mackenzie, and Edmund Osler), but they were genuinely interested in helping the poor. There were practical concerns behind their altruism, though. Many were involved in manufacturing, and so required a cheap pool of labour. If their workers were contented by attractive low-cost housing, they were less likely to press for higher wages or cause labour unrest. Businessmen like Beer also worried that a continued housing shortage would discourage people from moving to Toronto, cutting the supply of workers and reducing profits.

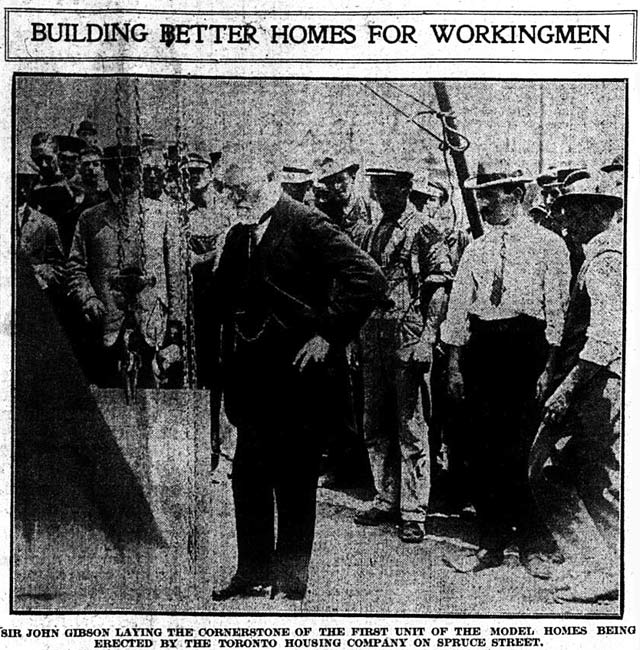

When the cornerstone laying for Spruce Court occurred in June 1913, the News declared that it was “one of the most important events in the social history of the city. Future generations will want to know to whom belongs the honour of checking the growth of slums in Toronto.” While THC’s complexes were well designed by Arts and Crafts-style practitioner Eden Smith and proved to be attractive, safe places to live, they didn’t curb the decay of nearby neighbourhoods like Cabbagetown. War, depressions, and other economic issues played havoc with THC’s funding, though additions were made to both Spruce Court and Riverdale Courts.

THC rents were lower than market value, but they still proved too high for many people to afford. The company never secured the magic combination of low-cost land, mortgages, and transportation necessary to fill the city with “homes for the people.” Riverdale Courts and Spruce Court passed into private ownership for a time and were threatened with condo development before becoming co-ops in the late 1970s.

Sources: Better Housing in Canada: First Annual Report of the Toronto Housing Company, Limited (Toronto: Toronto Housing Company, 1913), Cottage Flats at Riverdale Courts (Toronto: Toronto Housing Company, 1915), The Usable Urban Past: Planning and Politics in the Modern Canadian City, edited by Alan F.J. Artibise and Gilbert A. Stelter (Toronto: Macmillan, 1979), Unplanned Suburbs: Toronto’s American Tragedy 1900 to 1950 by Richard Harris (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), Report of Medical Officer of Health on Housing by Dr. Charles Hastings (Toronto: City of Toronto, 1918), Regent Park: A Study in Slum Clearance by Albert Rose (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1958), and the June 27, 1913 edition of the News.