We often grumble about how long it takes for large urban construction projects to be completed. But there was little time to grouse when it came to Maple Leaf Gardens, which was built in five months during the Great Depression. This article, an expanded version of one originally published on Torontoist on November 14, 2009, looks at the story behind the construction of this downtown Toronto landmark and how its opening night unfolded in 1931.

“The accolades were not out of place. There was simply nothing like Maple Leaf Gardens anywhere in Canada,” writer Kelly McParland observed in his biography of Conn Smythe. “It was more than just a step-up on the old, cramped, badly ventilated Arena Gardens; it was a generation or more ahead of any other building in the country. It was clean, comfortable, and welcoming.”

Built in an almost unimaginable span of five months, the building that became a temple for generations of hockey fans is a testament to the executives who used their persuasive skills to raise the necessary funds during the Great Depression.

From the dawn of the National Hockey League in 1917, its Toronto franchises had called the Arena Gardens on Mutual Street home. By the late 1920s, its small capacity (eight thousand seats) and lack of amenities like reliable heating led Smythe, the Maple Leafs’ general manager and part-owner, to push for a new facility at any opportunity. Larger arenas in Chicago, Detroit, and New York allowed those teams to offer higher salaries to top players, which made Smythe fear that Toronto’s limited financial resources would leave the team uncompetitive. He also felt the arena’s drawbacks prevented a higher-quality clientele from attending games. As he told the Star’s Greg Clark, “As a place to go all dressed up, we don’t compete with the comfort of theatres and other places where people can spend their money. We need a place where people can go in evening clothes, if they want to come there from a party or dinner. We need at least twelve thousand seats, everything new and clean, a place that people can be proud to take their wives or girlfriends to.”

By early 1931, Maple Leaf Gardens Limited was established to raise funds for a new building. The first site considered was at Yonge and Fleet (present-day Lake Shore Boulevard) on property owned by the Toronto Harbour Commission. The company then looked at land that had belonged to Knox College on Spadina Crescent north of College Street, but faced opposition from nearby businesses. The same site was part of an arena proposal made by a set of unrelated financial investors that was announced in early 1931, which was opposed by nearby residents spearheaded by future Toronto mayor Nathan Phillips and a pair of local clergymen. Smythe admitted the Spadina plan mystified him, but it provided the motivation to prod the team’s directors to speed up the site-finding process.

Smythe and Maple Leafs director Ed Bickle negotiated with Eaton’s throughout 1930. The department store opened its College Street location (now College Park) that year and was open to drawing more customers from a nearby arena, even if its clientele might not be the type of people they hoped to attract to their frou-frou new store. Eaton’s owned land along Church Street between Alexander and Wood streets, but there was one holdout lot within the land parcel. Charles Carmichael demanded $75,000 for his property at 60 Wood Street, even though its value was closer to $10,000. When Carmichael continued to hold out, discussions began over Eaton-owned property at Carlton and Church, a site Smythe preferred due to its direct access to streetcar service.

Negotiations dragged on for months, with Eaton’s proposing several ideas that kept the arena out of sight of the upper class clientele they wanted to bring into the neighbourhood, including workarounds on Wood Street to dodge Carmichael’s property. Bickle pointed out that the arena could serve plenty of useful other purposes, such as convention space, and even proposed naming the building “Eatonia Gardens.”

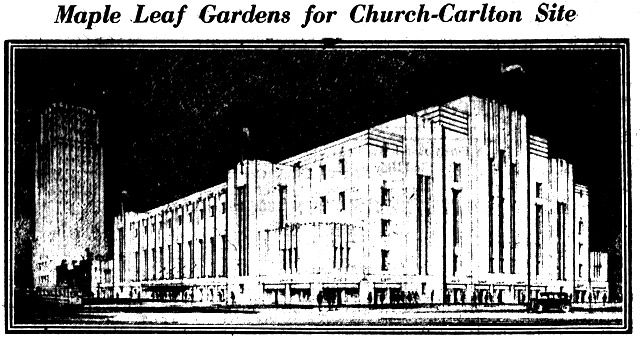

A breakthrough came in January 1931. The Yonge and Fleet site was rejected for good after a $100,000 kickback was demanded by a party involved in the sale. Eaton’s decided to sell the Carlton and Church site, though it maintained the right to approve the exterior design of the arena. This would not prove a problem as the architectural firm hired, Ross and Macdonald, had also designed Eaton’s College Street. Eaton’s would also receive $25,000 worth of stock.

Beyond the clout of fellow Maple Leafs directors such as mining executive J.P. Bickell in calling in favours with other businessmen, Smythe used all of his powers of persuasion to convince others to invest in the new arena. As Trent Frayne described him in a 1999 Globe and Mail profile:

Smythe wasn’t a big fellow, but he could dominate a room. His bright blue eyes were his most revealing physical aspect—warm and welcoming sometimes, colder than ice cubes other times. He was often intimidating, as often charming. He was described once by a friend as a “practical mystic. He believed in playing hunches and he believed in luck; mix his superstitions with his practical ability and you had him, a belligerent Irishman.” He was stocky and big-chested. He wore pearl grey spats and an off-white Borsalino fedora. He could be somewhat acerbic.

Smythe, Bickell, and the other executives prodded local business titans to invest, despite questions about the timing of building a $1.5 million facility. As Elias Rogers Coal head Alf Rogers asked Bickell, “Don’t you know there’s a depression on?” (Rogers eventually bought twenty-five thousand dollars worth of stock).

Maple Leaf Gardens Ltd. was incorporated on February 24, 1931. Its prospectus promised potential investors that as few as five shares “would make you as enthusiastic a fan as the wealthiest subscriber.” Gardens shares were touted as excellent gifts and positioned as a way to build a financial trust for children.

When construction bids were tendered, the Gardens found itself $250,000 short of financing the lowest offer. When Smythe came out of a meeting with the Gardens board and bankers indicating that they felt construction should be delayed for a year, Maple Leafs business manager Frank Selke ran down to an Allied Building Trades Council meeting on Church Street. Selke, who also served gratis as the business manager of an electrician’s union, proposed to the attending unions that any labourers who worked on the Gardens would receive 20% of their pay in Gardens stock instead of cash. Few objections were raised toward Selke’s scheme and he proceeded to sign agreements with twenty-four unions. When word of this plan reached Sir John Aird of the Bank of Commerce, he agreed to fund any lingering shortfalls. Workers who held onto their shares would have eventually made a nice little profit, as prices fluctuated from the fifty-cent range in the mid-1930s to the hundred dollar level by the end of World War II.

Construction began on June 1, 1931 and proceeded at a rapid pace. Haste was necessary, as the facility had to be ready for the Maple Leafs home opener on November 12. Over 1,200 labourers, 750,000 bricks, and 77,500 bags of concrete were required to build the Gardens. The cornerstone was laid by Ontario Lieutenant-Governor W.D. Ross in a dignitary-laden ceremony on September 21. “Toronto,” said Ross, “is, and has been for years, a sports centre. Our position on Lake Ontario, our National Exhibition, our general enthusiasm for sports of all kinds — amateur and professional — make this city the ‘logical location’ for a building worthy of our record, of cur[rent] need and of our ambition.”

Bickell then stated the aims and idealism behind the Gardens, as well as complimenting Ross. We don’t recall some of the following aspirations being trotted out when the Air Canada Centre came to be, nor did the name W.D. Ross roll off the tongues of Leafs fans.

This building, with which I trust your name will be long associated, perhaps might be regarded as a civic institution, rather than a commercial venture, because its object is to foster and promote the healthy recreation of the people of this British and sport-loving city. It represents the combined efforts of all sections of the community. Capital for its creation has come very largely from those who are actuated by a spirit of civic patriotism, rather than a desire to reap financial benefit. No less a high ideal has inspired those who labo[u]r is creating it, for I am glad to tell your Hono[u]r that the members of the various trades employed are becoming part-owners of the enterprise by accepting a substantial portion of their remuneration in stock. There is I believe no precedent in any similar project for this happy situation.

A time capsule was laid that day, which was opened 80 years later.

Long lines formed when season tickets went on sale on October 14. Selke and Smythe dropped by the queue to observe the buyers. Selke related to Globe columnist Bert Perry the specific seating needs of one family, who were fans of Leafs tough guy Red Horner:

One subscriber was telling the ticket-seller that he wanted tickets for his wife, his daughter and himself. He mentioned that his daughter, a high school student, was a great hockey fan, and she was particularly fond of the playing of Red Horner, the youthful defense player of the Leafs. It was his desire to obtain seats that would be located as near to Horner as it was possible to get during a game, so he finally decided to take them right behind the penalty box. And that is where he got them.

Despite minor delays, the Gardens was ready to greet a sold-out crowd of over thirteen thousand eager to see the Leafs take on the Chicago Black Hawks on opening night. Early in the day, Smythe wandered from line to line to observe the reactions of those seeking rush tickets. His queue jumping drew the notice of a police officer, who escorted Smythe off the premises until his identity was established. A later starting time was planned so that patrons had enough time to acquaint themselves with the seating plan.

The Black Hawks were in a state of disarray when they came to Toronto. Despite having reached the Stanley Cup final a few months earlier, coach Dick Irvin either quit or was fired in September. This wasn’t a shocking move given owner Frederic McLaughlin‘s habit of going through coaches like one changes clothes. “Where hockey was concerned,” Smythe once mused, “Major McLaughlin was the strangest bird and, yes, perhaps the biggest nut I met in my life.” McLaughlin’s wife, dancer Irene Castle, felt he ran the Black Hawks “with the zeal of an amateur who doesn’t know what it’s all about.”

Godfrey Matheson was hired as Irvin’s replacement and guided the team through pre-season training in Pittsburgh. He failed to arrive in Toronto. While initial reports suggested he was hospitalized for a stomach ailment, the Telegram reported on opening day that Matheson had “departed to Florida, a victim of a nervous breakdown.” The paper suspected that McLaughlin might “forget his pride” and rehire Irvin. Instead, it appears team physical director Emil Iverson went behind the bench.

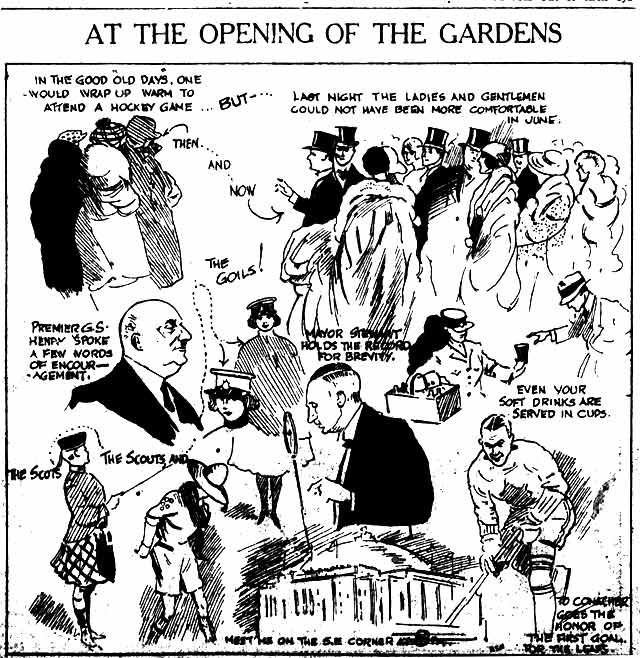

When the 48th Highlanders and Royal Grenadiers band played “Happy Days are Here Again” at 8:30 p.m., Smythe felt that “the scene was pretty much as I had imagined it in my rosiest dreams.” After the bands finished, Mayor William J. Stewart presented the team with floral horseshoes on behalf on the city. The many dignitaries who followed bored sections of the crowd. Telegram columnist Ted Reeve joked that “the ceremonies included everything but a one minute silence as a tribute to the stockholders.” Several paper admonished the crowd for heckling the speakers, especially Bickell and Ontario Premier George Henry, demanding that the game begin. In Bickell’s case, according to Selke’s memoir, he “fortified himself with a few extra belts of Scotch” to handle any jeers from the crowd during the long speech he had prepared. “Ceremonies figure out nicely on paper,” Telegram sports editor J.P. Fitzgerald observed, “but they do not work out at all in practice and it looks as though if outstanding citizens are to officiate at openings and on other gala occasions they must confine themselves to pantomimic gestures, short and snappy, a kind of lending their visible presence only.” Mail and Empire sports editor Edwin Allan echoed these sentiments, noting that “there will be no more opening ceremonies in professional games this year, and this is something to be thankful for.”

As for the audience in general, Perry observed:

With its row upon row of eager-eyed enthusiasts rising up and up from the red leather cushions of the box and rail seats, where society was well represented by patrons in evening dress, through section after section of bright blue seats to the green and grey of the top tiers, the spectacle presented was magnificent. The immensity of this hippodrome of hockey, claimed to be the last word in buildings of its kind, was impressed upon the spectator, and those present fully agreed that Toronto had at last blossomed forth into major league ranks to the fullest extent.

The structure may have awed attendees, but the on-ice product didn’t. Mush March of the Black Hawks scored the first goal early in the first period. The Leafs tied the score late in the second period thanks to Charlie Conacher, but fell behind for good when Vic Ripley scored early in the third period. The Leafs outshot the Black Hawks 51-35 but the sterling goaltending of Chuck Gardiner helped Chicago come out on top by a score of 2-1. Gardiner’s performance was remarkable given the game was stopped for fifteen minutes during the second period when Conacher collided with the goalie (during this time, NHL teams rarely carried a backup). Though Gardiner’s arm was severely injured, he made it back on the ice and was applauded by the crowd.

One spectator who didn’t have a good opening night was Forest Hill resident Norman Martin. During the game, three youths stole his car. “Up in the labyrinths of Rosedale,” the Mail and Empire reported, “Motorcycle Officer Constable #263 saw them and decided they looked suspicious. He chased them and ran their car into the curb. As they stopped, one of the trio hopped out of the car and hot-footed into the night.” All three were charged with car theft and hauled into juvenile court the next day.

After a slow start and a coaching change that saw opening night coach Art Duncan dumped after five winless games in favour of Irvin, the Leafs also proved to be a success by the end of the 1931/32 season, when they brought the Stanley Cup to their new home.

Sources: Maple Leaf Gardens: Fifty Years of History by Stan Obodiac (Toronto: Van Nostrand Reinhold Ltd, 1981); If You Can’t Beat ‘Em in the Alley by Conn Smythe with Scott Young (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1981); J.P. Bickell by Jason Wilson, Kevin Shea, and Graham MacLachlan (Toronto: Dundurn, 2017); The Lives of Conn Smythe by Kelly McParland (Toronto: Fenn/McClelland & Stewart, 2011); The Story of Maple Leaf Gardens by Lance Hornby (Champaign: Sports Publishing Inc., 1998); and the following newspapers: the September 22, 1931, October 15, 1931, and November 13, 1931 editions of the Globe; the February 13, 1999, and February 17, 1999 editions of the Globe and Mail; the November 11, 1931, November 12, 1931, and November 13, 1931 editions of the Mail and Empire; the November 12, 1931 and November 13, 1931 editions of the Telegram; and the November 13, 1931 edition of the Toronto Star.