By Thomas van Laake, University of Manchester, Léa Ravensbergen, McMaster University, David Simor, The Centre for Active Transportation, and Matti Siemiatycki, University of Toronto

Cycling is booming on the shores of Lake Ontario. Plans and policy objectives seeking to promote urban cycling, once considered a fringe initiative limited to pre-amalgamation “Old Toronto,” are now common practice for municipalities across the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA), from Burlington to Durham and beyond.

Despite the adoption of Vision Zero, Net Zero, and cycling network projections, however, the realities of cycling practice and infrastructural conditions in large swathes of the GTHA remain sobering. It could be argued that the gap between policy goals and real-world implementation has never been wider. As municipalities struggle to achieve the transformative change necessary to mainstream cycling as a transport mode, the limitations of existing frameworks and best practices are becoming increasingly apparent.

In a virtual seminar held on the 5th of October, The Centre for Active Transportation (TCAT), the Infrastructure Institute at the University of Toronto, and the School of Earth, Environment & Society at McMaster University invited a diverse group of professionals, academics, and activists working to improve urban cycling in different GTHA contexts to reflect on the pathways and prospects of cycling promotion across the region. In this recap, we present an overview of the themes discussed during the event, which featured three sessions that can be rewatched on TCAT’s YouTube channel: on suburban infrastructure, data collection and pilot projects, and the pursuit of equitable cycling.

Thinking cycling beyond downtown

In taking a GTHA-wide approach to cycling, the seminar explicitly sought to look beyond central Toronto and Hamilton. While infrastructure in those downtown areas has improved considerably over recent years, the suburban built form that characterizes most of the region poses a different set of challenges.

Nancy Smith Lea, Senior Advisor and co-founder of TCAT, recalled that Toronto’s first bike plan was adopted in 1996, two years prior to the city being amalgamated with five surrounding municipalities that were more suburban in character and more car dependent. “At the time, cycling plans were largely considered downtown plans,” she emphasized. In contrast, “today, cycling plans and road safety plans have been developed across the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA) in all types of urban forms – urban, suburban and rural.” Notwithstanding the adoption of plans and policies, suburbs pose a “chicken or egg problem” for cycling advocates: the car-centric urban form and hostile infrastructure pose a significant barrier to those seeking to go about their daily activities by bike, and where few dare to cycle, it is harder to make the case for safe infrastructure.

In the session on suburban infrastructure, the discussants agreed that different approaches to cycling promotion and infrastructure development are required. However, the emphasis of the strategies varied. Andre Sorensen, Professor of Geography at the University of Toronto, laid out a vision for an off-road network in Scarborough, which could take advantage of under-utilized land along hydro corridors and creeks to provide critical connections for cyclists, as well as spaces for recreation. Compared to the politically difficult challenge of rebuilding roads and streets, this network represents “low hanging fruit.” Nonetheless, Sorensen conceded that infrastructure alone is not enough to comprehensively boost cycling in a place like Scarborough.

Active travel advocates TCAT have long recognized that culture and sociability is key, and since 2014 have sought to stimulate cycling by launching community bike hubs in several different communities in the Toronto region, in Peel, Scarborough, Markham and most recently Newmarket. Marvin Macaraig, Scarborough Cycles Bike Hub Coordinator, explained their strategy of “incubating” suburban cycling, detailing the ecosystem of social and human supports that most new cyclists rely on to grow confidence. For Marvin, the expansion of infrastructures like Bike Share Toronto in areas that lack both safe conditions and supportive programming is more likely to leave people feeling excluded. The overarching message is that a multi-pronged and context-sensitive approach is necessary, rather than simply replicating the same infrastructures in very different contexts.

How does cycling relate to urban (re)development?

Across the seminar’s sessions, a consensus emerged that the potential for better cycling improvements in the GTHA depends on how urban (re)development is managed. With the region slated to add millions of new inhabitants over the coming decades, could urban development and intensification be leveraged to facilitate cycling? Or will development pressures end up entrenching suburban sprawl while pricing potential cyclists out of centrally located and bikeable neighbourhoods?

Thinking through the implications of ongoing and projected urban redevelopment along Scarborough’s major arterial roads, Professor Sorensen stressed that it “is really essential to make sure that [cycling infrastructure] goes in advance of all this new intensification [..] so that developers can make connections [to] the network.” On the other hand, municipalities should be wary of overly relying on development contributions to fund cycling infrastructure, suggested Becca Mayers, Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Waterloo: “much of the cycle network is determined by the decision to develop or not develop an area. [This funding] can only be used in the location itself rather than going to a pool fund to equitably distribute infrastructure.” The negative effects of the piecemeal development of infrastructures are perhaps most evident in Toronto’s protected bike parking, which sees access to fancy facilities at new transit stops managed cumbersomely by city bureaucrats, rather than a dedicated agency. Here, there is considerable potential for Toronto’s transit expansion to better integrate with cycling improvements and further improve accessibility for those without access to a car.

Of course, most of the GTHA lacks higher-order transit and is more likely to see further sprawl rather than intensification. The smaller and intermediate municipalities across the GTHA can look to the experience of nearby Kitchener-Waterloo. Brian Doucet, Associate Professor in the School of Planning at the University of Waterloo, highlighted the role of the LRT in stimulating a rethinking of transportation priorities, and reflected on how smaller municipalities have “fewer degrees of separation” between advocates and decision makers. Presenting some examples of new cycling infrastructure in Kitchener-Waterloo, he finds that “some of the best [cycling] infrastructure [..] is actually in new neighbourhoods built out on the edges of the city.” Indeed, this holds true across the GTHA, where municipalities such as Ajax and Milton have quietly built considerable cycling networks. However, it remains very challenging to comprehensively mainstream cycling in low-density areas criss-crossed by dangerous arterial roads.

Data is political

Cycling projects have long garnered scrutiny in Toronto, culminating in the 2016 Bloor Street pilot, which was accompanied by independent studies of economic impact and road safety, in addition to the city-led review of traffic impacts. These studies have expanded the increasingly broad “evidence base” on the benefits of cycling and the need for protected infrastructure. Indeed, with these numbers in hand, the implementation of projects and programs to support cycling may seem straightforward. Not in the GTHA, where calls for “more studies” or “better data” continue to characterize conflicts around the redesign of roadways. For instance, Keep Toronto Moving, an anti-bike lane pressure group, has demanded that Toronto adopt a “data-driven” approach to cycling, suggesting that the city does not collect the right information.

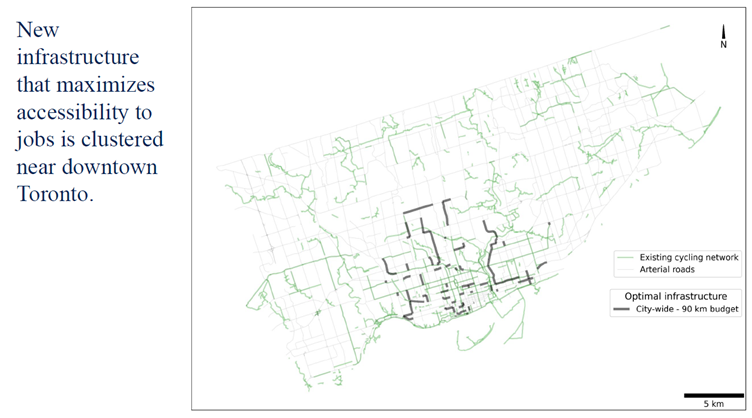

Taking a firmly pro-bicycle stance, Madeleine Bonsma-Fisher, a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Toronto, exhibited how a more advanced transportation data analysis can help inform planning. Her research, which maps the accessibility benefits of infrastructure according to their impact on “level-of-traffic-stress” connectivity, could help the city evaluate the equity and effectiveness of new cycling connections. However, she insisted that there is no “optimal” way to expand the cycling network, and hard choices need to be made in terms of how to distribute improvements across the region. In addition to better analysis tools, this will require an understanding of how to actually get projects done – both politically and practically. In this sense, data and models will never substitute for a well-coordinated and capable institutional apparatus.

Moreover, there are always limitations to data. Not everything is measurable, nor easily comparable. Time passes and conditions change, especially during the pandemic years. The city must make choices about what kinds of data to collect, and how to evaluate these outcomes. For instance, trips under one kilometre distance are often not counted in travel surveys. This leads to an overemphasis of the trip to work and overlooks care trips, underlined Léa Ravensbergen, Assistant Professor at McMaster University. On the other hand, a gender-sensitive approach can help overcome limitations in data collection: the rate of female cyclists has been used as a “proxy” for subjective perceptions of safety. Where more women cycle, the reasoning goes, conditions must be relatively safe. However, Adam Hasham, Senior Advisor at Metrolinx, pointed out that there is no one-size-fits-all strategy to data collection. Each project poses a different set of conditions and problems. Contradicting the perception of data as “neutral” information, Toronto’s recurring controversies over what data to collect, how to collect it, and how this data can inform policymaking, make it clear that the interpretation of the “facts” will always be context-specific and politically contested.

Infrastructure pilots need rethinking

In the GTHA, many cycling projects pass through extensive “pilots” – a practice considerably expanded during the Covid-19 pandemic. In theory, pilots enable staff to test and evaluate projects before scaling up and making them permanent, but they also open the door to deferral, delay, and entrenched opposition. Although pilots have become common practice and the succession of studies that have accompanied them has helped build “the evidence base,” Adam Hasham and Zarah Monfaredi, a PhD student researching Canadian cities” pandemic-era cycling improvements, agreed that they remain very much “ad-hoc.” Adopting a more “standardized process and plan” to cycling network expansions could accelerate improvements and avoid inflating conflict, they agreed. For Adam, this means articulating infrastructure projects with well-established policy goals – reducing emissions, improving safety and health, connecting the network – and “moving from a plan that [focuses on] what do we want to build, to why do we want to build it?”

Across the sessions, discussion turned to the difficulties of fair and balanced consultation processes. Adam Hasham lamented that “at every pilot […] we let the loudest people decide what we value as a city.” Meanwhile, those who stand most to benefit from safe infrastructure, such as food delivery workers, are often overlooked. For Becca Mayers, it is crucial to actively seek out a multitude of voices, using “a variety of engagement techniques” on the ground, such as intercept surveys and en-route feedback from users of pilot projects. Equally, the shift to online consultations during the pandemic provided an opportunity to address unbalanced representation, with Zarah Monfaredi suggesting that “young [mothers] can now be talking about their support for bike planes while breastfeeding.” However, there’s also lessons to be learned about what NOT to do. The consultation processes during the pandemic were often rushed. The consultations for the Brimley Road bike lanes, which were soon removed after installation, were “the definition of how not to do consultation,” and “sowed distrust” among the local community, argues Marvin Macaraig, who is closely involved in advocacy in the Southwest Scarborough area. In future occasions, “it is very important to allow residents to provide feedback ahead of project implementation rather than [..] implement first and collect feedback second.”

Cycling is an equity issue

Reflecting an increasing commitment to achieving equitable transportation, speakers across all sessions reflected on how inequalities in cycling rates and conditions continue to differentiate population groups and areas across the GTHA. Though cycling is a very affordable transport mode, which is relied on by many low-income and unhoused GTHA residents, many still associate it with a “downtown elite.” The concentration of cycling facilities in downtown areas has reinforced this perception. However, as city centres have gentrified, poverty has become increasingly concentrated in car-dependent suburbs. Accordingly, Madeleine Bonsma-Fisher suggests that “when we’re thinking about […] equity and accessibility, we shouldn’t [prioritize] giving more access [by bike] to people that already have such high access,” but rather focus on those “marginalized groups on the outskirts of the city that […] tend to have worse accessibility by cycling then areas downtown.”

A wider reconsideration of what kinds of projects are most important may be necessary, suggests Léa Ravensbergen. She emphasized that the significant gender gap in cycling rates in the GTHA, where over two-thirds of cyclists are men, “is not natural. [It] does not have to be normal. And this is something that we can and should change.” For too long, cycling infrastructure planning has emphasized the trip to work. “That’s and important trip […] but do remember care trips. [That’s] not just grocery stores […] that’s dropping kids off at school, that’s hospitals.” Many of these trips are short, and could be done by bike, but the devil is in the details. Providing safe bike parking is critical, especially for family-friendly e-bikes. And even where safe infrastructure is provided on public roads, the final stretch to arrive at destinations is often across a dangerous parking lot.

Certainly, there remain many cultural, as well as physical, barriers to cycling fully entering the “mainstream” as a normal and everyday transport mode. What most people can agree on, however, is that children across the GTHA should be able safely travel to school by foot or cycle. For Kojo Damptey, an instructor at McMaster University and Hamilton community organizer, an inclusive approach to cycling would prioritize all children living in “healthy active neighbourhoods.” Positioning cycling improvements as a means to an end, rather than an end in its own right, Becca Mayers argued that equitable cycling can foster “more inclusive, egalitarian societies.” With this goal in mind, cycling advocates should also reflect on how the process of change can be made more inclusive as well, suggested Zarah Monfaredi. In addition to ensuring an equitable distribution of the benefits of cycling policies, she called for more attention to “recognitional equity,” foregrounding the perceptions, motivations, and identities of local residents and their active participation in planning processes.

Looking towards the future

Though many of the political setbacks and reverses to cycling policies over the past decades seem to have been overcome, successfully promoting cycling in the GTHA remains a difficult task. While better infrastructure continues to be essential to developing the potential of bicycles to provide cheap, flexible, and healthy travel, the seminar’s discussions often turned to the importance of narrative and storytelling. For Brian Doucet, cities can improve their communication around cycling, getting the information out there and making residents feel included in decision making. However, the most effective work will be within communities themselves, done by advocates and organisers such as Kojo Damptey, who is in close contact with local schools to promote safe travel to school in Hamilton, or Marvin Macaraig’s work with cycling programming in Scarborough. Such efforts build local constituencies for cycling, raising the pressure on councilmembers and enabling planners.

In this sense, favourable social and cultural conditions, rather than infrastructure alone, will be critical to mainstreaming cycling across the GTHA. Though it was not discussed in the seminar, policymakers and advocates alike would also benefit from reflecting on the role of bike-transit integration, wayfinding, and upcoming technologies such as electric bikes, in enabling cycling in suburban areas. Such future-oriented infrastructural policies could be leveraged to overcome barriers to long distance cycling, as well as cycling through winter. Equally, considerable potential exists for new technologies and techniques to contribute to improved data collection, analysis for planning, and community outreach. Nonetheless, the seminar’s discussions made clear that the comprehensive transformations of infrastructures and mobility practices necessary to achieve the GTHA’s modal shift, emissions reduction, and road safety targets will remain contested and circumscribed for the foreseeable future.