Olivia Chow’s victory in the Toronto mayoral by-election, brushing off anti-bike lane rhetoric, has been hailed as a new dawn for cycling in Canada’s largest city. Perhaps even more significantly, the previous 2022 municipal election had consolidated a pro-cycling majority on city council, including many supportive councillors in suburban wards. In the wake of these electoral successes, the new mayor has claimed that “bike lanes are not actually controversial at city hall”, suggesting that Toronto may finally have added the missing ingredient to its cycling policy: political will.

Is the alignment of a pro-cycling council and mayor in Toronto an opportunity to dramatically expand the provision of safe cycling infrastructure, something alike Paris under Anne Hidalgo? While outside observers may be optimistic, close followers of Toronto’s municipal politics, and local cyclists (particularly those in the suburbs) are likely to be more skeptical.

During my recent study visit to Toronto, part of a PhD project on cycling infrastructure policy, I dedicated myself to learning more about both these topics, by studying the municipal decision-making process regarding cycling infrastructure, as well as exploring large swathes of Toronto’s outer wards by bicycle. In this post, I will set out reasons why it may be difficult for Mayor Chow to reshape the city in her image, and outline some considerations for more effective city-wide transformation.

Plans, procedures, and funds

Mayor Chow heads a city with a considerable institutional apparatus for cycling, with capable staff and ambitious policies and targets in place. While progress was often slow, developments were generally positive under the previous mayor, John Tory. Nonetheless, the city consistently failed to meet its own cycling network targets. It would be easy to attribute this to Tory’s lukewarm attitude to bike lanes. However, delivering new cycling facilities can be a drawn-out and contested process, particularly if space for motorized vehicles is affected. Here, Toronto’s system of close democratic oversight of changes to road layouts, in which most cycling projects must be approved by city council not once, but twice, and can effectively be vetoed by the local councillor, presents a significant barrier to rapid and transformative change.

There are also practical and financial reasons for the city’s plodding pace. Many cycling improvements are packaged with road reconstruction and surface transit projects, enabling planners to maintain general traffic lanes and parking – and thereby avoid opposition. Nonetheless, opportunities to redesign entire rights of way are increasingly limited, as the city’s budget crunch reduces the portfolio of road reconstruction projects. Equally, the problems affecting transit projects such as the Eglinton LRT end up delaying cycling network delivery as well. Limited staff capacity and a range of bureaucratic obstacles ranging from environmental assessments to inflexible utility infrastructure also help explain the incremental and creeping character of cycling network expansion in Toronto.

Under these conditions, the ability of a Chow administration to dramatically scale up street interventions is limited. Any such move would require more funding to expand staffing and capital budgets. This could be achieved by freeing up resources allocated to the wasteful Gardiner rebuild or by generating new funding sources, both politically controversial moves. Not all potential changes involve additional expense, however. City council could free up staff time by delegating authority to carry out projects more efficiently, building on precedent set during the pandemic response. Similarly, the adoption of more temporary road closures, from reinstating ActiveTO to copying Montreal’s successful summer streets, could expand cycling provision with little capital expense.

Geography, equity, and integration

Clearly, under the new mayor, Toronto’s cycling policy will keep moving forward, is even likely to be sped up. But it is at least as important to consider where and how to expand cycling infrastructure, as not all projects are equally useful, nor difficult.

Toronto’s Long Term Cycling Network Vision stipulates that nearly every major arterial will get a bicycle facility at some point – the question is when, and how. The siting and sequencing of projects is determined in near-term implementation plans, with planning staff currently identifying targets for 2024-2027 – a detailed balancing act that goes far beyond setting a kilometre target. Should the city focus on consolidating the downtown grid, or shift emphasis to the as yet underserved suburbs? Is it more important to deliver higher quality facilities, such as protected intersections, or to rapidly expand the network using quick-build methods? What proportion of staff time and funds should be dedicated to improving existing bike lanes, rather than building new ones? As city staff ponder these difficult dilemmas, often on a case-by-case basis, Mayor Chow has a unique opportunity to give form to the planned bike network expansion during her tenure. Investment in underserved areas, already an important consideration in infrastructure planning, is likely to be further emphasized. The difficulty lies in passing from discourse to implementation.

In terms of designs, the major challenge lies in how to improve cycling along Toronto’s major arterial roads. Rather than focus on interventions targeted (and marketed) as exclusively for cyclists, the city has begun to emphasize integrated changes in a ‘complete streets’ model. In the ideal scenario, these would include high-quality bike lanes, but these are not always feasible – or necessary. On suburban arterials with relatively low cycling demand, upgrading sidewalks to multi-use trails could provide a good alternative that improves pedestrian conditions as well. Another ‘integrated’ solution currently being rolled out city-wide are the RapidTO bus priority corridors, which are designated as shared spaces for bicycles. While sharing lanes with buses may not be appealing to many cyclists, such facilities still represent a major improvement on the status quo and are a win-win for bikes and transit.

More broadly, however, bike-transit integration is a weak point for Toronto, which hampers efforts to promote cycling in outlying neighborhoods. While more garages and lockers are being installed (for instance, as part of the Eglinton Crosstown), the cumbersome and costly process to access them poses a barrier to more widespread use. A more effective model for managing these facilities could draw on the example of how the Parking Authority has run Bike Share Toronto, but overcoming the TTC and Metrolinx’s manifest disinterest in bicycle parking will require significant work – and monetary resources.

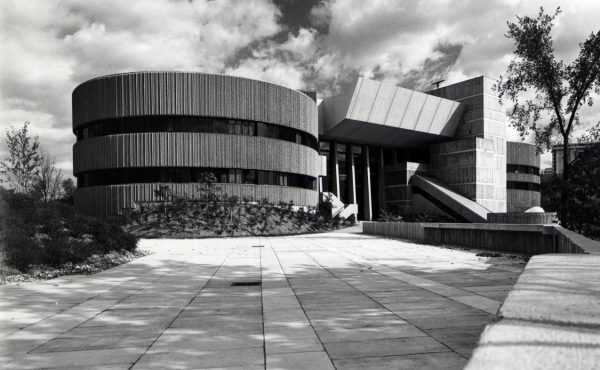

Getting the institutional arrangements right is critical to the implementation and operation of particular types of infrastructure, as well as to the long-term success of cycling policies. However, the 2019 reorganization of Toronto Transportation Services (TTS), which sought to integrate cycling considerations in all transportation policy and infrastructure decisions made by the city, has not been a wholesale success. There is a risk that “cycling improvement” becomes reduced to the presence of a bike lane, while business-as-usual traffic planning is continued. While seeking to maintain traffic lanes is understandable along lower-density, outlying corridors, it is less justifiable in areas well-served by transit and undergoing intensification, such as Six Points (see image above). Toronto’s aspiration to become an equitable cycling city hinge on whether policies and infrastructures address the relationships between land-use, mobility practices, and road design holistically, rather than formulaically.

With the political and institutional levers in place at the city level, this process of change could benefit from a geographically targeted approach. While the differences between the downtown core and the suburbs may be obvious, neither are homogeneous. On closer consideration, Toronto’s inner suburbs are diverse not only ethnically, but also spatially. Some areas, such as around Eglinton East, could benefit from easily accessible cycle parking along their new transit facilities, particularly if Scarborough’s multi-use trail network is strategically expanded. Where RapidTO corridors are implemented, the route choice of cyclists and their interactions with buses will have to be monitored to evaluate longer-term improvements. Along the municipal border, better connections to surrounding GTA municipalities make a lot of sense (for instance, across Steele Avenue). And while the extension of the Bloor Street West bike lane has been closely watched by many, the impacts of the concurrent expansion of Bike Share Toronto, bike parking, and the cycling network around York University and the Jane and Finch area may be more critical to Toronto’s long-term network vision.

What does a successful cycling policy look like in Toronto?

Neither Olivia Chow’s mayoralty, nor the city’s cycling team, should be evaluated only on the basis of how many kilometers of bike lanes are delivered. Facing financial and practical limitations, Chow’s ability to accelerate change is limited, despite council support. In the short term at least, it will be best to keep the current process moving forward, discreetly overcoming any political obstacles that may appear.

Chow’s true challenge could be reconstrued as not just executing the network plan, but rather setting in motion and facilitating processes of pro-cycling change across the city, particularly in the suburbs.

With much of the “low hanging fruit” in and around the downtown area already in place, the mayor and her staff must make difficult choices regarding which types of projects to prioritize and how to give form to a city-wide network.

I would argue for a flexible and spatially targeted strategy. Rather than replicate designs city-wide, the city would be better off responding to the differential needs and trajectories of neighborhoods. A more inclusive cycling environment will look very different in the suburbs than in downtown.

Segregated, exclusive spaces for bicycles will remain important, particularly on the most dangerous roads, but they are only one element of a much wider puzzle. Regulatory measures such as speed limit reductions and the banning of right-turn-on-red could be expanded to complement physical changes to streets. Future-oriented reflection on the diverse uses and users of cycling facilities and their broad range of vehicles, from wheelchairs and to an ever-wider range of electric micromobility vehicles, could also help foreground more inclusive design solutions. More broadly, the extension of the cycling network beyond the downtown core will require fostering and supporting the social infrastructures of cycling, from local workshops to community cycling hubs.

As Toronto rebuilds its roads, expands its transit system, and densifies neighborhoods, opportunities to improve and leverage cycling are continually arising. Whether the city can take advantage will depend on a more integrated, and geographically targeted, approach to cycling infrastructure delivery. Will Mayor Chow have the vision?

Photos by Thomas van Laake

Thomas van Laake is a PhD student at the University of Manchester, interested in the differences and similarities of cycling infrastructure policies and practices in cities around the world.

2 comments

To be fair Mr Van Laake, I wouldn’t really call the 6 Points intersection re-design as fully car centric if he knew the former spaghetti junction of overpasses that existed before (though maybe he does). Sure, it could have been better, but folks were fighting for years to get a level intersection where people could actually walk and bike (I should know as I grew up a few blocks from there). If anything it is far more pedestrian friendly then what it was for the past 40 – 50 years. Additonally, we can expect to see the Bloor bike line connected to 6 Points early next year and the possible building of bike lanes along Dundas when the new BRT is built. When we create the Kipling and Martin Grove bike paths I think it will be a huge difference (the sooner the better).

Thanks for this, and your broader observations via Manchester at some point. Yes, we may now have the political will in place, 22 years after the 2001 Bike Plan, which also went a bit beyond mere infrastructures, but even cheap paint wasn’t possible, especially in the outer suburbs like Scarborough. And it’s not merely political will within Toronto that should be for road safety, not merely bike infra: the Province of Ontario has multiple levers, sometimes on the hidden side, that ensure both meddling and muddling. Even the federal level has a set of roles: one scourge of current core bike lanes is the degree of faster e-bikes, but Mr. Harper’s regime OK’d what in Europe would likely be in a firm need license and NOT in bike lane category.

We still aren’t thinking of better biking as a public health measure, which it is, and often have ‘mywardopic’ ‘vision’, and I’m glad Ms. Bailao isn’t our Mayor despite some clear strengths, but beyond badly needed Bloor bike lanes through the underpasses, she let some things languish or not happen. Eg. College St. bike lanes from Brock to Lansdowne in that 2001 Bike Plan.

And Parkdale!

A key gap in our network is longer east-west safe trips, and on main direct routes, so the core citizens can choose mobility and bikes can compete with the TTC, (which the City/TTC isn’t wanting to let happen, becau$e…). The crash stats through the decades do show consistent harm and death on Queen W., (and King, Dundas, College, and Bloor), and they’re not counting streetcar track harms usually, though bodies hard to miss.

It’d be a big ticket item to move the Queen tracks north about a meter, and create space on north side for a proper separated lane from c. Ossington over to Brock, and it’s unique in its possibility as the streetcar network only links to Queen on the south side at Shaw and Dufferin, so north-side corners will be intact from no turnings. (Yes, the Queen subway as per 1957 plan would make road repainting easy like Bloor was, eventually). After 20-odd years of risk and death, this is overdue for fixing, despite cost and more real stress for the area from a construction process, but the Roads department does feel to be firmly in control as the Queensway rebuild should have had bike safety within it, but nothing, so Parkdalians can remain isolated and caged out of High Park, but Etobicoke has good bike lanes on Queensway to High Park….

Perhaps 8 years ago there was a City-led mapping by colour of bike harms by core area and outer burbs, and in the fine print it was observed in a twisted way that there was a diminishing of the worth of a core cyclist so it took two core cyclists to one suburban one for the colourations. Vigilance! – and having a fuller only-separated-lanes-are-safe stance may ensure the ice caps are well melted ahead of any full network, and we also have to trim our concrete usages.