Over a three-day weekend last winter, the last few residents of the retirement home at the west end of our street were quietly moved out. No one really saw them leave—there weren’t any telltale moving vans—and it took a while to realize that the building was now locked and empty, unlit, with a few rolled-up flyers rustling around on the entrance steps. Not long after, early on a Sunday, chainsaws and bucket loaders took down all the trees, and as soon as the weather turned warm, demolition teams arrived. With impressive skill they tore the structure apart and carted it away. Walking around the site after they finished, I couldn’t spot a single brick.

Completed in 1946, the building had a functional, shoebox shape that served the community well, first as an apartment complex, later as assisted living. Neither beautiful nor ugly, it seemed congruent with the neighborhood and was always well-maintained; for years, people went there to vote. I never thought to photograph it, but now it’s hard to remember exactly what it looked like. I had to use Google Street View to verify how far it was set back from the sidewalk, and where each of the trees had once stood. And the replacement building’s website, which promises much but reveals little, seems expressly designed to blur out whatever impressions of the original might still linger in the mind’s eye.

Taken together, these overlapping strategies—camouflaged tenant displacement, stealth tree removal, fencing off the craters where buildings once stood, papering up sales offices with airbrushed graphics—serve to evidence a conviction that induced amnesia is a good thing, and that the shortest pathway to acceptance of the new leads directly away from any reference to the past.

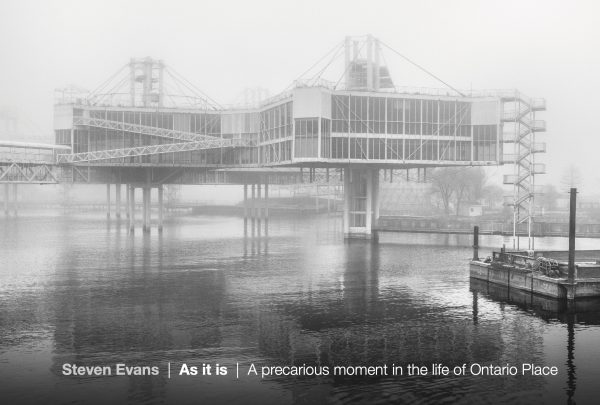

All of these issues—place, memory, the illusionist logic of urban renewal, well-functioning neighborhoods under siege from development—were already on my mind when Steven Evans’ new book, As it is: A precarious moment in the life of Ontario Place, was released. The book startled me, not just by virtue of how good it was, but also by how quickly it tripped the reset button on my idealized and complacent mental image bank. Within minutes, I was toggling back and forth between sections of the book and postings on the Ontario Place for All website. The neglect was worse than I realized, the future less determinate than I wanted to think, and more alarming still, the shared general belief that this extraordinary part of the Toronto waterfront would always be public property—more grounded in nostalgia than any current reality—was facing a serious and immediate challenge.

In the book’s preface, Evans outlined the circumstances that led him back to Ontario Place, what he found there, the ways in which his photography had developed over time, and how the project took form. His introduction is followed by two essays: John Lorinc’s outstanding account of the history of Ontario Place [editor’s disclosure: John Lorinc is a senior editor at Spacing], and Maia-Mari Sutnik’s probing discussion of Evans’ photographic work and the context in which it can be best understood. The entire volume is divided into six sections, each with a brief descriptive introduction, also by Evans. Serving in effect as chapters, these offer a visual walking tour of many features of the two islands: the Cinesphere and Pods, the West Island, the Wilderness Adventure Ride, the shoreline and breakwaters bounding the West Island, the East Island, and Trillium Park.

In contrast to the doublespeak about Ontario Place now pouring out from the wellsprings of provincial bureaucracy, the texts in As it is are clear, succinct and informative; there isn’t an extra word anywhere. And the photographic sequences are equally well-crafted. There’s a good reason for this: the book evolved through twenty-eight iterations before being finalized, during which time Evans worked intensively with curator David Harris and editor Beth Kapusta. Available online are John Lorinc’s interview with Evans about the project, and two very fine reviews, by Aria Novosedlik for Applied Arts (October 2023) and by Adele Weder for Azure Magazine (November 2023). I recommend them: for days I tried to write something as good, but had no success.

Eventually I came to realize that Evans’ entire project could be appreciated more fully as a document than as a polemic, and that its documentary value would remain regardless of what might transpire at Ontario Place in the near term. Extended consideration of the photographs themselves—compelling visual records of landforms that should, somehow, manage to outlast the present struggles over who will control them—led me to think there were aspects of Evans’ picture-making that deserved consideration on their own terms: most particularly, his attention to light, framing, perspective, and effective utilization of the black and white tone scale. Lastly, I began to see that his work could also be appreciated in relation to some photographers not necessarily associated with the main traditions of documentary picture-making.

The light changes as you approach the shore of Lake Ontario: there is more of it, you can see further, the horizon is a constant presence, the reflecting water is never still. In humid or overcast conditions, this light can seem to literally fill up your eyes; when the sun is out, it can reach right into your body. The vastness of the lake and sky, and the aliveness of light and weather, is something to contend with. Some photographers end up changing contrast or adjusting the density of the sky to better suit their expressive goals; but Photoshop or no, many who try this cannot achieve any sense of realism. In these images, however, Evans seems to have lifted out the luminance from the landscape in front of him, held it briefly in his camera, and directly transposed it onto the printed page. Very few photographers can do this, but you can see this kind of attention to light in Paul Strand’s work from the Outer Hebrides, or, more recently, in Robert Adams’ images made along the Pacific coast. Hiroshi Sugimoto, although he photographed light and water in an utterly different way, is the only other photographer I can think of who has this same degree of control over the gray scale while photographing at water’s edge.

Throughout the book, interesting rhythms and cross-rhythms animate the forms within each frame. While the photographs are all horizontal, for the most part leading the eye across from left to right and upward from foreground to background, it is Evans’ use of vertical accents that binds together the geometry of each composition. Evans worked for decades as an architectural photographer, and he told me that he became completely comfortable previsualizing his images on a view camera ground glass, where they would appear upside down and backwards. “I learned quickly,” he said, “that if the verticals were right, the image would work,” and this has been a feature of his work ever since. One of the earliest of Evans’ projects that I studied in detail was Making Room (1983), a series of construction photographs of The Atrium on Bay: I’d never seen complex formal arrangements rendered with such logic and clarity, and I often wondered if Evans had another, secret life as a mathematician. Whether or not this is true, it’s interesting to consider.

While both Evans himself and Maia-Mari Sutnik refer to the New Topographics movement in relation to Evans’ approach, I’ve always found a certain coolness and detachment in that work—and, as often as not, visible threads of irony or critique. But Evans’ photographs, especially those in this volume, are not ironic. Rather, they are vibrant, sharp-edged, formally resolved, and well-placed on the page. They are also, despite their urgency in relation to the threats posed to Ontario Place and despite their lightness and transparency, elegiac; I don’t see irony anywhere. The photographer Minor White liked to say that a good photograph was “both lyrical and accurate,” and that holds true for Evans to a far greater degree than for those associated with the New Topographics. I’d go so far as to say that of all the influences he mentions, Evans is closer to Atget than anyone else, despite the many differences in their situations and working methods.

Thinking more about the horizontal framing, the frequent presence of the horizon itself, and Evans’ use of wide-angle lenses (significantly wider than those used by Walker Evans, who was also mentioned as an influence by both Evans and Maia-Mari Sutnik), I was eventually led to the wide-field work of Art Sinsabaugh and Josef Koudelka, who used panoramic cameras to wonderful effect. Sinsabaugh’s Midwest Landscapes resonate deeply with Evans’ work, as do Josef Koudelka’s projects from The Black Triangle in the Czech Republic and his Industrial Landscapes.

“… [T]he photographer starts with the frame,” wrote John Szarkowski in The Photographer’s Eye. “The photograph’s edge defines content … the frame is the beginning of a picture’s geometry.” While it was an entirely different world when Szarkowski wrote this—I hadn’t opened this book in years and was amazed to see it cost $6.95—the accuracy of this simple observation still holds. And everything about Evans’ images, and about his new book, represents an exercise in good framing. The content is detailed and accessible: nothing is glossed over or hidden, nothing is idealized, mis-stated or obscured. The texts are thoughtful and full of information, but comprehensible to anyone; and the photographs are consistently well-seen and beautifully rendered. It took a while to grasp the book in its entirety, and to see past the frame of mind in which I initially approached it. But now As it is sitting on my desk rather than a bookshelf; and, however the future of Ontario Place gets decided, I hope it wins a prize.

All photographs by Steven Evans.

Cross-posted from Don Snyder’s website. Don Snyder is a Professor Emeritus at the School of Image Arts at Toronto Metropolitan University and has served twice as department Chair.

An exhibition of Steven Evans’s Ontario Place photography is on at the Urbanspace Gallery, 401 Richmond St. W., until Saturday April 20, 2024.