Cheryl Thompson is a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Black Expressive Culture & Creativity, Associate Professor of Performance at Toronto Metropolitan University.

It’s Black History Month and this year feels different. Across the U.S., as led by Donald Trump’s campaign to erase “inconvenient” histories, Black History Month events are being cancelled or scaled down, including at major retailers, technology companies, and government agencies. Black-owned companies and entrepreneurs have even had to publicly urge against a boycott, especially at big box stores.

The political rhetoric — on both sides of the border — has turned equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI or DEI in the U.S.) into coded racial language, as happened previously to terms like “woke,” and CRT (critical race theory). Such campaigns aim to devalue any attempts to create a more just society. Of course, any program of change is going to have its critics, and many people have critiqued EDI, including myself. Critique is healthy; unsubstantiated mistruths are not. As Canadian equity consultant Camille Dundas has said, clawing back EDI does not mean that the real issues — of under-representation, discrimination, and the glass ceiling of inequity — disappear. When we eliminate EDI efforts, those issues simply go unaddressed.

With both the provincial and federal levels of government busy focused on politics this month, the spotlight on Black histories feels dimmed. However, Black social media has continued sharing stories that would otherwise go unnoticed.

While researching this article, for example, I learned about Gloria Baylis through social media posts. Author and entrepreneur Akilah Newton’s YouTube channel, Canadian Encyclopedia, and lawyer Lavinia Latham’s LinkedIn article all profile her story. Baylis, who had immigrated to Canada from Barbados, applied in 1964 for a nursing aide position in Montreal, but was told the position was filled (her White friend was encouraged to apply). With support from the Negro Citizenship Association, Baylis sued the establishment under Quebec’s newly enacted Act Respecting Discrimination in Employment (1964), which made her case the first racial discrimination workplace lawsuit in Canada.

The Negro Citizenship Association (NCA) was founded in 1951 by Donald Willard Moore (1891–1994) to pursue social and humanitarian reform. Its motto was, “Dedicated to the promotion of a better Canadian citizen.” Moore, also born in Barbados, worked as a sleeping car porter on the Canadian Pacific Railway in Montreal. After relocating to Toronto, he became a major figure in Canadian civil rights, including leading the 1954 delegation that saw NCA representatives, as well as unions, labour councils, and community organizations go to Ottawa to demand changes to immigration policy.

When I was a kid, my Jamaican parents would share stories about friends and their own experiences with workplace and immigration discrimination. There are no records for what these people went through, only the stories told to us from that generation. In school, I did not learn about figures like Moore or Baylis. Rather, their stories reached me via social media posts and online blogs during Black History Month.

Black people in Canada have experienced profound exclusion, discrimination, and racism, not only in the past, but as ongoing realities in healthcare, leadership positions at our colleges and universities, in the business world, and across the creative industries. But we have also demonstrated resilience and a determination to succeed, and part of that resolve comes from sharing Black histories.

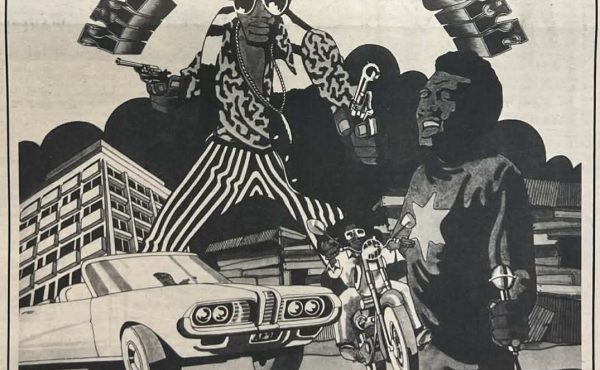

For Black History Month 2025, I have delved into the history of segregated nightclubs in Toronto. If you’ve never heard about nightclub segregation, it started in the 1930s and continued through the 1960s and 1970s. It is not a remote history.

Segregated nightclubs on Lakeshore Boulevard

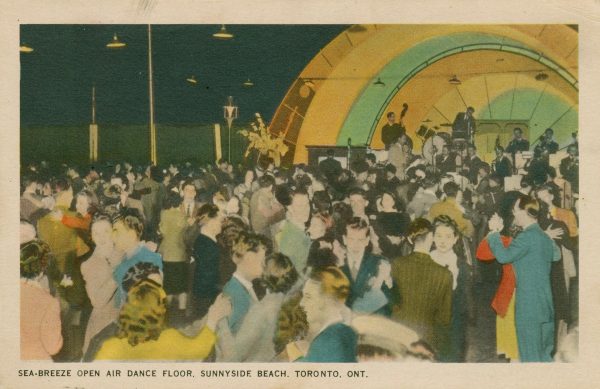

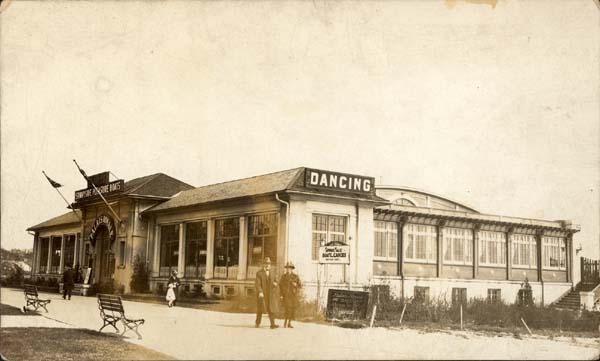

Most of Toronto’s nightclubs were originally jazz establishments, and later they became rhythm and blues and soul music venues. Lakeshore Boulevard was the primary location for nightclubs with dance floors. Built in 1932, The Seabreeze was an outdoor 2,000 sq-m dance pavilion located at Sunnyside Amusement Park, just east of the pool. The Club Esquire, which changed its name to Club Top Hat, was located nearby; by 1940, it was one of the most popular dance clubs in the Sunnyside area. The Silver Slipper, renamed Club Kingsway, and which later became a bingo hall, was another Lakeshore jazz nightclub. All of these clubs were segregated.

As the late researcher and musician Wade Pfaff once observed: “During the Great Depression in Canada, there were no federal laws dictating racial segregation. But right up to the end of the Second World War, local customs and regional business practices ensured that there were very few premier performance venues in Central and Eastern Canada that allowed Black Canadian artists, much less Black customers.”

Black musicians who broke the colour-barrier

Cy McLean and His Orchestra was the first Canadian all-Black band to regularly perform at segregated dance floor venues like Club Top Hat. According to Canada’s Black Music Archives, McLean was born in Sydney, Nova Scotia, in 1916. In addition to being a bandleader, he was a pianist who worked from the 1940s until the 1970s. In 1947, McLean and his band were the first all-Black band to open at the Colonial Tavern, a Yonge Street club that had a record of barring Black musicians from performing there.

The Ontario Jewish Archives holds the record of Barrie, Ont.,-born singer Phyllis Marshall, who, between 1943 and 1944, became one of the first Black singers to have a residency at Toronto’s Park Plaza Hotel. She first appeared at the Silver Slipper in 1938, alongside the Canadian Ambassadors, Canada’s first organized Black jazz band, which was founded by Niagara Falls-born Myron Pierman “Mynie” Sutton.

Dancing at nightclubs

By the late 1940s, Toronto was home to several jazz nightclubs, from the Fairmont Royal York’s Imperial Room to the Town Tavern on Queen Street East. The Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) Tent, the Palace Pier, and Palais Royale were, however, the most popular jazz dancing venues. Opened in 1938, the CNE Tent, located just inside the Prince’s Gates, had an open-air dance floor.

As an advertisement from a CNE Official Catalogue and Programme in 1940 declared:

“Dancing! Dancing — in the great, airy pavilion on a satin-smooth floor. Dancing — to the world’s finest dance bands. Dancing — toe-tickling tunes by music-making masters of rhythm ‘sweet’ and ‘swing.’ Dancing — to the bands you’ve dreamed of, now a reality in the Dance Pavilion.”

Opened in the 1920s, The Palace Pier was another spot where all the famous acts played, as described in Peter Young’s book about Ontario’s dance halls and summer pavilions. They included stars of the big-band era, from Duke Ellington to the Dorsey Brothers and Lionel Hampton. Finally, the Palais Royale was the crown jewel of these nightclubs. Built in 1922 (and still here today), it operated as a ballroom/concert hall and was a favourite spot for Count Basie & His Orchestra, who played there well into the 1960s.

Source: City of Toronto Archives, Series 330, File 567 Public Domain

Dancing around the colour-line

In her work on social dancing, University of Toronto dance professor Seika Boye found (see her 2018 exhibition, It’s About Time: Dancing Black in Canada 1900-1970) that while it was illegal to reject patrons on the basis of race or religion, Toronto venues employed other means of controlling who patronized their clubs, such as enforcing codes of conduct.

For example, the Seabreeze had signs in the 1940s that warned patrons before purchasing tickets to “behave themselves on the dance floor — jitterbugging and fast dancing were prohibited here.” Such signs were racist because jitterbugging (like Lindy hopping) was a social dance derived from Black American culture and community (watch Black dancers talk about Lindy hopping at Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom). By posting signs barring the jitterbug, these nightclubs were not only restricting Black patrons but also integrated dancing.

By the early 1940s, Toronto’s Black community started protesting these discriminatory practices. The Palais Royale was at the centre of several cases in 1942 and 1947 regarding its segregation practices. Similarly, in 1945, after Don Jubas and Harry Gairey Jr. were refused entry to the skating rink Icelandia, they took their case to the media, and eventually, to public officials who changed the laws. (Jamie Bradburn’s Tales of Toronto blog gives a detailed account of this case).

In 1954, Ontario’s Fair Accommodation Practices Act (FAPA) was passed; it was the first piece of legislation that specified that it was against the law to “deny any person or class of persons the accommodation, services or facilities available in any place to which the public is customarily admitted because of the race, creed, colour, nationality, ancestry or place of origin.” While this law meant the removal of signs with coded language, discrimination continued into the 1950s.

By the 1960s, all nightclubs on the Lakeshore, except the Palace Pier and Palais Royale, had been demolished to make room for the Gardiner Expressway, which opened in 1956. With that change, the history of anti-Black racism in these venues was erased from the public consciousness. Today, you can find photographs of these nightclubs in their prime, but only disparate mentions of their anti-Black policies and staunchly enforced segregated dance floors.

The only reason I am writing this article is because I, too, had no clue about this history until I came across a post on Instagram in 2023. I located the photograph in the post on the TPL Digital Archive, and did some digging to find the original Toronto Daily Star article from August 2, 1963 which accompanied the image. Only then did I learn more about the story of Gloria Simpson.

“She Beat bias”

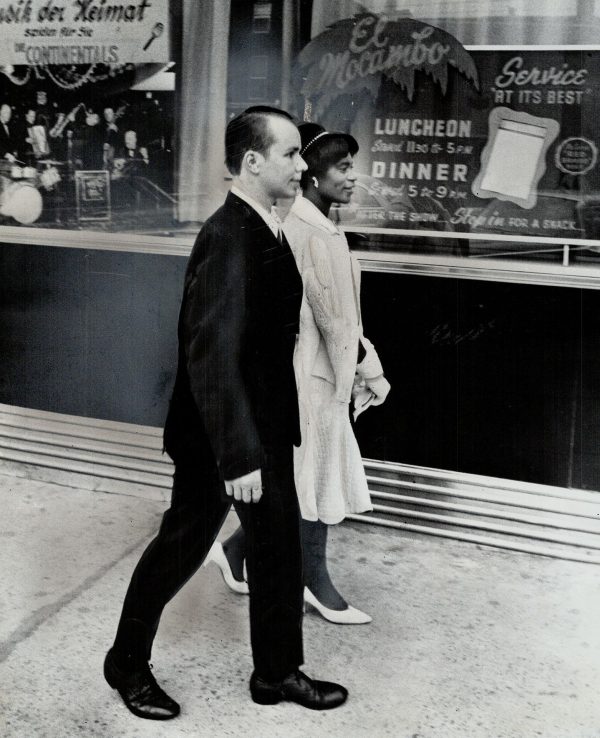

The short Daily Star editorial titled, “She Beat Bias,” presented Simpson’s photograph alongside the caption:

“Gloria Simpson of Markham St., Jamaican assistant nurse, approaches El Mocambo tavern on Spadina Ave. last night with friend Peter Ziegler after winning civil rights case. In March she was barred at door of Deutches [sic] Tanz Lokal dance club on second floor of tavern. Yesterday Ontario Human Rights Commission [OHRC] settled case and management invited her to return.”

Deutsches Tanz Lokal was a German dance club that rented the second floor of The El Mocambo at some point in the 1960s. While we associate the club’s iconic neon palm tree sign with the 1977 Rolling Stones concert and live recording, it actually opened in 1946. The El Mocambo was originally a Latin-themed live music club with dining on the main floor and a dance hall occupying the second floor. It was also the first bar in Toronto to receive a liquor licence when the Ontario liquor board loosened its control over alcohol in 1947.

When I submitted a Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) request to find out more about that OHRC case, Gloria Simpson v. Deutsches Tanz Lokal, the file came back almost completely redacted, other than confirmation that she had won her case against Tanz Lokal. I do not know Simpson’s story nor how her case reached the media. But in recent years, the story of “Little Jamaica” has been documented, as well as that of the Harriet Tubman Youth Centre on St. Clair West, and the UNIA on College Street. We know Black people found ways to gather and build community at night, despite racism; the archival record of Toronto-born jazz legend Archie Alleyne (1933–2015) is living proof of that.

Like so many other groups who have endured discrimination, we share these stories, especially during Black History Month, to heal. This is the restorative work that must reside at the heart of equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts, so that we never forget that Black life is much more than an acronym. It’s about the innumerable stories of life, joy, and community, many of which have yet to be told.

Cheryl Thompson is a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Black Expressive Culture & Creativity, Associate Professor of Performance at Toronto Metropolitan University. She is also author of Uncle: Race, Nostalgia and the Politics of Loyalty (2021), and Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture (2019, and can be reached on BlueSky @drcherylt.bsky.social