What has recently been dubbed the “Sunlight” mural hung on the facade of the spray-drying tower at the historic Lever Brothers* Don Valley plant for total of 36 years, including the 14 years between its final shutdown and its demolition in 2023.

The mural was commissioned by the company in 1987 to mark the hundredth anniversary of the introduction of Sunlight Soap in Canada, which led to the opening in 1901 of the original Canadian Sunlight Soap Works at this location. Although it borrows industrial iconography, the mural’s soft colour palette evokes the artisanal origins of soap making rather than its modern identity as heavy industry.

In 1987, when he was chosen to create the mural, artist Phillip Woolf was an assembly line worker at the plant. He had refined his painting skills while participating in an educational leave program offered by the company. After his stint at Lever Brothers, he became a well-known art teacher at Seneca College and completed other mural commissions in Welland and Toronto.

In dry detergent manufacturing, the spray-drying tower is a tall, cylindrical stove used to convert a liquid spray into detergent powder. A colossal new spray tower had been added to the Don Valley plant in 1983, adding a bold vertical element to its main facade.

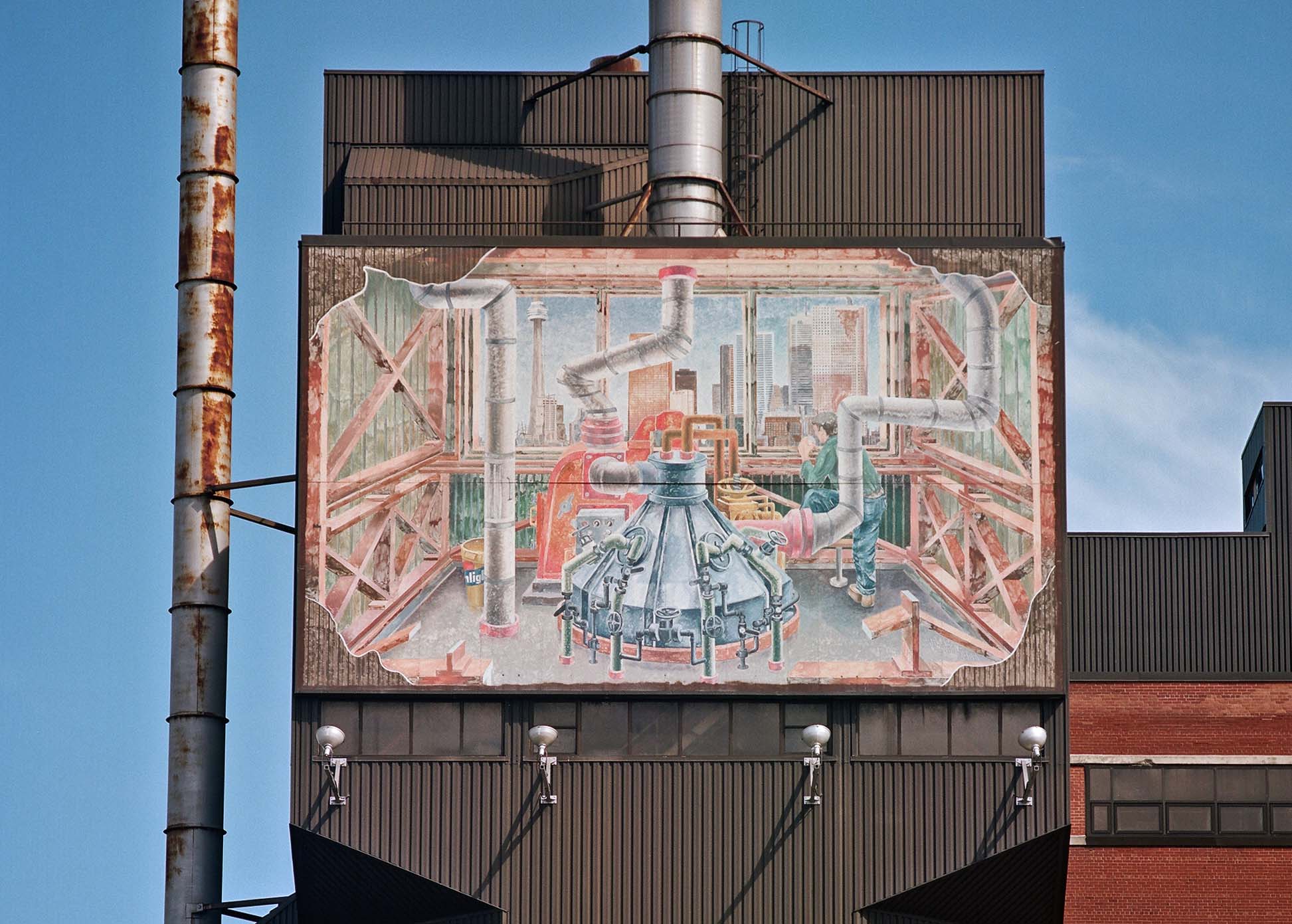

For his mural, Woolf chose to offer the public a view into the interior of an imaginary mechanical room at the very top of the tower. To reinforce the impression of a cutaway view, Woolf used several ingenious framing devices. At first glance, the composition presents itself as an irregular cartouche attached directly to the vertical metal cladding of the spray tower. Closer inspection reveals that the areas of wall at the four corners are actually painted in trompe-l’oeil on the flat panel.

Inside the cartouche, the wall structure of the room has been surgically cut away to give us a wide-angle view of the interior. The steel-framed side walls lead the eye to a central picture window. A worker with his back to the viewer is taking a coffee break as he looks out at the Toronto skyline. But our own view is interrupted by a trio of kinked exhaust pipes, one of which seems to pass through the frame and connects visually with the real exhaust stack behind it.

Valuable information about the project can be gleaned from a CFTO Night Beat News item from 1988. It includes an interview with the artist and footage showing the panels of the mural being installed “like pieces of a giant jigsaw puzzle.” We are informed that Woolf painted the original on canvas, and that it was then “blown up and painted onto a weather resistant material.” However, the fate of the original canvas and actual process used to enlarge it remain unknown.

Some specifics can be gleaned from a recent CBC News report by Michael Smee, dealing with the uncertain future of this public artwork. We learn that it is composed of 24 panels of uniform dimensions. My 2015 photograph (above) shows that they are arranged in two horizontal rows. The assembled mural would appear to have an overall size of about 32 by 48 feet. It’s not possible to learn anything more because the developer of the former Lever Brothers site, Cadillac Fairview, won’t reveal the artwork’s location or its condition.

Phillip Woolf wasn’t the only artist-employee whose work was featured at the Don Valley plant while it was still active. In 2003, I photographed a giant, stylized portrait painted by Bill Salinas on the wall outside the employee training room. I recall that there were also hand-painted images of Lever Brothers products displayed in the main stairwell. All were erased after the plant closed and the developer First Gulf purchased the site.

Now that Cadillac Fairview has demolished every structure of the Lever Brothers factory complex, the Sunlight Mural is the only resource left with which to recognize this site as part of Toronto’s social and industrial history. However, in Michael Smee CBC report, several concerned persons are suggesting that other sites might be suitable for displaying it.

Although well-intentioned, such suggestions tend to deflect attention away from Cadillac Fairview’s responsibility to restore this major work of public art to its original location. It was created as a site-specific work, and should remain so.

Local city councillor Paula Fletcher and the Toronto and East York Community Preservation Panel should have paid attention to this matter much earlier, but it’s not too late to get it right.

* The Lever Brothers brand name survived in Canada after the formation of the Unilever multinational corporation in 1929.

All photos © P. MacCallum (petermaccallum.com)