This second part of my feature on Lever Brothers soap and detergent manufacturing in the lower Don Valley will examine the eight-decade history of Plant No. 1, known as the Sunlight Soap Works within its local industrial context, before returning for a second look at the surviving Plant No. 2 through the eyes of the distinguished architectural photographer, Steven Evans.

Plant No. 1 opened in 1900 on a wedge-shaped site bordered by the Don River on the west, Eastern Avenue on the north and the curving Grand Trunk rail corridor on the southeast. The construction of the rail corridor in 1866 had been the first step in the industrialization of the area, followed by the straightening of the Don river channel in 1888 and the construction of the first Eastern Avenue bridge across the Don in 1900.

By 1900 the lower Don was already a heavily industrialized district where the air was full of noxious odours and the sun was often viewed through a haze of coal smoke. A measure of the enthusiasm generated by the appearance of the Sunlight Soap Works in this blighted neighbourhood is that its closest neighbour, the storied Toronto Baseball Ground, was promptly renamed Sunlight Park. Remarkably, although the baseball ground closed in 1913, its name lived on as a designation for the soap works itself.

The new Sunlight Soap Works received adulatory reviews in the press for being the largest soap works in North America, for its rational production process, and for its new, odourless soap-making technology, which used glycerin and vegetable oils rather than tallow (see transcripts from The Toronto Evening Star and The Montreal Gazette (PDF)).

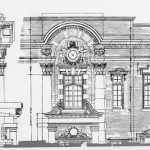

The architectural design of the new factory complex contributed to its favourable reception. The Sunlight works was the first project completed by the newly formed partnership of Sproatt and Rolph, whose later designs included Hart House at the University of Toronto, the Royal York Hotel and the Canada Life Building.

While the production of Sunlight bar soap in Plant No. 1 was highly automated, packaging of the bars in cardboard cases required “two rows of nimble fingered girls.” At its founding in 1885, Lever Brothers had introduced a new model for labour relations which, although paternalistic, was said to be of benefit to its mostly female workforce.

Since the electrical grid was then in its infancy, the plant generated its own power. A 250-horsepower steam engine drove a locally manufactured 125-kilowatt generator. Contemporary journalists noted approvingly that this power source allowed the company to provide its employees with hot lunches cooked by electricity.

In the early 1900s, Lever Brothers would have offered industrial workers healthier working conditions than did its immediate neighbours, which included the Consumers Gas Station B to the east, the Frankel Brothers scrap metal smelter to the north, and, directly opposite on the west bank of the Don, the Wickett and Craig Tannery and the huge William Davies pork packing plant.

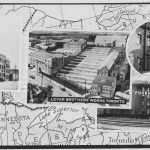

Notable early additions to the Sunlight complex included the North and South buildings of 1920, designed by the architect J. F. Sparling. Both were three-storey concrete loft building of the “daylight factory” type, featuring enormous windows. After 1950, a group of conduits that dipped under the rail viaduct allowed steam and process liquids to pass between the soap works and Plant No. 2.

By 1965, the original Sproatt and Rolph office building at Plant No. 1, with its off-centre Neo-Baroque entrance portal, had been replaced by the Lever Brothers Technical Centre, a modernist slab designed by Mathers and Haldenby whose curtain wall mimicked that of Lever House, the Company’s prestige office tower in New York.

Although the original Lever Brothers plant survived until 1988, its former site is now a warren of car dealerships. In 2004, the former Technical Centre was transformed by Quadrangle Architects into a BMW showroom, attracting the attention of southbound drivers on the Don Valley Parkway.

The image sequence below includes views of early transportation infrastructure in the lower Don Valley. The most important element remains the rail corridor established in 1856 for the Grand Trunk Railroad. Between 1925 and 1934, the ground-level tracks were replaced by the waterfront viaduct that is still in use, and whose location will influence the placement of the East Harbour station on the Ontario subway line.

Not all the industries that surrounded the Sunlight soap works in the twentieth century were photographed in detail, but most appear in municipal aerial survey photos taken between 1947 and 1992.

The Wickett and Craig Tannery on Cypress Street operated continuously from 1891 to 1990. Its site is now buried under the flood protection berm of the Corktown Common.

The Consumers Gas Station B manufactured gas plant opened in 1912 and closed in the mid-1950s. Three distinctive buildings from this complex have survived along Eastern Avenue, but it has also left behind 40 years worth of heavy soil contamination.

Frankel Brothers moved to the north-east corner of Eastern Avenue and Don Roadway about 1910. It supplied the structural steel for the construction of Lever Brothers Plant No. 2. Its property was expropriated in 1962 to make way for a ramp connecting the new Eastern Avenue flyover to the Don Valley Parkway.

The Lever Brothers Plant No. 2 and the nearby Hearn Generating Station were designed and built by the engineering firm of Stone and Webster, opening within a few months of each other. Although the names of the architects have not yet come to light, both structures represent the modernist factory aesthetic that was practiced by Toronto’s most prominent firms during the post-war period.

The lower Don Valley is one of the most important places in Toronto for retaining a link to our city’s often gritty industrial past by preserving historic structures and adapting them to new uses. As my colleague Steven Evans’ photos show, the surviving architecture of Lever Brothers Plant No. 2 is a powerful representation of its time and place.

See more images relating to the Sunlight Soap works, from the Leslieville Historical Society.

Acknowledgments

The following persons contributed to my research for this article: Adam Birrell, Rebekah Bedard, Michele Dale, Lisa Doherty, Joanne Doucette, Dave Durette, Steven Evans, Gerald Hitchcock, Yoonhee Lee, Helen Unsworth

Copyright Notice

Images 3, 6-8, 16, 18-20 © Lever Brothers Archives

Images 24, 25, 28-31 © P. MacCallum

Images 33-44 © Steven Evans

1. Illustration from “A Visit to the Sunlight Soap Works, Toronto.” The Gazette, Montreal, April 5, 1902.

1. Illustration from “A Visit to the Sunlight Soap Works, Toronto.” The Gazette, Montreal, April 5, 1902.

2. Detail of elevation and section for entrance portal, Sunlight Soap Works. Canadian Architect and Builder, March, 1900. Sproatt and Rolph, Architects.

2. Detail of elevation and section for entrance portal, Sunlight Soap Works. Canadian Architect and Builder, March, 1900. Sproatt and Rolph, Architects.

3. View of office entrance portal, Sunlight SoapWorks, ca. 1930. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-14, Unidentified Photographer.

3. View of office entrance portal, Sunlight SoapWorks, ca. 1930. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-14, Unidentified Photographer.

4. “Electrical equipment for the Sunlight Soap Works.” Electrical News and Engineering Journal, February, 1901. Engineering and Computer Science Library, University of Toronto.

4. “Electrical equipment for the Sunlight Soap Works.” Electrical News and Engineering Journal, February, 1901. Engineering and Computer Science Library, University of Toronto.

5. Lever Brothers Soap Works, making boxes, 1919. City of

Toronto Archives, Series 372_Sub-Series 41_Item 534, Arthur Goss.

Taken for the Ontario Safety League to illustrate the importance of machinery guards in industrial plants.

5. Lever Brothers Soap Works, making boxes, 1919. City of

Toronto Archives, Series 372_Sub-Series 41_Item 534, Arthur Goss.

Taken for the Ontario Safety League to illustrate the importance of machinery guards in industrial plants.

6. New South Building, Sunlight Soap Works, August, 1920. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-12, Unidentified Photographer. Note: glaziers installing panes from inside the third floor.

6. New South Building, Sunlight Soap Works, August, 1920. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-12, Unidentified Photographer. Note: glaziers installing panes from inside the third floor.

7. Untitled promotional photo montage showing Lever Brothers’ Canadian operations, ca. 1925. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-12

The Sunlight works is illustrated, with the new North and South buildings in place. The photo on the lower right shows the Pugsley Dingman Comfort Soap works in West Toronto Junction.

7. Untitled promotional photo montage showing Lever Brothers’ Canadian operations, ca. 1925. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-12

The Sunlight works is illustrated, with the new North and South buildings in place. The photo on the lower right shows the Pugsley Dingman Comfort Soap works in West Toronto Junction.

8. LB Ltd Toronto Factory general view taken from opposite side eastern level ca. 1925. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-12, Unidentified Photographer.

View from an upper floor of Frankel Brothers warehouse.

8. LB Ltd Toronto Factory general view taken from opposite side eastern level ca. 1925. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-12, Unidentified Photographer.

View from an upper floor of Frankel Brothers warehouse.

9. Harbour Industrial Railway, October, 1917. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1231_Item 212, Arthur Goss. The Sunlight works is visible on the left. Behind the walking figure is the Grand Trunk rail bridge across the Don.

9. Harbour Industrial Railway, October, 1917. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1231_Item 212, Arthur Goss. The Sunlight works is visible on the left. Behind the walking figure is the Grand Trunk rail bridge across the Don.

10. Eastern Ave. at the Don, E.S. Looking West, Nov., 1925. City of Toronto Archives, Series 372_Sub Series 84_Item 525, Arthur Goss. The first Eastern Avenue bridge opened in 1900. A second bridge was built beside it to carry Consumers Gas mains.

10. Eastern Ave. at the Don, E.S. Looking West, Nov., 1925. City of Toronto Archives, Series 372_Sub Series 84_Item 525, Arthur Goss. The first Eastern Avenue bridge opened in 1900. A second bridge was built beside it to carry Consumers Gas mains.

11. Eastern Ave. Gas Coy Bridge, July, 1929. City of Toronto Archives, Series 372_Sub Series 84_Item 555, Arthur Goss. The Sunlight works appears on the left. The collapsed Consumers Gas bridge was replaced by the concrete structure that remains in use today.

11. Eastern Ave. Gas Coy Bridge, July, 1929. City of Toronto Archives, Series 372_Sub Series 84_Item 555, Arthur Goss. The Sunlight works appears on the left. The collapsed Consumers Gas bridge was replaced by the concrete structure that remains in use today.

12. Don River Bridge form the N. W., July, 1926. Fonds 1231_Item 1959, Arthur Goss. The original Grand Trunk Railway truss bridge dating from 1856 was flanked by two lighter bridges.

12. Don River Bridge form the N. W., July, 1926. Fonds 1231_Item 1959, Arthur Goss. The original Grand Trunk Railway truss bridge dating from 1856 was flanked by two lighter bridges.

13. Trestle East From Cherry. May, 1927. City of Toronto Archives, Series 372_Sub Series 79_Item 222, Arthur Goss.

13. Trestle East From Cherry. May, 1927. City of Toronto Archives, Series 372_Sub Series 79_Item 222, Arthur Goss.

14. Don Bridge West Abutment, January 1926. City of Toronto Archives, Series 372_Sub Series 79_Item 24, Arthur Goss. The abutment shown under construction here supports the high-level bridge that carries the waterfront rail viaduct across the Don.

14. Don Bridge West Abutment, January 1926. City of Toronto Archives, Series 372_Sub Series 79_Item 24, Arthur Goss. The abutment shown under construction here supports the high-level bridge that carries the waterfront rail viaduct across the Don.

15. West of Eastern Filling Trestle, Jan., 1927. City of Toronto Archives, Series 372_Sub Series 79_Item 179, Arthur Goss. The Sunlight works can be glimpsed through the open trestle.

15. West of Eastern Filling Trestle, Jan., 1927. City of Toronto Archives, Series 372_Sub Series 79_Item 179, Arthur Goss. The Sunlight works can be glimpsed through the open trestle.

16. Aerial view of Sunlight works from southeast, ca. 1932. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-11, Unidentified Photographer. The new rail viaduct is visible in the lower left corner. On the left middle, the abandoned GTR rail bridge. Part of the William Davies plant appears on the upper left corner. On the top left side, the east facades of the Wickett and Craig tannery. The three-truss Eastern Avenue road bridge shown here opened in 1933 and was abandoned in 1964.

16. Aerial view of Sunlight works from southeast, ca. 1932. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-11, Unidentified Photographer. The new rail viaduct is visible in the lower left corner. On the left middle, the abandoned GTR rail bridge. Part of the William Davies plant appears on the upper left corner. On the top left side, the east facades of the Wickett and Craig tannery. The three-truss Eastern Avenue road bridge shown here opened in 1933 and was abandoned in 1964.

17. Aerial view of Sunlight works from northwest, August, 1953. Archives of Ontario, C 30-1-0-3399, Northway Gestalt Corporation. The Frankel Brothers scrapyard and smelter are visible in the lower left corner, along with Consumers Gas Station B in the upper left and the Imperial Oil tank farm in the upper right corner.

17. Aerial view of Sunlight works from northwest, August, 1953. Archives of Ontario, C 30-1-0-3399, Northway Gestalt Corporation. The Frankel Brothers scrapyard and smelter are visible in the lower left corner, along with Consumers Gas Station B in the upper left and the Imperial Oil tank farm in the upper right corner.

18. Lever Brothers Toronto, extreme left Exec and general office, centre engineering office maintenance, extreme right works office and labs, ca. 1962. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-14, Unidentified Photographer. Shows the final expanded form of the soap works before the replacement of the main office block. Note the Union Jack, Canada’s national emblem before 1965.

18. Lever Brothers Toronto, extreme left Exec and general office, centre engineering office maintenance, extreme right works office and labs, ca. 1962. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-14, Unidentified Photographer. Shows the final expanded form of the soap works before the replacement of the main office block. Note the Union Jack, Canada’s national emblem before 1965.

19. Toronto Lever House entrance 1960. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-14, Unidentified Photographer.

19. Toronto Lever House entrance 1960. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-14, Unidentified Photographer.

20. Lever Brothers Head Office, Toronto, ca.1968. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-13, Unidentified Photographer.

20. Lever Brothers Head Office, Toronto, ca.1968. Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-13, Unidentified Photographer.

21. Demolition and Alteration to Soapery, August, 1988.

Collection of Dave Durette, Unidentified Photographer.

Shows the boiling pans located on the third floor of the main processing shed.

21. Demolition and Alteration to Soapery, August, 1988.

Collection of Dave Durette, Unidentified Photographer.

Shows the boiling pans located on the third floor of the main processing shed.

22. Former Lever Brothers Head Office re-purposed as BMW showroom, 11 Sunlight Park Road, ca. 2005, Bob Krawczyk. Architectural Conservancy Ontario.

22. Former Lever Brothers Head Office re-purposed as BMW showroom, 11 Sunlight Park Road, ca. 2005, Bob Krawczyk. Architectural Conservancy Ontario.

23. Cypress Street, Looking South, February, 1925. City of Toronto Archives, Salmon Collection No 1198, Arthur Goss. The Wickett and Craig Tannery, seen on the left, occupied the full length of Cypress Street.

23. Cypress Street, Looking South, February, 1925. City of Toronto Archives, Salmon Collection No 1198, Arthur Goss. The Wickett and Craig Tannery, seen on the left, occupied the full length of Cypress Street.

24. Cypress Street, Looking South, September, 1989, Peter MacCallum.

24. Cypress Street, Looking South, September, 1989, Peter MacCallum.

25. The Tan Yard, Wickett and Craig Tannery, Cypress Street, 1989, Peter MacCallum.

25. The Tan Yard, Wickett and Craig Tannery, Cypress Street, 1989, Peter MacCallum.

26. Exterior of Purifying House, Station B, Eastern Avenue, with coal trains from Pennsylvania, 1923. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1034_Item 78, Micklethwaite Studio.

26. Exterior of Purifying House, Station B, Eastern Avenue, with coal trains from Pennsylvania, 1923. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1034_Item 78, Micklethwaite Studio.

27. Interior of Purifying House, showing newly completed purifiers, at Station B, Eastern Avenue, ca., 1923. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1034_Item 778, Micklethwaite Studio.

27. Interior of Purifying House, showing newly completed purifiers, at Station B, Eastern Avenue, ca., 1923. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1034_Item 778, Micklethwaite Studio.

28. Former Consumers Gas purifier buildings, now occupied by City of Toronto offices, 2021, Peter MacCallum.

28. Former Consumers Gas purifier buildings, now occupied by City of Toronto offices, 2021, Peter MacCallum.

29. Looking Southeast from Roof of Lever Brothers Plant No. 2, 2000, Peter MacCallum. The Hearn Generating Station appears on the left.

29. Looking Southeast from Roof of Lever Brothers Plant No. 2, 2000, Peter MacCallum. The Hearn Generating Station appears on the left.

30. Abandoned Hearn Generating Station, view from Joy Oil Site, Unwin Avenue, 2001, Peter MacCallum.

30. Abandoned Hearn Generating Station, view from Joy Oil Site, Unwin Avenue, 2001, Peter MacCallum.

31. Abandoned Turbogenerator, Hearn Generating Station, Unwin Avenue, 2001, Peter MacCallum.

31. Abandoned Turbogenerator, Hearn Generating Station, Unwin Avenue, 2001, Peter MacCallum.

32. Lever Brothers Factory, Toronto, Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-13, Unidentified Photographer.

32. Lever Brothers Factory, Toronto, Lever Brothers Archives, uni-gf-cr-5-24-13, Unidentified Photographer.

33. Finishing Building, view from the southwest, 2017, Steven Evans.

33. Finishing Building, view from the southwest, 2017, Steven Evans.

34. Liquid Filling Line, 3rd floor, Finishing Building, 2017, Steven Evans.

34. Liquid Filling Line, 3rd floor, Finishing Building, 2017, Steven Evans.

35. Spray Tower Discharge, 1st Floor, Finishing Building, 2017, Steven Evans.

35. Spray Tower Discharge, 1st Floor, Finishing Building, 2017, Steven Evans.

36. Detail, maintenance access. To Liquid Storage Tank, 6th Floor, Finishing Building, 2017, Steven Evans.

36. Detail, maintenance access. To Liquid Storage Tank, 6th Floor, Finishing Building, 2017, Steven Evans.

37. Liquid Storage Tanks, 6th Floor, Finishing Building, 2017, Steven Evans.

37. Liquid Storage Tanks, 6th Floor, Finishing Building, 2017, Steven Evans.

38. Scrap Recovery, 4th floor, Finishing Building, 2017, Steven Evans.

38. Scrap Recovery, 4th floor, Finishing Building, 2017, Steven Evans.

39. Liquids Manufacturing Building, view from the southeast, 2017, Steven Evans. This block was also sometimes identified as the Glycerine Building.

39. Liquids Manufacturing Building, view from the southeast, 2017, Steven Evans. This block was also sometimes identified as the Glycerine Building.

40. Main floor, Liquids Manufacturing Building, 2017, Steven Evans.

40. Main floor, Liquids Manufacturing Building, 2017, Steven Evans.

41. Stair leading to tanks, Boiler House, 2017, Steven Evans.

41. Stair leading to tanks, Boiler House, 2017, Steven Evans.

42. Bottom of Coal Discharge Bin, 2nd floor, Boiler House, 2017, Steven Evans.

42. Bottom of Coal Discharge Bin, 2nd floor, Boiler House, 2017, Steven Evans.

43. Coal Bucket Elevator, top floor, Boiler House, 2017, Steven Evans.

43. Coal Bucket Elevator, top floor, Boiler House, 2017, Steven Evans.

44. Boiler House, view from the northwest, 2017, Steven Evans.

44. Boiler House, view from the northwest, 2017, Steven Evans.

45. Detail from Goads Insurance Map, 1924

45. Detail from Goads Insurance Map, 1924

46. Headlines from “A Visit to the Sunlight Soap Works, Toronto.” The Gazette, Montreal, April 5, 1902.

46. Headlines from “A Visit to the Sunlight Soap Works, Toronto.” The Gazette, Montreal, April 5, 1902.

2 comments

Great series on industrial history with photos.

In the summer of 2017, the old Unilever factory became the site of Editdx by Toronto’s Design Exchange. Amongst many others, VTLA Studio (landscape architecture) created an installation for the roof terrace with the theme “No Lot is Vacant”. It featured marginal plants that were harvested by myself and staff of Ecoman Co. (ecological design services) and arranged in a very large and opulent centrepiece illustrating VTLA’s theme. I am a historian by profession and have worked in the field of industrial archeology in Hamburg at the innovative Museum of Work, a living museum, previously.

To add to my previous comment:

The remainder of the roof was turned into an example of urban farming by The Bowery Project via a milkcrate farm (vegetables, herbs, and blooming pollinator plants) installation. At various times, we all were present to talk to visitors, who could relax in groups of patio furniture, about both of these installations. Visitors included many school groups.

We took many snapshots of ours (and other installations throughout the building and the former factory grounds, now marginal zones) during the event and enjoyed enthusiastic feedback and good questions about our ideas and our work.

I did not have time to research the history of the site at the time. So, thank you for filling me and other readers in with your series. Love Spacing magazine.