Recent Auditor General reports exposed deep-rooted inefficiencies and systemic issues in Toronto’s Parks & Recreation (P&R) Division. Despite these challenges, P&R is staffed by many dedicated public servants who understand the problems facing Toronto’s parks and work tirelessly to address them within innumerable constraints.

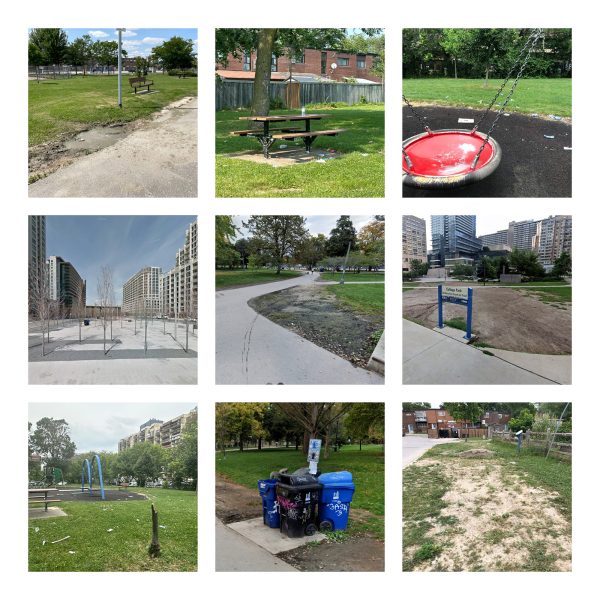

Chronic underfunding, poor oversight, and outdated management have left parks visibly deteriorating—broken benches, dead trees, and neglected playgrounds are common. The pandemic and a lack of supportive housing further strained the system, turning parks into shelters for unhoused residents. Meanwhile, absurdly restrictive rules—such as bans on tobogganing, limits on gatherings, or ball games—alienate users and limit engagement.

Toronto has over 1,500 parks, many built decades ago, often without a designer on record, and they no longer meet the needs of the diverse communities they serve. For example, many parks are predominantly comprised of single-purpose sports fields that are rarely used. Can these public assets do more?

While the “Recreation” arm of the division remains robust, parks today extend far beyond leisure and sport; they are a form of critical urban infrastructure with overlapping benefits. Parks mitigate climate risks (heat, pollution, stormwater), support biodiversity, improve health (physical and mental), and boost economic vitality; yet they’re treated as expendable.

At the University of Toronto’s Centre for Landscape Research, initiatives such as Parks in Action and Quality in Canada’s Built Environment: Roadmaps to Equity, Social Value and Sustainability reimagine parks as essential to a resilient 21st-century city.

As the City searches for a new P&R Director, we have a chance for bold, systemic reform. Here are eight key actions Toronto could adopt:

1. Consider Parks as Urban Infrastructure

We don’t debate investment in roads or electricity grid upgrades, so why treat parks as secondary services? Parks should be integrated into the municipal spatial and physical planning structure. One meaningful change would be relocating P&R from “Community & Emergency Services” to “Development and Growth Services,” aligning parks with City Planning, Housing, and Development. This signals a paradigm shift towards parks as essential components of how the city is physically shaped. Other cities — from New York to Melbourne — already do this.

2. Create Nuanced Park Typologies

Toronto’s current park classification system allocates maintenance dollars primarily based on size, overlooking crucial factors like usage and location. According to the Auditor General report: “District Managers and Supervisors consider factors such as parks classification/size, location, and usage, in determining whether certain parks need a higher level of maintenance than set out in the service level standards” and there is a “a lack of consistency… resulting in discrepancies across Supervisors in terms of the span of their oversight.” This often means that high-use small downtown parks may receive less maintenance than larger, less-used suburban parks. There are also fewer Park Supervisors managing these busy parks. Toronto needs a classification system recognizing diverse park types—from ravine-edges such Riverdale Park East and West and Christie Pits to linear parks under hydro corridors. In denser areas, new categories like urban plazas or green squares for social gathering —“place” as they are called in Montreal—can clarify expectations of what is possible in small sites. Take the proposed “parks” at 464–470 Queen Street West or 229 Richmond Street West. These are small, dense spaces that cannot realistically meet community demands for playgrounds, splash pads, sports fields, and dog-off-leash areas. But by calling these sites an urban plaza from the onset, both public expectation — and design opportunities — shift.

3. Strengthen the Design–Maintenance Nexus

Toronto’s main challenge is park maintenance. Adopting a stewardship model for parks that would involve neighbours, volunteers, and local groups working alongside unionized city-crews fosters civic pride, safety, and shared responsibility. This is very much like the Toronto Nature Stewards who runs a stewardship program on public land in ravines and natural areas without direct City supervision,

Park design standards, such as installing toe-rail guards and wood and wire snow fencing around plantings, as is done in cities across the world, should be mandatory. Additionally, measures should be taken to prevent damage from maintenance trucks, snowplows, and dogs that can decimate plants (we really need better solutions for sharing park space with dogs). In high-use areas where grassy lawns consistently fail, resilient options like pollinator meadows or permeable paving should be considered.

4. Place-keeping Acknowledges the Land

Toronto parks sit on land with Indigenous, cultural, and ecological significance. Stewardship models informed by indigenous place-keeping should guide park management. This would see the protection of sacred grounds and ecological areas as interrelated. Guidelines would transform to further respect natural features, from biodiverse pollinator meadows to medicinal gardens and trees, as culturally meaningful. The Japanese honour their old trees, but Toronto’s risk-averse policies often lead to removing mature trees unnecessarily, not only on private land but also in parks; with proper care, many could be saved. Protecting trees, though expensive, provides immense benefits vital for a city fighting climate change.

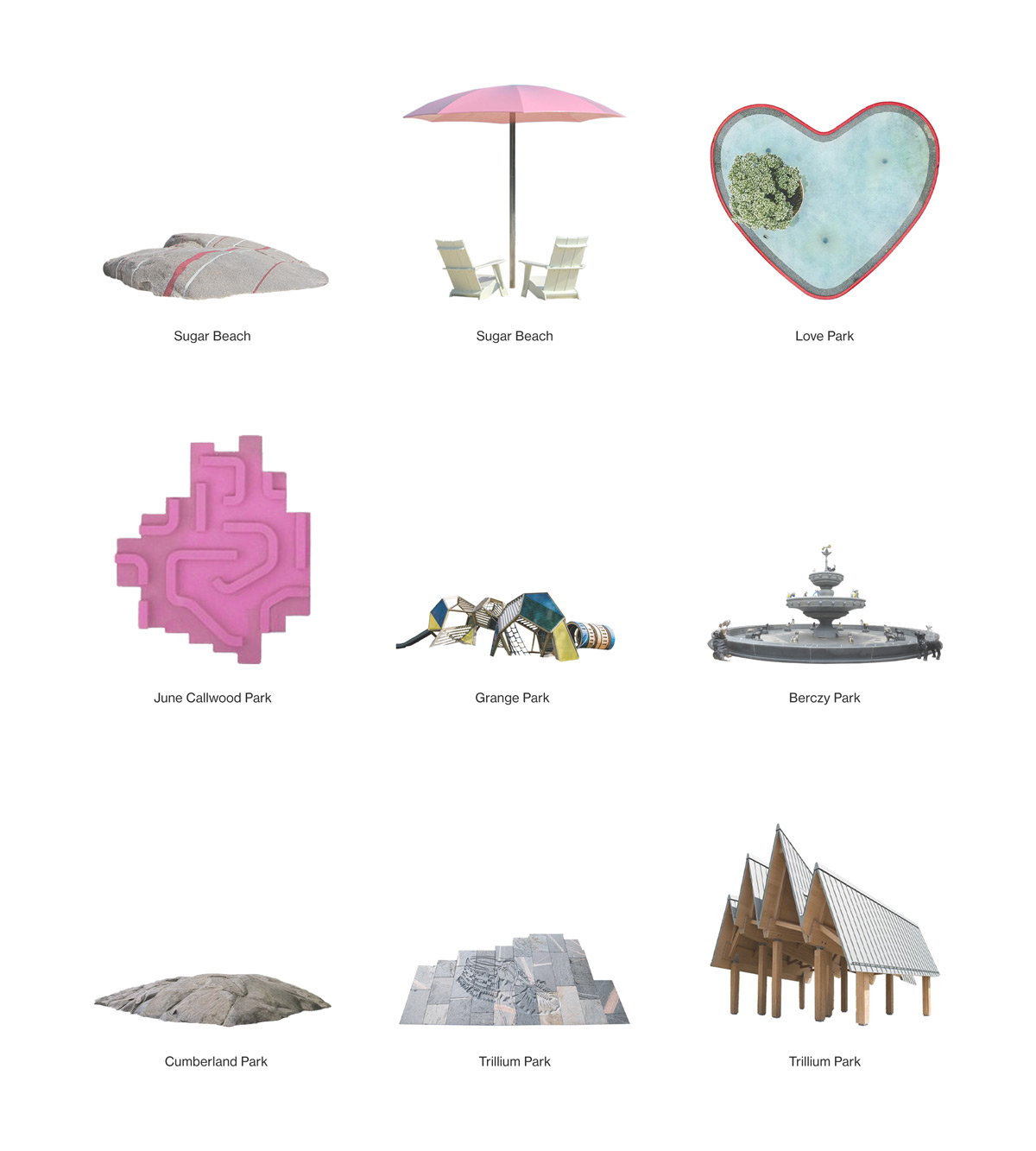

5. Parks Are Cultural Assets

Toronto boasts award-winning parks designed by internationally renowned landscape architects, such as Love Park, Sugar Beach, Berczy Park, Trillium Park, and the Village of Yorkville Park—spaces that deserve recognition as “flagship” parks and should be thought of as “habitable public art”. Yet these parks often suffer from careless interventions, such as the unsightly black and blue waste bins and improper maintenance of specialized elements. Montreal’s Bureau of Design provides a model for embedding design excellence standards city-wide, something Toronto should emulate, and echoes Councillor Matlow’s “Towards a Beautiful City” initiative.

6. Create a Vibrant Park Economy

While monetizing parks can be contentious, small-scale economic activity can enrich parks without compromising their public nature. Parks with concession or event income spend 23% less per acre on maintenance. Toronto should permit concessions like cafés, beer gardens, and kiosks featuring local vendors, food stands, and chair/umbrella rentals. Imagine hammocks and lemonade at Trinity Bellwoods in the summer, or hot chocolate at Grange Park in the winter. Parks around the world offer diverse retail options that activate parks year-round, providing residents with grassroots entrepreneurial spaces that can empower various population segments in the adjacent communities. The café by the Thorncliffe Park Women’s Committee totally transformed the once-neglected R.V. Burgess Park. The City should promote and encourage the use of its public lands to empower communities and build social capital.

7. Innovative Funding Sources

Bill 23, More Homes Built Faster Act, previously Section 42(3.3) of the Planning Act , requires all new development to contribute to the expansion and enhancement of the City’s parks and open space system. However, the distribution of the funds and where they are spent can be murky – often, they might not go directly to maintaining adjacent parks. Mayor Olivia Chow’s boost to the P&R budget is a good start, but tax dollars alone won’t ensure parks’ long-term health. New York’s Central Park Conservancy funds 75% of costs via private donations and endowments. Brooklyn Bridge Park sets a precedent for creative financing, such as smart covenants on adjacent real estate developments, directly spurred by the creation of the park.

Waterfront Toronto parks, such as Biidaasige Park and Corktown Common, are flood protection infrastructural park landscapes that enabled the construction of Ookwemin Minising and the West Don Lands, respectively. Their construction unlocked land values on public land using public funding that should be captured from developers. A covenant would ensure that a portion of the gains from the development is allocated to pay for the stewardship of these parks in perpetuity.

While Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS) have expanded the public realm, they often sacrifice accessibility and ecological considerations. We can do better — but only with political will for novel funding.

8. Trust the Experts

Community consultation is essential, but excessive consultation can stall projects. The Trinity Bellwoods path redesign exemplifies this issue—years of consultations have delayed necessary upgrades. Empowering landscape architects and park planners to lead technical decisions while remaining accountable to community goals ensures timely and high-quality outcomes. Design excellence requires feedback, expertise, leadership, and decisive action.

The Bottom Line

Toronto’s parks reflect our collective values and aspirations. Currently, they fall short—not due to lack of innovation, but insufficient coordination and vision. Reimagining our parks means fundamentally rethinking how we govern, fund, design, and maintain them. These proposals aren’t radical—they’re proven strategies from cities around the world. The only remaining question is: Will Toronto rise to the occasion?

Toronto park bins in beautiful places:

Fadi Masoud is Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture and Urbanism at the University of Toronto, and Director of the Centre for Landscape Research.

All images by Fadi Masoud unless otherwise indicated

3 comments

Planting trees are a good start. However, it takes decades for any trees to grow to maturity.

High Park was a sheep farm owned by John Howard. The sheep would eat the grass, no need for mechanical mowers, and also fertilized the grassland.

In 1873, the Howards deeded the property to the city for use as a “Public Park for the free use benefit and enjoyment of the citizens of the City of Toronto forever.” With the exception of Colborne Lodge and a small farming operation, this land was in a relatively natural state.

In 1876 the City acquired an additional 69 ha east of the estate. It was not until 1930 that the final 29 ha including Grenadier Pond (14 ha) was added, bringing the total size to 164 ha. However, 4.5 ha of marshland at the south end of Grenadier Pond was later given to Metro Transportation when the Queensway extension was built in the early 1950’s, leaving 159.5 ha in total.

The trees of HIgh Park are a result of over 150 years of growth.

There’s a certain amount of architectural snobbery at play here when a third of the article’s space is dedicated to “my god these bins sure are unsightly!” and not a single word is paid to any of the issues people actually care about like water fountains and parks not being maintained.

Interesting piece, lots to chew on. The section on the legislation should be corrected – Section 42 revenues are not for maintenance, it isn’t practical to suggest that development funds should support maintenance of nearby parks. Also, the current government radically reduced what parkland entitlements municipalities have through new development – amount of land or equivalent cash-in-lieu, eligible developments, quality of land, etc. Hope this helps the conversation!