We think of suburbs as places where the middle classes go to leave the city. But Richard Harris’s book Unplanned Suburbs: Toronto’s American Tragedy, 1900 to 1950 (1996) reveals that, for several decades around the beginning of the 20th century, Toronto actually frequently expanded through “shacktowns” on its edges. These shacktowns profoundly shaped how Toronto developed, and still have resonance today.

In these shantytowns, primarily blue-collar workers and their families bought small plots of completely unserviced land outside municipal boundaries for a cheap price, and built one- or two-room shacks on them as living quarters. While the plots were narrow, they were large enough to also support a garden with vegetables and perhaps and animal or two, which provided a valuable supplement. Over time, the owners would improve the lot, constructing a fully built small house. In essence, they were making buying a home affordable in part by substituting sweat equity for the labour cost of construction. While a few were in the skilled building trades, most figured it out as they went along, possibly with assistance from more experienced neighbours.

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, these unplanned, unserviced suburbs would eventually petition to be annexed to Toronto, so that they could get basic services – piped water and sewers, paved roads, fire protection. Much of Toronto’s east end, for example, as well as the Junction, were first developed and then annexed in this way. However, these areas were expensive to annex and service – the development pattern was scattered, so the density tended to be low, but the presence of existing buildings and roads made it awkward to add pipes. Facing mounting debts from these expenses, after 1912 the City of Toronto refused to accept any more annexation requests from the suburbs. (It is interesting to contrast this pattern with the resistance to amalgamation from both city and suburbs in 1997).

After that, these unplanned suburbs continued to evolve on their own. The most prominent was in the Township of York, north of St. Clair West, in and around Earlscourt (Earlscourt south was one of the last areas annexed, but Earlscourt North remained outside the city boundaries). These areas would be subdivided by a land company, but in contrast to later practice, the company would do nothing else, simply sell the land.

The economics of shacktowns

Shacktowns evolved because it was simply not economic for private developers (who were just starting to emerge) to build housing that workers could afford. Early small developers built houses for middle-class families who could afford to pay a price that covered the construction expense and a profit. Other middle class and wealthy families could hire architects and/or contractors to build their houses on the land they purchased. But (in an echo of today), it simply wasn’t economic to build houses that working-class people could afford and still make a profit.

The fact that the land outside the municipal boundary was completely unregulated was an important factor in its affordability. The City of Toronto had begun to institute basic building regulations. At first, these were to prevent fires, which in itself required more expensive building techniques. Later, public health reformers under the leadership of Medical Officer of Health Charles Hastings instituted basic hygiene regulations, including that every house should have a wash basin and a flush toilet. Flush toilets, Harris discovered, could account for up to 40% of the cost of a small house – making that housing even more unaffordable to blue-collar workers.

Another factor was transportation. Earlscourt was within (admittedly long) walking distance of the factories and other employment opportunities in the Junction, who had moved there because larger plots of land were available for horizontal assembly lines and stockyards. At the same time, due to Toronto’s private streetcar monopoly that lasted until 1921, there was no streetcar line that extended into this area – which meant the land was less attractive to professional builders and middle-class buyers, and therefore cheaper. But workers could still walk to the streetcar within Toronto’s boundaries if they worked more centrally.

This was also a period of very rapid population growth in a very young city, so there was little scope for “filtering” (where older buildings that were once expensive become more affordable over time). Lodging/boarding and shared houses were common, but not sufficient either. Harris calculates that the owner-built homes accounted for a third or more of new homes in the first decade of the 20th century.

The culture of shacktowns

Adding to the economics was a culture of individual home ownership that was particularly strong among the immigrants from the British Isles who made up the vast majority of the new population of Toronto in this period.

Harris shows that there was a general dislike among this demographic – both from middle class reformers and blue collar workers – for shared accommodations. The British Isles immigrants had left a world where owning property was out of reach in large part so they could find a place where they could have their own house and plot of land. This drive could put them into considerable danger. Having put all of their resources into a small plot of land and small building as early as they possibly could, they often over-extended themselves and had no cushion against misfortunes. When a recession struck in 1907 and many were out of work temporarily, many were in danger of starvation and freezing because they had no reserves with which to buy food or fuel, and they were not part of a municipality that could provide poor relief. They had to be rescued by charity. Harris notes that this culture of individual ownership was balanced by one of co-operative support, also imported from the British Isles, where neighbours helped each other with improving their properties and organizing services – all the more necessary given the complete lack of municipal services.

The result of this cultural desire for home ownership and the opportunities provided by shacktowns was that, by the 1920s, a remarkable proportion of Toronto’s population lived in owner-occupied private housing (rather than renting). That proportion reached a high of 60% in 1920, much higher than in any comparable North American city (next was Baltimore at 46%; Montreal was 16%), although it would subsequently drop for a period. It profoundly shaped the city into one dominated by individual, owner-occupied houses.

Such a drive was not universal. It was fascinating to learn that the largest non-British-Isles group in Toronto between 1900 and 1950 was Jewish people, largely from eastern Europe (about 7% of the population). They tended to stay central, because many worked in the garment trade. Since that business didn’t need horizontal assembly lines, it could operate in multi-storey buildings and, needing less land, could remain in central locations. At the same time, while many did purchase property (and some developed it), they appear to have put less value on property ownership (and more, for example, on education). When they achieved prosperity, many moved to Forest Hill – but a larger proportion than the British Isles population remained renters, which is why Forest Hill, despite its prosperity, had more apartment buildings than other similar middle-class and wealthy suburbs.

Private Zoning

One of the more remarkable insights of Unplanned Suburbs is the role of essentially private zoning, a role whose effects still resonate today. In this early period, the City of Toronto had instituted some very basic building regulations that had zoning effects, notably fire regulations that specified what parts of the city had to be built with more expensive fireproofing techniques such as using brick rather than wood.

One area that began what we would recognize as public zoning early was Forest Hill. Always aiming to be an exclusive, expensive enclave, it managed to carve itself out of York Township into a separate municipality at an early stage, and then promptly prohibited industrial uses within its boundaries, along with (less expensive) wood-frame houses. But in Toronto itself and some other suburbs, there was little of the area-specific zoning that we would recognize today until the middle of the century.

There was, however, private zoning. That is, the land development companies that bought up and subdivided land targeted specific areas to specific demographics. In areas targeted to a high end, such as Lawrence Park, lots were larger, but as well the subdividing companies established deed restrictions that specified how houses were to be built. An advertisement for lots in Cedar Vale specified that

“Each house or garage or coach-house must be of brick or stone, and must be built a certain distance from the street, must be detached, can be used for no business whatsoever excepting that of a dentist or medical practitioner. Buildings must be a definite distance from the next lot …” (p. 173).

We can recognize classic setback and use regulations that are now typical of municipal zoning, but at the time were being implemented by private companies. Areas aimed at the middle class, meanwhile, had smaller lots and fewer restrictions. Meanwhile, areas targeted at workers had small lots and no restrictions at all. Working class areas were, as noted above, often near the factories where the residents would work. While ads for wealthier areas emphasized their bucolic nature, Harris found a remarkable ad for lots aimed at workers where the lot is surrounded by smoke-belching – and wage-paying – factories (although in fact the area was quite bucolic too). In other words, often the initial zoning and economic nature of different neighbourhoods of Toronto was determined by private companies, and those characteristics can often still be seen today.

Another impact of these early developments that’s still visible is the difference between owner-built and developer-built streets. Harris contrasts streets where a developer built a series of houses and those where only the land was sold – which were often side by side – by the uniformity of both the style and the initial valuations of the one, versus the very random presentation and layouts, and valuations, of the owner-built streets, where owners could place their house wherever they liked on the lot. “At any moment the typical scene was anarchic,” he writes. “Given the way in which lots were purchased and homes were built, no two dwellings were alike. … Every house is unique in size, style, and setback” (p. 214). One realizes that in many case Toronto’s zoning regulations were imposed after the fact, following rather than leading development of a neighbourhood.

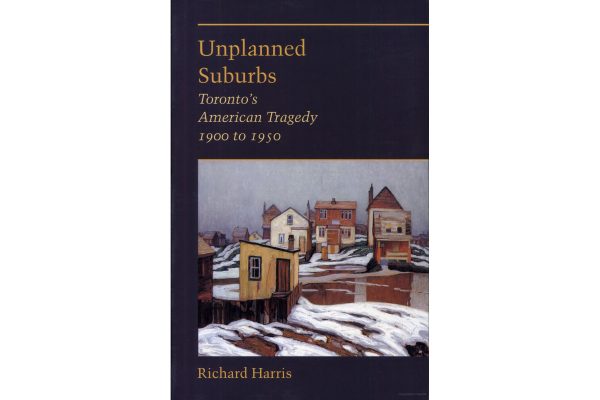

Before he helped form the Group of Seven, artist Lawren Harris painted several paintings capturing the eclectic, scattered nature of these shacktowns, including the one on the cover of the book (January Thaw, Edge of Town) and the rather more cheerful Spring in the Outskirts.

Decline and contemporary relevance

The shacktown phenomenon declined in the 1920s. Once services started to be implemented, the cost of those lots, both in terms of purchase and in terms of maintenance through taxes, went up. Water, sewers, and paved roads became expected, but paying for them meant increases in taxes. Once the TTC took over transit and expanded streetcar lines north into the suburbs, the value of the land also increased. Meanwhile, the existing owners had mostly built their shacks into full houses, which also raised their taxes. New development, meanwhile, was increasingly dominated by well-capitalized construction companies that didn’t just subdivide land but also built on it themselves.

When the Depression hit in the 1930s, quite a few of the working-class owners in former shacktowns, having lost their jobs, had to give up and move back to rental accommodation in the city – while their houses were sometimes purchased by middle-class families, perhaps themselves seeking less expensive accommodation in the suburbs.

Some of the workers who moved back into the city moved into houses that became split into lodgings or apartments – something that the larger houses in the city could manage, unlike the smaller houses in the former shacktowns. That process continued immediately after the Second World War, when the housing needs of returning veterans prompted another housing crisis. It’s interesting to see the origins here of the divided mansions that have been such a characteristic of Toronto’s older neighbourhoods (and are now sometimes being returned to single-family homes). That process was followed by a last burst of owner-building by veterans immediately after the war.

Equally interesting is the way that Toronto seems to have been in a housing crisis frequently in its history. As is the case now, it was not possible for private enterprise to build housing that could be afforded by working-class families. But of course we no longer have the option of shacktowns. For one thing, the city is too large – it’s no longer possible to have cheap land near multiple employment options. Equally importantly, we now have building and service regulations, for very good reasons, that make it impossible to build a wholly unserviced shack to live in on one’s suburban property. Harris points to the expansion of capitalist development as a factor in the end of shacktowns, making an interesting distinction between a decline in “building for use” (where an owner builds a house to live in on their own property, whether themselves or by hiring a builder) and an increasing dominance of “building for profit.” But equally important is the expectation that any new house should be solidly and safely built and be serviced with water, sewer, electricity, and so on.

One can point to encampments, of course, and Harris makes a distinction between those, similar to the ones today, that sprang up during the Depression in places like the Brickworks, and the shacktowns. In the shacktowns, there was clear ownership of the property by the residents (in fact often outright – they couldn’t get conventional loans) and both an ability and intention to settle and continue improving the residence. This clear title to property also distinguishes them from the shantytowns in many developing nation cities that otherwise resemble them. The shacktowns were always temporary, not in the sense that they could disappear, but rather in the sense that they would evolve into something more permanent.

Unplanned Suburbs is written in a straightforward and approachable style, and gives a fascinating insight into how Toronto developed, with a great deal of resonance for today (possibly even more so than when Harris was writing in the early 1990s). Toronto is again rapidly increasing in population and facing a constant crisis in affordable housing. The solutions today have to be different, but it’s always interesting to find historical resonances for our problems.