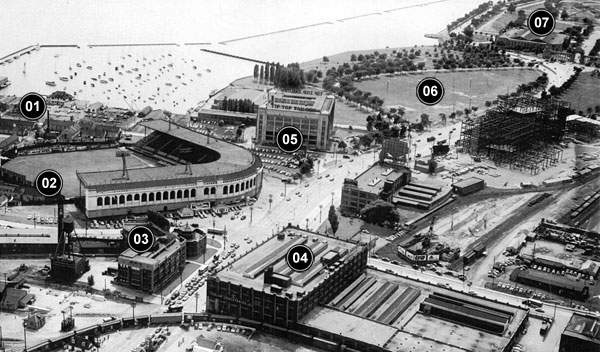

This is what the foot of Bathurst Street looked like in the 1950s. It was a brand new intersection back then; this land didn’t even exist until the 1920s, when the lake was filled in. The original shoreline was just to the right of this photo. That’s where Garrison Creek met the lake, and where John Graves Simcoe decided to build Fort York all the way back in 1793. The Fort, of course, is still there. But now they’ve snuck the Gardiner Expressway into the space between it and the right-hand edge of this photo. Today, part of that history is commemorated by a Douglas Coupland monument on the north-west corner of the intersection: in memory of the War of 1812, a Canadian tin solider stands victoriously over a toppled American one.

But not surprisingly, a lot of the neighbourhood’s most interesting history came soon after the new land was created. You can see a lot of it in this photo. So I thought I’d add a legend and give a brief virtual tour of the old hood. You can open a bigger version of the photo by clicking here.

We’re looking west. That’s Bathurst going from the bottom-right to the middle-left; Lake Shore Boulevard (which is also called Fleet Street for this stretch) is going from the top-right to the bottom-left.

01 Little Norway. At the beginning of the Second World War, Norway was officially neutral, but Hitler invaded and occupied the country anyway. The Norwegian King escaped to England and set up a government in exile, joining the war on the Allied side. What was left of the Royal Norwegian Air Force came to Toronto for training. They flew out of the Island Airport and had their camp just across the gap on the mainland — right at the foot of Bathurst. You can really only see the edge of Little Norway in this photo; most of it is off to the left. Today, that spot is home to Little Norway Park. You can still catch the ferry to the Island Airport in the very same place the Norwegians did back during the War.

02 Maple Leaf Stadium. One of Toronto’s most beautiful sports stadiums opened in 1926. It was home to the Maple Leafs, a minor league baseball team who played in Toronto right up until the 1960s. Some of the squads that called this stadium home were among the very best minor league teams in the history of the sport. Sparky Anderson — the legendary Hall of Fame manager of the Detroit Tigers and the Cincinnati Reds — played for one of them. In fact, this is where he got his start as a manger: the owner of the team thought Anderson would be better behind the scenes than he was at playing shortstop. The stadium was torn down after the team was sold and moved to Kentucky. Today there’s a gas station on that corner and a housing complex behind it. (You can see more old photos of the stadium here.)

03 The Crosse and Blackwell Building. This little Art Deco building is still there today. It was designed by the architects at Chapman & Oxley: the same firm responsible for the design of Maple Leaf Stadium as well as many of the other icons of Toronto’s lake shore: the Sunnyside Pavilion, the Palais Royale and the Princes’ Gates (number 7 in the photo above). The building was originally called the Crosse and Blackwell Building, because that was the name of the food company it was built for. Today, we just call it 545 Lake Shore Boulevard West. Rogers uses it as a home for some of their cable channels, like OLN and the Biography Channel.

04 The Loblaws Warehouse. Just a couple of years after Maple Leaf Stadium was built, Loblaws opened a new warehouse right across the street. You can see a freight train pulling up to it at the bottom of the photo, blocking traffic. The facility was on the cutting edge when it opened in the late 1920s — the “Google headquarters of its time,” as Heritage Toronto’s Gary Miedema told the National Post — with a bowling alley, billiards tables and a theatre all included to keep employees entertained. People were so fascinated by the building that tours were given to the public.

When Loblaws moved out in the 1970s, it donated the building to the Daily Bread Food Bank. And when the Daily Bread Food Bank moved out in the year 2000, Loblaws tried to demolish it. But the City stepped in and protected the site. Now it’s being redeveloped: the parts that aren’t protected are being gutted; there’s a plan to add condos towers, offices and a supermarket.

05 The Tip Top Tailors Building. Tip Top Tailors was founded by David Dunkelman, a Polish immigrant, in 1909. He started the company in a storefront on Yonge Street. But by the time the 1920s rolled around, he could afford to build these new headquarters down by the lake. The building is still there today — complete with the old iconic red neon sign — but now it’s the Tip Top Lofts.

06 Coronation Park. It was the 1930s before they decided what to do with this land. During the Great Depression, it was a construction site — in the fight against unemployment, the government hired people to build a seawall just offshore. They didn’t start work on the park until 1936, after the seawall was done. That’s when the old King George died. King Edward soon abdicated in the name of love, and the stuttering, new, Colin Firth-y King George took over. In honour of the crowning of the new king, a group of First World War veterans — awesomely calling themselves “The Men of Trees” and declaring that restoring green space was “the most constructive and peaceable enterprise in which nations could cooperate” — planted a big oak in the middle of the park. In honour of the military units who fought in Canada’s wars, they also planted 137 maple trees.

And they weren’t done there. In the years after that, even more trees were added — a series of paths curved through hundreds of them. In 1939, King George himself came to visit with his wife, the Queen Mum. They drove along what we still call Remembrance Drive, as veterans and schoolchildren planted trees for every single one of the public schools and high schools in the city. But over the following decades, much of that history was forgotten. Some of the trees died. Some of the plaques went missing. Most of the paths aren’t there anymore. In 2011, Councillor Paul Ainslie tried to have the park rejuvenated in time for this year’s 100th anniversary of the First World War (though the Internet doesn’t seem to have any recent news on that front). Now, Coronation Park is being mentioned by Adam Vaughan as a potential location for a national cricket stadium.

It’s also where The Grateful Dead played a free show in 1970. It was on the day of The Festival Express. Woodstock had convinced a lot of people that live music should be free. That day, there were violent clashes between hippies and cops outside Exhibition Stadium, where the concert was being held. As a way of keeping the violence to a minimum, The Dead and some other acts agreed to head over to the park after their official sets and play for the people who couldn’t — or wouldn’t — pay.

07 The Princes’ Gates. At the top of the photo, you can see the very eastern edge of the Exhibition Grounds — and the entrance at the Princes’ Gates. They, too, were built in the 1920s. The Princes were here to open it themselves: the future King Edward (who abdicated; older brother of the future King George) and their younger brother, who was also, confusingly, named George.

The Goddess of Winged Victory stands on top of the Gates, with a maple leaf in her hand and nine pillars beneath her representing the nine provinces in Confederation at the time. More recently, we’ve added a garden out front, with the official flowers of every Canadian province and territory.

A version of this post originally appeared on the The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog. Original photo via the Toronto Archives. A tip of the hat to Fort York and Garrison Common Maps for pinning down the date it was taken.