The City of Toronto Planning Department is proposing to introduce a new option for managing development, the Development Permit System (DPS), which could replace the current zoning system in some areas. I attended an information and consultation session about this proposal on the weekend, along with a room full of representatives of neighbourhood groups who were feeling a contradictory mix of anxiety and anticipation about the idea.

There’s no doubt that Toronto’s current planning and zoning system has problems. Residents don’t like it because it seems random and arbitrary, with outcomes bearing little relationship to the perceived rules. Developers don’t like it for similar reasons, as it embroils them in endless negotiation, especially the way that “section 37” money is extracted from them for what they perceive as reasonable updating of zoning. Planning staff don’t like it because it takes up so much of their time in negotiation, consultation and Ontario Municipal Board (OMB) hearings without any way of predicting results.

The Development Permit System, in theory, is a way to eliminate a lot of these problems and give everyone far more certainty and predictability in the development process. However, it also comes with costs.

It would not be applied city-wide, but rather to specific areas where locals (residents, landowners, councillors) want it and where it is appropriate for the local situation.

In its essence, the Development Permit system is a way to:

a) do a comprehensive re-zoning of an area, with full community and stakeholder input, to make it appropriate for the specific location, including its physical character and the density it could reasonably support.

b) ensure that new development can only be built if it strictly conforms to this new zoning.

Another way to think of it is in terms of “as-of-right” building. Currenly, any landowner can build a new building “as-of-right” according to existing zoning, without any complicated process. However, landowners have the right to apply for a re-zoning (and zoning in many growth areas of the city has not been updated), which leads to the endless and unpredictable development process we are familiar with. A DPS system would, in essence, a) update the as-of-right rules for an area, and b) make it only possible to build according to these updated as-of-right rules, but with a process that is quick and straightforward like “as-of-right”.

Under a Development Permit System, a series of stakeholder (community, councillor, landowners, etc) meetings would be held to develop a set of standards and criteria for building in a specific area. These can include maximum and minimum height, shadow impacts, process, materials — all kinds of things. Council would pass a bylaw implementing these standards. Once in place, any building proposed that fits these standards would be approved quickly by planning staff by being granted a development permit. Any building that did not fit these standards would be rejected by staff. Individual developments could no longer appeal to the OMB to get an exception from these standards.

I won’t go into more details of how it works — some information is available on the City of Toronto Planning Department website. Rather, I want to do a survey of some of the potential, and some of the issues, that this proposed system raises.

POTENTIAL

It’s entirely voluntary, and targeted

DPS would be just an option for communities. It would not be imposed on any community that didn’t want it — the community and local councillor would have to request the process in the first place, and the bylaw would have to be passed by council in order to have effect. Communities could take as much time as they need to get their standards right. Any community that was worried about the DPS could simply ignore it.

The boundaries of a particular bylaw for a particular area can be flexible, depending on what’s needed. Within a particular community, a development permit bylaw can be tailored for specific parts of the community, with different rules for different locations. In general, staff said they thought the system wouldn’t apply much to established residential neighbourhoods, but more to areas under intense development pressure. One place where a DPS might in fact be very useful is in employment areas — it could ensure such areas were only used for intended employment purposes.

The rules are followed

One of the things people hate the most about the current system is that is seems like there are no hard and fast rules, so no-one can predict what will happen. As a result, every development is a source of anxiety for everyone concerned. Under the new system, a community would know exactly what could be built, and so would a developer. It would save everyone a lot of uncertainty, stress and hassle.

In the view of staff, the current system a) promotes deviation from the rules, rather than following them, and b) is primarily reactionary. They see the DPS as a way of reversing both of those tendencies: promoting following of the rules, and being proactive.

Community benefit charges are predictable

The current “section 37” system is dreadful for everyone, essentially a form of institutionalized bribery that leaves everyone feeling dirty. Developers basically pay off the local community, through the councillor, in exchange for breaking the (often outdated) rules and adding more height. Developers cannot predict what they will have to pay, and the community cannot predict what they will get in exchange.

The DPS system would change that. There could be no breaking of the new height limits or other criteria. However, built into the bylaw could be a specific formula for community benefit payments when new height is added within the rules – e.g. if a new 10-storey building (in accordance with the bylaw) is replacing a 3-storey building, part of the process could be a per-storey payment to the community for each new storey, to help it absorb new residents. The community needs would be identified in the bylaw – e.g. restoring a dilapidated park in anticipation of new dog owners moving into the area. Everyone would know exactly what to expect.

The OMB can’t change the rules for individual projects

Once the bylaw has been passed, for individual projects a developer can only appeal to the OMB about staff interpretation of the rules (e.g. if the developer thinks the shadow impact is not as bad as staff believes). The OMB would have no power to change the rules, as it can with the current rezoning process by, for example, adding allowing greater height. If an OMB adjudicator did try to change the rules, it would be an error in law and could be appealed to a court, where it would be overturned.

The only way to change the rules is to amend the bylaw. Doing so would require community and stakeholder consultation, studies of the area (e.g. transportation) paid for by whoever wants to make the amendments, a report presenting the case why it should be amended, and then a full vote of council. It’s good that the bylaw can be amended — e.g. if an area received a new rapid transit line, it would be reasonable to increase density — but it’s not easy and it would require a well-founded case.

[Addendum: an article in Novae Res Urbis, July 18, 2014, which consulted planning lawyers, indicates that in fact site-specific applications are possible under the system. They take more work from the developer, who would have to go through the same process as required to amend the bylaw except the council vote, but they can be done, and so the OMB could overturn the rules for a particular site.]

Looks at the surrounding community, not just the property

Zoning applies just to a property itself. But a DPS could set “performance criteria” that judge the impact of a development on the community around it. So, for example, it could set not only a height limit, but also minimum sunlight requirements for neighbouring properties — if that criteria wasn’t met, the height might be restricted to below the set limit in a particular case.

Conditions can be applied

Staff could apply conditions to a permit, such as protecting valuable trees, or easements for public access, or replacing rental units.

However, these conditions could be appealed to the OMB.

It could speed up mid-rise development

In a recent article, Robert Freedman writes about the challenges of encouraging mid-rise developments along the “Avenues” in Toronto. A DPS would address some of the challenges he describes — it would enable developers to get much faster approvals for smaller projects; it would give them, staff and locals much more confidence about exactly what can be built; and it would ensure that the City’s mid-rise building standards, whose careful logic Freedman explains, would indeed be standards that ensure vibrant streets, rather than “a starting point for bargaining and negotiations.”

A DPS also has the potential to reduce speculation on potential development lands, which are sometimes priced according the potential of a big rezoning rather than to their existing zoning. Once land buyers know exactly what can be put on a piece of land, it could reduce speculation and create more realistic land prices, making mid-rise development more affordable.

At the meeting, one resident suggested that a template DPS could be created to help people understand what is involved (and speed the process of creating them). The City’s Mid-Rise Standards are in fact a pretty useful starting point for a Development Permit bylaw on an “Avenue” area.

It’s not a new system

The Development Permit System is already being used in BC, Alberta, Manitoba and Nova Scotia. It’s been generally successful in these provinces. The Ontario version has some adaptations to work with our unusual OMB situation, but the basic principles are similar.

ISSUES

There are a lot of issues with the DPS system, too, though there are ways they could be addressed.

The initial bylaw can still be appealed to the OMB

After council passes the bylaw, there will be 20 days to appeal it. Landowners and developers could appeal to the OMB, and at that stage the OMB could change the rules that were agreed to, for example giving a particular owner additional density. This change would be locked into the bylaw — it could only be removed by rescinding the bylaw or going through a long amendment process. (Note: communities would also have the ability to make “third-party appeals” at this stage).

One can imagine, for example, that if one landowner managed to get a certain height under the old system, and the bylaw sought to avoid a repeat by setting lower limits, the OMB might decide adjacent landowners could get the same height. On the other hand, without a DPS ther’s a good chance the same decision would have been made, or possibly even more height allowed.

Communities can’t appeal a specific permit

If City staff decide a proposal fits the local bylaw, there is no ability for the community to appeal that decision (“third-party appeal”). Also, there is no requirement for community notification of a building permit request. The idea is that the process matches the current “as-of-right” system, where a builder can just build something without telling anyone other than city staff, as long as the proposal is within the current zoning.

However, under a DPS, if a developer feels staff have misinterpreted the development permit bylaw, they do have the right to appeal the interpretation to the OMB. Essentially, that means that there is no built-in community scrutiny of staff decisions, but there is built-in developer scrutiny.

CORRA (Confederation of Resident and Ratepayer Associations) has expressed a lot of concern about this issue, e.g. what happens if staff allow excessive building based on a flawed shadow study? The community would have no opportunity to make their argument before it was approved. On the other hand, the scope for error remains limited to the details — the overall size and nature of a development could not vary much. As well, there’s a question of how effective third-party community interventions at the OMB are under the current system.

One partial solution to this gap in the DPS is that a bylaw could specify community notification and a community meeting ahead of a permit being issued, if a development was above a certain size. That way the community could have some input into the staff decision. A further possibility is to require a design review panel for larger developments, to ensure they are of high architectural quality.

As well, the DPS would allow council to delegate decisions about permits to citizen committees — so, for example, staff decisions (or, just decisions on large projects) could be reviewed by such a citizen’s committee. It’s no panacea but it could be another way to ensure community input.

It’s still a weakness, but several residents’ associations representatives at the meeting described it as a tradeoff that was worth it in exchange for the system’s predictability.

Focus on planning staff

The DPS puts a lot of power into the hands of planning staff. They no longer have to answer to the community, councillor or, for the most part, to the developer once the bylaw is in place.

The City’s planning staff are of high quality, but they are currently overworked. There is definitely more vulnerability to staff mistakes with the new sytem. Solutions could include hiring more planning staff, and instituting a robust internal review process. Public consultations could also help avoid mistakes, but would of course take more staff time.

Over time, if the parts of the City that are busiest in terms of development came under a DPS, a lot of staff time could be freed up by reducing the amount of OMB hearings, negotiations and consultations that are required. But a big investment in time is required at the front end to consult with stakeholders and establish the bylaw in the first place.

Another problem is that the bylaw requires a permit to be issued or refused within 45 days or the developer can appeal to the OMB. Staff at the consultation said meeting this time limit was essentially impossible for staff, but argued that they would still come to a decision faster than an OMB hearing could be scheduled, so it wouldn’t be worth it to appeal.

Can communities really agree?

An assumption in the DPS is that communities could agree on detailed standards for their area that include increased density in certain areas. It is definitely not the point to lock the current outdated zoning into place. However, one can imagine that’s exactly what many residents would like to do. It would be bad for the city as a whole if the DPS was used to freeze existing densities into place, because the City’s official plan counts on increased densities in growth areas of the City to absorb new populations, support increased investment in transit and other infrastructure, and make the city more sustainable.

It’s not entirely clear how these kinds of conflicting visions could be resolved, but the threat of appeal of a new bylaw by landowners after council passes it might help ensure that appropriate density is allowed for in the first place. Also, a DPS bylaw is not allowed to conflict with the Official Plan, so it could not freeze growth where the Official Plan encourages it.

The process also puts a lot of up-front demands on a community — they have to go to a lot of meetings, learn a lot about the possibilities, and commit to locking in the new rules up front. On the other hand, the process will be free and easy to access, and communities will not need to hire experts, which they currently do if they go to the OMB.

It seems likely to me that the first DPS areas will be places that are already under severe development pressure, where the community will be willing to accept increased density in exchange for certainty about what they will get; or perhaps places that have seen one outsized development and would be willing to agree to smaller increases in exchange for avoiding a repeat.

Lack of flexibility

While certainty is a huge advantage for the DPS, it also means that the system lacks flexibility. There is not even a possibility of appealing to the Committee of Adjustment for minor adjustments (a process that has its own issues of unpredictability).

One way to allow flexibility is for the bylaws to not go into too much detail about how exactly buildings can be built (shape, materials, etc). However, from what I’ve heard of the system in other provinces, micro-managing new building can be a temptation for those setting the rules.

There is also the possibility of incorporating exemptions into a DPS bylaw, but that would normally be for minor things. The ability to impose conditions also provides some potential for flexibility (e.g. creating new public access through a building), reducing the need to micro-manage the bylaw up front.

Another possibility is for an area bylaw to allow height/density trading within the area. A landowner who is only interested in renovating their existing building could sell some of their allowed height to a neighbour who wants to build taller. This could help provide some variety to a streetscape and allow more varied light onto the street. (One could also allow a landowner to shift height around within their own parcel). Such a system probably wouldn’t work where there are large residential areas (since some residents could end up getting less sunlight than others), but might work in more broken-up areas in the centre of the city; brownfields and employment lands with a lot of empty space; and also for areas with some heritage buildings (where owners of heritage buildings could get money for preservation, and ensure its permanence, by selling density or height rights to owners of non-heritage lots).

Only a few DPS bylaws would be passed a year

It was a measure of the weird mix of excitement and anxiety in the consultation that the room was simultaneously anxious about having a new system imposed on them, and frustrated that staff said only about 2-4 Development Permit bylaws would be issued a year (staff estimate the process of establishing a DPS area might take a year). Staff might provide criteria for choosing which areas to look at first, but it would be up to councillors and city council to put areas forward and decide who goes first.

It will be many years before even half the city would be covered by a DPS. In the meantime, the rest of the city would still be governed by our existing, frustrating planning system.

So a DPS is just one part of the solution. The City would also need to take steps to improve the planning process in parts of the city that stayed with the zoning process. One way to do so would be to establish secondary plans for a larger number of areas. In some cases, Heritage Conservation Districts might be an appropriate solution. City Planning would need to make sure other areas aren’t neglected as the DPS system is implemented in a few places.

Concluding thoughts

At its core, the DPS frontloads the role of the OMB, developers, politicians and community in the land use process into the initial bylaw development. Once a bylaw has been passed, it removes some of their power over individual cases and and gives it to staff . It’s not ideal, but one can argue it might be better for staff to have a final decision than the OMB. There are ways to incorporate some community input, and community appeals to the OMB were always a high, expensive and uncertain hurdle in any case.

I’ve seen some considerable fear and agitation about the Development Permit System. While it has drawbacks and flaws, I don’t think it deserves any kind of extreme reaction. Our planning process is really messed up, and it’s very good that the City is looking for alternatives that can make it better. It’s crucial to keep in mind that the DPS won’t be imposed on any area — only communities and councillors who actually want it will get it.

At the consultation, staff said they figured either no-one would want to convert to a DPS, or they would be overwhelmed with requests — they weren’t sure which way it would go. It will be interesting to see how it plays out.

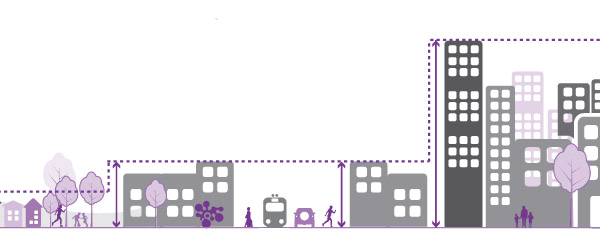

Graphic from the City of Toronto

10 comments

Very helpful – and the balance is very much appreciated.

A few interesting comments I’ve received on social media:

– MPP Rosario Marchese is concerned that the restriction on OMB action in a permit appeal is not as clear-cut as staff suggest: “If OMB ruling cites law, but then “interprets” it by ignoring it, very difficult to prove error in law”

– Jessica Wilson of CORRA notes that planners aren’t consistent on what kind of area they think a DPS would apply to. Thinking about it further, my feeling is that it’s unlikely after all to be applied where major developments – tall towers – are going in, because they’re just too big to be something that pops up suddenly with little process or discussion. DPS might apply better to, for example, places where mid-rise development is happening or expected to happen. But there’s no way to really predict.

– Wilson also notes that in DPS pilot areas, there were in fact developer appeals to the OMB right after the 45 day limit, and “somewhere it was observed that a “minor industry” quickly grew up around challenging whether applied criteria or imposed conditions were compatible with the OP or whatever.”

This was a fascinating read on an issue I do not know enough about. Clearly Toronto needs to reform its planning system to better meet the redevelopment challenges it has; this seems like a good alternative. Though as you point out it might take years to roll out the time and cost saving once the first few critical regions have bylaws could be dramatic.

Part of me worries that there’s nothing to stop the most well-organized, vocal members of some neighbourhoods from seizing control of the DPS process and using it to freeze densities and forms at their current level (even more so than they already are.) New as-of-right zoning does nothing if you don’t end up getting the ‘right’ to build anything except what’s already there. Anybody assuming that a DPS process (initiated by ‘neighbourhoods’) will result in broader permissions, is, I think, taking a long shot.

I live in Scarborough, and even though there’s a couple of giant slab towers just down the street, any *new* housing that’s not a detached bungalow brings out an angry segment of the neighbours who are seemingly allergic to all change. And just by invoking ‘neighbourhood character’ and the status quo, new buildings above the existing zoning can be easily vetoed. Only the developers with patience and money can usually overcome these hurdles. (Hey, anybody ever wondered what happened to all those small homebuilding companies we used to have?)

But why should the neighbours have this power, anyway? Now, things like shadowing and traffic and noise pollution are understandable grievances if they seriously, directly impact one’s enjoyment of one’s own home. But otherwise, why should people be prevented from building housing and workplaces for as many people as they want, on land that they own? What if the neighbours don’t like the colour I paint my garage door – or maybe they think I should have a paved yard instead of shrubs. Should there be meetings where the loudest complainers get to make rules on what my house must look like – because, after all, it’s “their neighbourhood”? Where’s the clear distinction between these “little things” of appearance and the “big things” of size and height and use?

This DPS is described as “voluntary” – not imposed on any ‘community’ that doesn’t want it. But who defines that? I love growth, and mixed uses, and density – so any DPS that makes a permanent, appeal-proof limit on those things is an ‘imposition’ on me. ‘Community’ is a word that carries a lot of, frankly, unfounded assumptions. It seems usually to mean “those residents who show up to consultations and convince ‘expert’ staff that their preferences be made mandatory.” What about the people who don’t live there yet, but would like to? Or the people who live there, but cannot stay unless change happens? Or who can’t show up? Or whose preferences are not reflected by a self-identified ‘community majority’? What, in other terms, is so elite and wise about the denizens of the status quo?

Dylan is right – the planning system in Toronto, as in many cities, is very broken. But I am skeptical that the DPS is any kind of solution.

While I share the concern that Benjamin has, overall DPS feels like a big step to the right direction. In principle it is a much better process that the one we have today. It should be possible to avoid the scenario that Benjamin describes if the long term growth plan is used to guide the process of establishing the DPS zones.

Benjamin, you have a point with groups saying “don’t do anything anywhere”.

But the flip side is that developers buy a property with a bungalow on it, sever it, build two narrow tall houses, and sell at a profit. This is not as clear cut a case as my allowed to do what I want to my house, since the developer is in and out.

I live in Long Branch, and this is happening on every street. Some of the new houses fit reasonably into the character of the neighbourhood, or at least to my aesthetic tastes. The generic stone-faced mansions that look like they should be in Brampton, but have been photoshopped to be half as wide to fit on the narrow lot, those I have problems with.

I actually renovated my house and had to go to the Committe of Adjustments, since my lot was only 25′ wide originally with a detached cottage squeezed up against one property line. But I didn’t replace it with a generic stone veneered house, I managed to keep the front half, with an addition on the back.

Well, developers do develop, and sometimes they make pretty obnoxious buildings. I live in a neighbourhood with mostly 1950s and 60s bungalows, plus a few tower blocks of similar vintage. A few of the bungalows have been torn down in recent years, and the replacements have been of the boxy faux-stucco and granite-veneer variety. I really dislike how they look. But I disagree that they should be restricted by reason of “neighbourhood character”. I think we would see much better redevelopment if the rules were, in fact, looser – so that landowners didn’t have to maximize their investment in land by kicking up big pompous stucco boxes, but could do something like three-storey townhomes, or a small apartment block on a few lots assembled together. There are a few of these in my neighbourhood as well (built on old industrial/commercial lots) and they’re quite nice. If developers could build something besides single family homes, I suspect they would (as they do downtown.)

I object to most of the planning system in Toronto because, outside of a few areas, it seems to have halted the ‘succession’ process, whereby low-density buildings are gradually replaced with higher-density ones. One result of this is that the GTA sprawls out indefinitely. Another is that housing prices keep rising as the limited supply of houses close-in to the city become ever more expensive. I think Torontonians are not exposed to this process much because most of the city is ‘first-layer’ development – that is, it was farmland or forest before. But a city can’t freeze itself in time and decide that the ‘character’ of existing neighbourhoods needs to be permanently maintained. This is especially true with regards to mixed uses – my neighbourhood has one coffee shop, one grocery store, one pizza place, etc. Alternatives are a half-hour walk away (and I cannot drive.) The neighbourhood could support more commerce, but there’s nowhere zoned for it. Even as the population of the region grows by 100k a year, my neighbourhood is losing population, because elderly people are living alone in bungalows, because it’s not legal to run a sublet here. But if you try to change this, and it’s all ‘neighbourhood character must be preserved’.

Yu: I understand that the DPS process might, *in principle*, not result in less housing growth. But it seems to me just as vulnerable to political capture and anti-growth factions as the current system, especially in the most expensive neighbourhoods. Does anyone seriously believe that a Rosedale DPS or a Lawrence Park DPS will include lots of as-of-right development areas, even though they’re adjacent to subway stations? I suspect that these neighbourhoods will use the DPS process to decide that no, actually, they’re perfect the way they are, and that all growth and demand can go somewhere else, preferably in Peel Region or Leslieville or something. It could be like the Beaches, where even a mid-rise condo is treated like the Coming of the End Times, regardless of ‘growth plans’. And then, after bylaw passage, there really will be no appealing to the OMB because of Places to Grow or adjacent owners. It’ll be stuck, indefinitely.

Ed: I sympathize with the trial of dealing with the C. of A. It’s a bureaucratic vacuum from which many honest proposals never emerge. But I submit that the right to put an addition on your home is, ultimately, indistinguishable from a right to build a stupid grey Mississauga Mansionette. The aesthetic objections you raise could be raised against almost any change – or even just a perceived “lack of maintenance”. Suggestions that these problems of taste be resolved by neighbourhood consultation run into the same old problem: just because some people get together and vote on it, doesn’t mean they get to do what they like with my stuff. Lots of folks like a paved front yard – I think it looks like crap, and I’ve busted one up at a house I lived in. But if all the neighbours got together, and decided that I shouldn’t be allowed to put flowers in where concrete had been – should they be able to stop me? I don’t think so.

I just got directed to this site; I hope people are still reading it.

The Development Permit System is an interesting idea, and Lord know the system we have now in Toronto stinks.

Perhaps we should be asking questions from a different point of view. For instance – what benefit is it to the inhabitants of a neighbourhood to see a developer move in with a big new project (and I use that term deliberately – they all look big to someone used to living with a two-storey house next door)? They get the following – old friends and neighbours move away; messy, noisy demolition; lots of established trees and greenery destroyed; months, years even, of the noise and disruption of the building process; the streets and traffic disrupted; the local landscape is now changed and usually not for the better – parts of the sky blotted out, big shadows cast where once there was sunshine; then a whole lot of strangers move in with all their business and cars and the traffic is much worse and there will be local lineups, and…. So tell me again why anyone living in an established neighbourhood should welcome development. In fact, I suspect no one does except the developer-predators who live by spoiling the neighbourhoods of others, and the politicians whose egos or fund chests are dependent on this process.

Now, I am exaggerating, of course – I like development as much as anyone when it is away from me – but only to a point, because the development process does very little to benefit the locals, except perhaps by raising the prices of their houses so they can move away to somewhere unfamiliar, and then get pushed on again just as they have got used to their new homes.

Perhaps an answer lies in compensation. The developer benefits greatly by buying property valued with a low density and gets to sell denser, high-valued property. It seems only fair that those close-by that he has annoyed and inconvenienced and subjected to a lower quality of life should get some compensatory benefit, in accordance with how close they are to the disturbance.

The impact without compensation is exactly why people living in a neighbourhood have every incentive to try to prevent development – or at least, why there’s so few local defenders for most new development, since almost by definition, the people who will benefit from it (the new residents or workers in the new building) aren’t there yet.

Tedsy,

What you’re describing is (maybe) a thing that’s been talked about by some people as ‘tradeable rights’. Here’s one way it could work: existing zoning is turned into ‘rights’ – everybody gets to build up as high or as big as current zoning says they can; since they bought with this in mind, this is relatively fair. Then, individual property owners are allowed to ‘trade’ with each other for impacts that new development will cause – noise, air pollution, shadowing, road traffic, loss of street parking – effects that cross over property lines, essentially. So, if you want to build a very tall building, you would have to buy ‘shadow rights’ from the neighbours; if you wanted to open a late-night bar, you would have to buy ‘noise rights’ (or maybe just more soundproofing.)

The benefit to a system like this is that it changes the choices. Under current zoning, neighbours don’t lose out on money because they prevented development – they would get nothing either way, or would get some minor “Section 37” benefits which are supposed only to go to neighbourhood amenities. With ‘tradeable rights’ everybody gets to keep what they have, but can weigh whether it’s worth it to them to miss out on compensation money they might get. And if you turn down development in your area, that money will go to someone else more willing. And of course, it’s less corruptible by political considerations, and is tied directly to the impacts that development imposes.

I think a model like this would do a few things:

1. More growth in richer neighbourhoods. Lots of people (with lots of money) want to live in Moore Park or the Kingsway, but the city’s plan currently identifies these areas as “stable”, so the incumbent homeowners keep the supply of housing fixed, and excess wealthier buyers go to affordable areas and bid up prices. More growth in wealthy areas should help avoid affordable neighbourhoods becoming suddenly expensive.

2. Continue to keep very loud, very dirty uses separated from neighbours who don’t want it nearby – since it would be prohibitively expensive to compensate everybody.

3. Making development in low-rise neighbourhoods a gradual, low-height process. If you drop a 30 storey tower in a rowhome neighbourhood, you’ll have a lot of folks to compensate. But a 4 storey six-plex would probably only have to pay the immediate neighbours.

4. Give builders more choice, and help small builders compete. When, as now, only a few locations in the city are available for any development *at all*, of course the developers go for the absolute max height, and the biggest developers win the bids. (It’s like people desperately rushing for the last open seat in a game of musical chairs.) However, if the whole city is open to development on traded rights, it’s more possible to do small, context-sensitive developments.

5. Letting people build and do things on their property (build a shed, run a small business in their garage, etc.) without jumping through bureaucratic hoops – as long as the impacts on the neighbours are negligible.

The big question for this system, of course, is what impacts count for compensation purposes, and which don’t. (Like ‘neighbourhood character’? What is that, exactly? I’ve never seen a good definition.)

It recently become apparent that the main advantage claimed for the DPS isn’t actually the case.

Chief Planner Keesmaat (who unlike all previous Chief Planners, was not a City Planner prior to being hired into this important position, but who was rather hired from private practice—google ‘Who hired Jennifer Keesmaat’ ) has repeatedly claimed that, unlike existing area-based tools also capable of incorporating a community “vision”, developers cannot apply to amend an adopted DPS by-law on a site-specific basis. So, for example, Keesmaat said on the Feb 25 TVO Agenda, at 28:40, “You can’t appeal just one site. You can only appeal the whole thing”. This inability to appeal on a site-specific basis has been pitched as the “magic bullet” that is supposed to prevent developers coming in and subverting whatever area-based plan you’ve got in place.

But it turns out to be false that applicants can’t appeal a DPS by-law on a site-specific basis. The Ontario Regulation 608/06 does not prevent this—as Lake-of-Bays Planner Stefan Szczerbak noted, they get site-specific amendments for their DPS by-law all the time. Joseph D’Abramo confirmed that the restriction is supposed to be part of the Toronto draft Official Plan Policies for Implementing a DPS in Toronto… but it turns out that these don’t forbid site-specific amendments, either—they just make it a bit harder for developers to do this. They have to do things like have an “area-based planning rationale’ (that’ll take them a lunch hour) and a “strategy for consultation’ (which is already required for any site-specific amendment of an area-based policy) and a couple of other hoops which developers will find it trivially easy to jump through.

Moreover, top planning lawyer Dennis Wood of Wood Bull confirms that the Planning Act does not allow any restrictions of amendments… so even supposing the Toronto version of the DPS did impose real restrictions—which is doesn’t, really—they would be challenged in court as overly onerous and ultimately illegal by lights of the Planning Act.

Meanwhile, the DPS is clearly deeply risky and problematic from the point of the view of the community (as opposed to developers, who may well embrace the fact that permit decisions will be accomplished in 45 days, rather than 180 days as is presently allowed, and that no public consultation is required, and that no 3rd party appeals by the community or others are allowed on permit decisions). For example, there is no guarantee that the community “vision” will be ratified by Planning in the proposed DPS by-law, and moreover, whatever by-law Planning puts forth can be changed by the OMB upon developer appeal.

And the day that the OMB decides—say, to allow 30 rather than 20 storeys—the existing zoning for the entire area is repealed, and all future applications for up to 30 storeys will be as-of-right, with no public consultation required, and no possibility for 3rd party appeal.

The Official Plan Policies for Implementing a DPS in Toronto are coming to Council on July 9. Google ‘CORRA The DPS from the community perspective’ to get the most recent scoop, building on Dylan Reid’s excellent article… get informed and WRITE YOUR COUNCILLOR.