It has been nearly 200 years since the intersection of Queen & Spadina was born. When the two roads first met, Toronto still wasn’t even a city yet: it was the town of York, home to less than two thousand people. Queen Street had been one of the very first roads the British built when they got here, part of the original plans for Toronto all the way back in 1793. They called it Lot Street back then, the northern edge of the first few blocks built in the new town (right around the St. Lawrence Market). A few decades later, it was renamed in honour of Queen Victoria.

By then, Spadina had also been built. It was laid out as a wide avenue by William Warren Baldwin, a doctor and lawyer who also designed Osgoode Hall and would play a leading role in the political struggle for Canadian democracy. He had just built a brand new house on his sprawling country estate; it stood on the hill above Davenport: the original Spadina House. Baldwin had the grand avenue carved out of the forest south of his home in order to get a better view of the lake. The estate, the house and the new road would all be given the same name: Spadina. It’s an Anglicized version of an Ojibwe word: “Ishpadinaa” (“a place on a hill”).

So it was when Baldwin built his avenue in the 1820s that the intersection of Queen & Spadina was first created.

Back in those early days, the intersection was way off on the outskirts of town, just outside the official border of the tiny new Upper Canadian capital. But it didn’t stay that way for long. Toronto grew quickly over the course of the 1800s. By the time the early 1900s rolled around, Queen & Spadina was at the heart of a bustling metropolis.

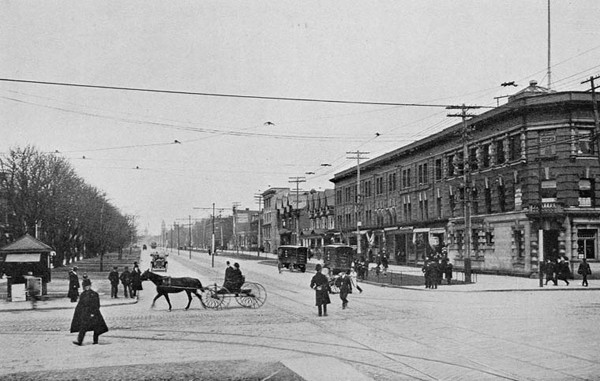

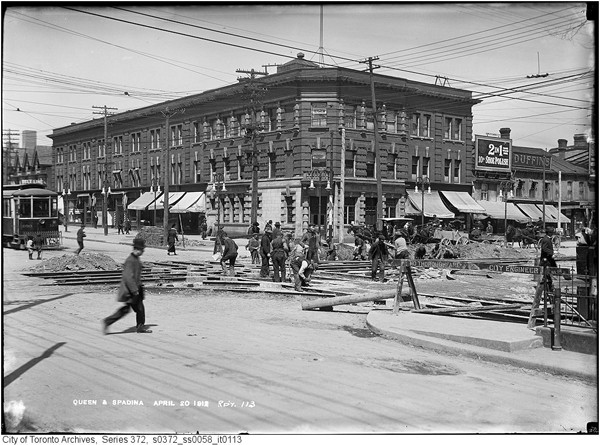

By then, some landmarks that are familiar to us today were already there. The Bank of Hamilton opened on the north-east corner in 1902. It’s been there ever since; it’s home to a CIBC branch now. You can see it in the photo above (from 1908 or ’09) and in this photo from 1912:

You can also see it in this photo from a night in the early 1920s. The new streetlamps had just been installed about ten years earlier — at the same period when power lines from Niagara were bringing public-owned electricity to Toronto for the very first time:

And the Bank of Hamilton isn’t the only building to have survived the last hundred years. The building on the south-east corner — today it’s a Hero Burger — was already there a century ago. It’s been there since the 1880s, originally a dry goods store designed by the architectural firm of Langley & Burke. (They’re the same fellows behind the Bloor Street Viaduct, the Necropolis Chapel, and churches and cathedrals like Metropolitan United, Trinity St. Paul’s, and the spires of St. James and St. Michael’s.) It’s been there so long, in fact, that the column in front of the door to the building has been worn away by the countless hands that have touched it over the last hundred and thirty years. Right now, it’s protected by plywood and propped up until it can be restored.

You can see the building, with its iconic turret, in this photo from 1910, which was taken looking east down Queen Street toward the intersection:

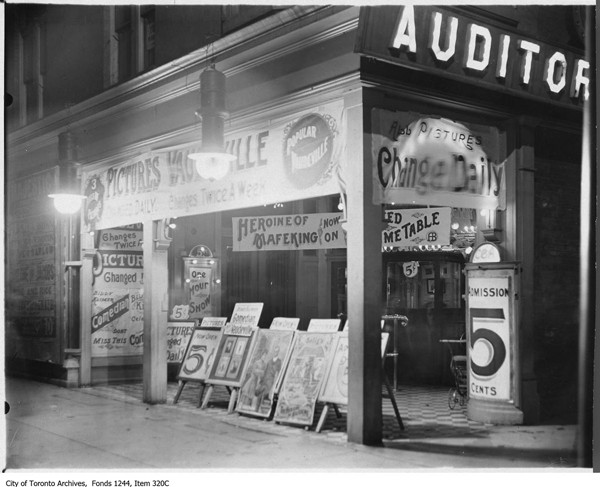

But of course not every building overlooking Queen & Spadina in the early 1900s has survived the last century. The building that stood on the north-west corner back then is gone today. The spot is now home to McDonald’s. But back in the early days of film, it was a movie theatre that stood on that same corner.

The Mary Pickford Auditorium was named after Toronto’s first big movie star. She had been born on University Avenue (where Sick Kids is now) back in the late 1800s and launched her acting career as a young girl on the stages of the theatres of King Street. Before long, she’d moved to the United States, where she quickly became one of the very first superstars of the silver screen. At the time the Mary Pickford Auditorium was charging people a nickel to watch movies at Queen & Spadina, Mary Pickford was one of the most famous people in the entire world.

You can see both the Mary Pickford Auditoirm (on the left) and the Bank of Hamilton (on the right) in this photo from 1910. It also gives you a good view of just how wide the sidewalk used to be on that north-west corner outside the theatre:

The pole in the middle of the photo seems to be a streetcar stop — right on the very same corner where we still catch the Queen streetcar today. They were rumbling through the intersection back then just like they do in the 21st century.

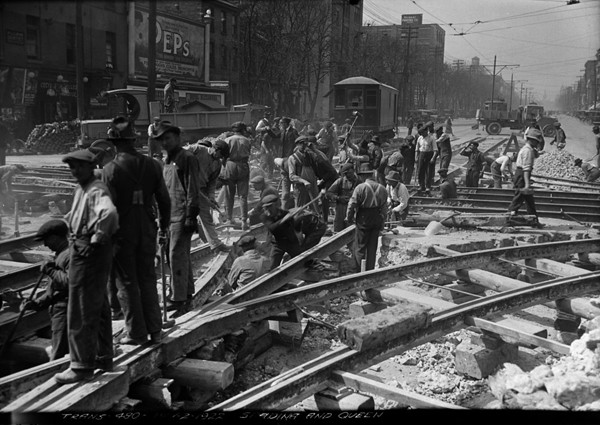

Here you can see some streetcar track work being done in the spring of 1912 — much like the track replacement that shut down the intersection for two weeks a hundred years later, during the summer of 2012:

And here again in 1922:

And here is the Queen streetcar itself, picking up passengers at Queen & Spadina during the First World War. We’re looking at the south-east corner of the intersection — that’s the Hero Burger building behind them:

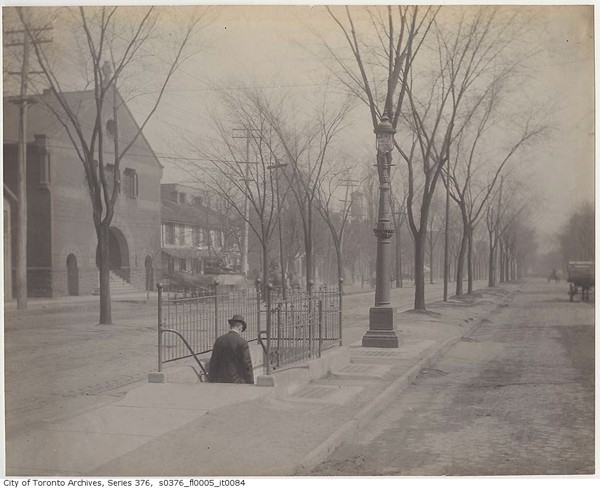

But one of the most interesting features of Queen & Spadina had nothing to do with buildings or transit. It was in the middle of the intersection, buried beneath the ground: a public washroom. You got to it by descending a subway-style staircase in an island in the middle of Spadina, just a bit south of the intersection. It’s at about the same spot where you get off the southbound Spadina streetcar today. Here’s someone heading down to relieve himself during the 1890s:

You can also see the entrance to the washroom in this photo, looking south from the intersection in the winter of 1914:

And in this one, we’re looking north up Spadina at the intersection, with a tree-lined streetcar right-of-way heading up the middle of the street. You can also see the Mary Pickford Auditorium (on the left), the Bank of Hamilton (on the right), and some other buildings in the distance that still survive to this day:

Finally, you can see what the washroom looked like on the inside here. The signs on the stalls read “Please do not use closets as urinals” — an attempt to spare the toilet seats:

But even with warnings like that in place, many found the public washrooms distasteful. They soon went out of fashion. By the end of the 1930s, Queen & Spadina’s underground loo had been sealed off and filled in: sinks, stalls, urinals and all.

It was just the beginning of a long century of change, which has given us the Queen & Spadina of today: an intersection that would seem both familiar and strange to the Torontonians who passed through it a hundred years ago.

All photos from the Toronto Archives, except the washroom interior, the Queen streetcar, the streetcar work in 1922 (which are all from Library & Archives Canada) and the main image (from Wikipedia).

A version of this post originally appeared on the The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog. You can find more sources, links and related stories there.

2 comments

Somewhat related: I’ve had a theory for a while that “Lot Street” was originally Dundas Street–which along with Yonge Street were the first two streets carved out by Simcoe.

Old maps of Toronto show Dundas following the south bank of Garrison Creek to Ossington, then turning south to the Asylum where the CAMH campus is, and meeting up with Queen/Lot Street. Follow the story a little later when Dundas & Ossington became an intersection, and “Ossington” only heads north, while “Arthur Street” heads east, and Dundas goes south and north-west.

So when Simcoe was carving roads in the wilderness… Yonge headed north from the Bay, and became the first concessions street. And Dundas… petered off 3 miles to the west in the middle of nowhere? Makes more sense to me that Dundas and Lot Street were the same street, until the time came to carve the concession roads… and there was part of Lot street already carved up almost to the 2nd concession road west of Yonge (i.e. Dufferin). Made it very convenient for handing out estate parcels to the family compact.

So… that’s my “history of roads in Toronto” theory.

Can we request articles in this series? I’d love to know more about Arthur Street, and the North end of Trinity Bellwoods neighbourhood. My parents have told me that there was an old bridge at Crawford until the 1970s.

Richard, your comment —

Interesting theories on the concession roads, but not really right. I recommend my website THE TORONTO PARK LOT PROJECT at http://parklotproject.com — the map is designed to help the visualization of Toronto’s early geography (everything is clickable). Under the Map Controls (upper left) check the boxes for the Park Lots and for “Township of York and township (farm) lots”. The first concession line (later Lot Street, ultimately Queen Street) was surveyed in 1791 by Augustus Jones as part of his 11-township baseline survey, pre-Simcoe. In mid-1793, at the request of the new lieutenant-governor, John Graves Simcoe, Jones returned with Alexander Aitken to continue the survey of the Township of York north, just as far as the 4th Concession Line (today’s Eglinton Avenue). Yonge Street, by the way, started not at the Toronto Bay but at the first concession line (Queen Street), below that was a ravine, blocking the route south to the bay. I hope this is helpful.

To Adam Bunch, author of the article “A tour of Queen & Spadina a hundred years ago” which is on this webpage — congratulations, it’s a great read, and I love the photos!