The City of Toronto is criss-crossed with ravines and sunken railways, and the way we connect the city across these gaps is with bridges. The most famous is likely the Bloor Viaduct (mythologized in Michael Oondatje’s book In the Skin of a Lion), but many other more modern and prosaic ones create essential links that sew the city together – as long as you are in a motor vehicle, that is.

For pedestrians (and cyclists), in most cases the bridges are something very different – an obstacle, a fraught endurance test that they must overcome to get beyond their bit of Toronto “island” to another one. For pedestrians in particular, it’s an endurance test they often don’t bother even trying outside of a few of the shortest, most picturesque bridges near the centre of town. (I’m going to focus on walking in this post, but protected cycling routes across bridges are obviously also a priority).

These bridges have narrow sidewalks, and no barrier between the walker and the fast traffic beside them (on a couple of bridges a bike lane helps a little bit). Crossing them is a deeply unpleasant experience. It’s even worse in the winter, when snow is often plowed onto the sidewalk, leaving little or no space to walk safely. In the winter, these bridges are often completely inaccessible to people who move in wheelchairs or with other mobility devices, or who have visual impairments.

A few years ago, in preparation for the more frequent trains of the Union-Pearson Express, Metrolinx decided it needed to get rid of the level crossing at Strachan Avenue. The chosen solution was to drop the tracks down into an underpass, and build an overpass – a bridge – for Strachan Avenue. This bridge would be a key link between the extensive residential development in the eastern part of Liberty Village and King Street and the rest of the city. It would also be a key route southwards from the King Street and its streetcar to Exhibition Place and the waterfront.

The official documents describing the planned overpass note its importance as a connector for those on foot. The official City of Toronto study of the grade separation project (PDF) stated:

Strachan Avenue will evolve as the precinct’s main street. It will provide many connections into the surrounding neighbourhoods, and will become an even more important north/ south connection linking downtown with Lake Ontario … Over time, the street will be enhanced for pedestrians and cyclists who will enjoy bike lanes, broad sidewalks, street trees, ornamental plantings and decorative lighting.

Later, it concludes:

Strachan Avenue can become the lively, livable city street that it must if the surrounding area is to evolve into a truly viable new community … This solution will allow Strachan Avenue to reach its full potential as a gracious urban street that connects the City to the Waterfront and provides a good relationship to adjacent development and land uses.

And what kind of bridge was built to achieve these lofty city-building and connector goals? The bridge that ended up being built is … crappy. It has (unprotected) bike lanes for cyclists. But for pedestrians – on a prime walking route – there’s just a thoughtless, characterless cramped sidewalk, exposed to traffic. Fortunately the bridge is fairly short, but it certainly doesn’t invite crossing. It was clearly designed as if vehicles were the priority, and pedestrians were an afterthought.

Imagine if, instead, the sidewalks were wide and separated from the street by a barrier. Imagine if there was a lookout point so people could look towards the spectacular view of downtown from the middle of the bridge, or, on the other side, up the tracks towards Liberty Village. It would be appealing. People would want to walk south from King or north from Liberty Village along Strachan, even just to check out the bridge. All it would have needed was an extra metre of sidewalk and a low barrier separating it from traffic.

It’s true that there are now new pedestrian and cycling bridges not far on either side of the Strachan Avenue Overpass (the Fort York pedestrian and cycling bridge and the King-Liberty Pedestrian/Cycle Bridge), but they do not link up the core Strachan corridor, and for pedestrians in particular they would be significant detours. Just because there’s a pedestrian bridge somewhere nearby doesn’t mean that bridges with vehicular lanes shouldn’t also be attractive for walking.

In a city where we need to encourage walking – especially now that the pandemic has reinforced the value of being able to walk to more destinations near the area where we live – we need to have a completely different approach to how we conceive of bridges for vehicles. They need to be multi-modal by default, with space that is both safe and attractive for pedestrians and cyclists as well as vehicles. They need to be seen as infrastructure that will encourage people to walk across them – even as actual destinations for walking in themselves.

After all, inherent in most bridges is a view – in Toronto, often spectacular vistas over ravines. Bridges should be viewing platforms, places people want to walk across in order not just to get to the other side, but to enjoy the spectacular view that is best appreciated by those moving slowly on foot.

To achieve this goal, all new and rebuilt vehicular bridges in Toronto should, by policy, have:

- wide sidewalks – perhaps 3 metres wide

- a barrier separating the sidewalk from traffic (cycle lanes could perhaps be protected by this barrier too, just separated from the sidewalk by a curb)

- Look-out spots and benches where people can stop and look out at the view, or just rest

A bonus feature could include attractive safety railings, to make the walk more interesting. In some locations with sufficient volume of walkers, the bridge could even feature a stall for a vendor selling food or treats. Let’s make walking across a bridge an experience.

Waterfront Toronto will soon be building or rebuilding bridges around the Port Lands. Some of these will be walk/cycle bridges, but others will be for vehicles. If we want the Port Lands to be truly integrated with the city, these vehicular bridges need to also be walking bridges that create true connections across the water for people on foot, rather than being discouraging barriers to crossing.

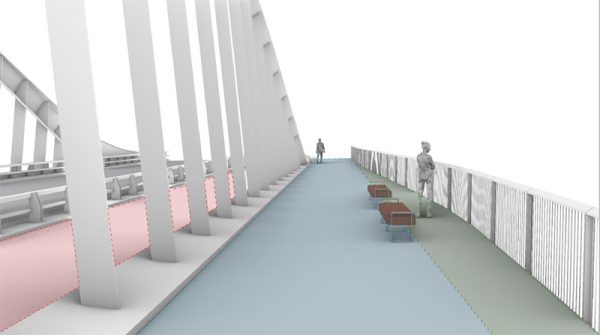

This summer, we learned that some of these bridges are already in the works. From the visualizations provided, it looks like they have taken these needs in mind, with wide sidewalks, some separation from vehicles, benches, decent railings, and spaces for looking out.

Another new bridge is now planned for Lake Shore East over the Don River – in the spring, on behalf of Walk Toronto, I wrote to the Infrastructure and Environment Committee (PDF) asking for the design to also incorporate that kind of vision. That bridge project will also be managed by Waterfront Toronto, and the recently revealed designs for their other bridges give a lot of hope that this one, too, will be an attractive place for people on foot.

But there are also other bridges all over the city that will need to be rebuilt someday, and perhaps the occasional new bridge will be needed in other parts of the city. The Port Lands is a showcase, and Waterfront Toronto has sometimes been groundbreaking in terms of its design, helped by a healthy budget, but we need that same vision to be used on bridges in parts of Toronto that aren’t such showcases and where Metrolinx, or the City, with its constrained budget, is in charge.

In her book How Paris Became Paris, Joan DeJean identifies the beginning of Paris as a modern city in the Pont Neuf, the bridge over the Seine completed in 1606. It was an entirely new kind of bridge, much wider than those in the past, and with a wide raised sidewalk on either side – the first in Europe since classical times. Most importantly, it had no buildings on it (common on other bridges at the time), and was provided with regular viewing platforms. It quickly became a destination, a place to stroll, to view, to see and be seen. And it greatly improved the connections between the parts of the city on the two banks of the river and accelerated development on both sides. Almost three centuries later, it was still a centre-point of the city, a favoured subject for Impressionist painters in their depictions of the city, with attention to the pedestrians strolling across it and looking out from its viewpoints.

That’s the kind of appeal and centrality we should be seeking for Toronto’s bridges. They should not just be utilitarian ferries for motor vehicles. In a city of ravines and railways, our bridges should be centre-points, destinations, and connectors that sew our city together for people on foot and on bikes.

Images: Pont Neuf, by Auguste Renoir; Google street view; Waterfront Toronto

4 comments

Plowing snow from roads onto sidewalks tells you everything you need to know about Toronto’s attitude toward pedestrians. How does an older or wheelchair bound person climb over the snowbanks regularly left at the corners? Lots of people shop and go to work by foot. Are they somehow inferior for not driving a car? They contribute to the economy like everyone else.

I once asked our councillor about remaking the footbridge to the lake from Roncy and King. The meeting was about the redesign of the intersection. I suggested a WIDE bridge with kiosks, seating and lookouts. Nope. Can’t afford it.

“Toronto the good enough” is not good enough. We certainly don’t have a mayor with vision. We could be so much better.

“Toronto the good enough” is not good enough.

Mayor Allan Lamport said “Toronto is tomorrow’s city. And, it always will be.”

When they build the Ontario Line, they will require a bridge next to the existing Leaside Bridge.

The current Leaside Bridge was originally designed for a future streetcar right-of-way down the middle. Instead they expanded the traffic lanes for the all-mighty automobile. The did add a bicycle lane, but in winter, snow windrows get dumped on it and even ending up on the narrow sidewalk.

With the Ontario Line Bridge, they should include a wide bicycle highway and pedestrian walkway with it.

This is a great article.

The Humber River near Dundas is a small creek, but the Dundas bridge is 100m high, scary and imposing. Trying to walk across, I feel I’m a pedestrian walking on the bank at a NASCAR race. I’ve never made it across on foot, and always give up in fear and frustration. It is a part of my neighborhood forbidden to me. There are so many bridges like this…

In Paris, bridges are human scale, charming, and inviting. Why do our bridges need on ramps, off ramps, and race car staightaways?

Underpasses could be a future topic. Each passage of the St. Clair / Scarlett underpass takes a lump from one’s soul.

I don’t see these bridges being improved, but I hope other human scale passages like the Humber pedestrian bridge near Lawrence being expanded, creating alternate pedestrian pathways.