The outdoors has been a solace for many of us as we struggle with restricted mobility and limited contact with others. It’s also one of the places where we can safely be with others. We need to be wary of seeing nature simply as a site for recreation, as resource, or as private property — something that we own or take from, or which is the backdrop to our daily activities. With more people spending time in urban parks and ravines, surrounding green spaces and provincial parks, it is important to recognize these as shared spaces. The coming together of people outside is a way to develop ecological literacy, have relationship with non-human creatures, create community, and engage with different knowledge systems. This entails responsibilities; to the soil, the water, the plants, animals, and to other people who occupy these places. Like all of Toronto, these are traditional territories for many Indigenous people. And they are places are rich sources of knowledge that we activate and practice by spending time outside. Artists in Outdoor School propose that we can learn together, with curiosity, humility, playfulness and generosity. — Amish Morrell

The process of developing Outdoor School as an exhibition for the Doris McCarthy Gallery (DMG) involved numerous trips to the University of Toronto Scarborough (UTSC) campus, not to do research in the libraries or have meetings at the gallery, but to explore the landscapes around the University with the artists and gallery staff; walking the steep hillsides below the main campus, the edges of the Highland Creek, and the swamps and meadows along the valley. Early one morning, with Ann MacDonald, Director of the DMG, I ran down the creek to Lake Ontario, following hidden footpaths and encountering several deer and a beaver that slapped its tail on the water when it heard us, the primordial-looking footprints of a heron and the remnants of campfires. When Ann returned to the gallery, I continued along the edge of the lake, looking for a trail that might lead up the Rouge River, cutting through suburbs, under Highway 401 where it passes over the valley, and through a swamp filled with stinging nettle that brushed against my legs, causing them to throb with pain. In this rugged river valley that runs through Scarborough, the only residents I encountered were several deer and signs of a muskrat living under the highway. On another research excursion, several of us identified dozens of species of mushrooms growing within a few hundred meters of the gallery. And on yet another, with forager Deirdre Fraser-Gudrunas, we literally ate our way along the valley, eating sorel, lamb’s quarters, wild grapes, and other edible plants that grow on the fringes of campus.

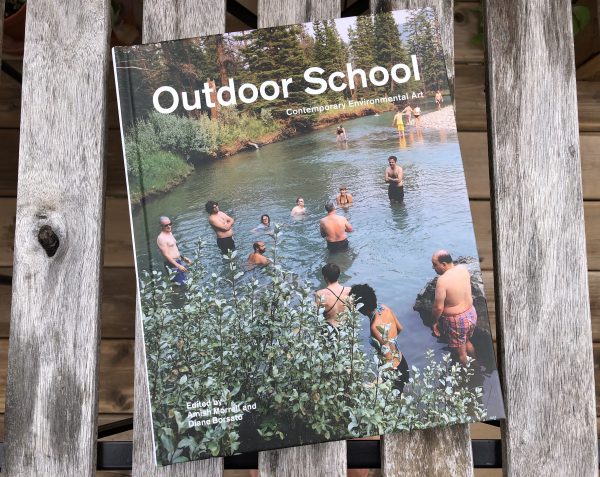

The concept of Outdoor School was to explore the geography and ecology of the universty’s campus with artists who use outdoor activities such as hiking, camping, running and forms of nature study as part of their practice. These took the form of a program of educational activities — workshops, performances and events that involved exploring these interstitial natural landscapes around the university — conducted both inside and outside of the art gallery. The gallery thus functioned as a meeting place, a classroom, and a place where tools, field guides, plants and other things being used or referenced could be displayed. Rather than exclusively encountering images or display objects, through more passive modes of reception, viewers were invited to engage these landscapes through artist-led activities that involved movement, study, and reflection, and which invoked a fullness of sense and imagination.

While this show presented ways of learning about urban nature, and the interstitial wild spaces within the city, it was also about the wild spaces within artistic and cultural practice itself, involving artists whose work often doesn’t neatly fit into conventional modes of gallery presentation. This is implicitly the case with social practice based work, such as that of Helen Reed and Hannah Jickling. And it is also the case with other artists including Deirdre Fraser-Gudrunas/Vibrant Matter, who makes her livelihood as a forager, but who offered a complex aesthetic and philosophical rethinking of how we relate to plants. Similarly, Ayumi Goto’s running-based artworks presented a reimagining of what it means to run. Jay White took the popular activity of hiking and camping, but instead of exploring a designated wilderness area such as Algonquin Park, he camped in the marginal natural spaces of Scarborough, mirroring other non-human animals that live within the city. Jamie Ross’ work delved into countercultural ritual, using it to structure an expanded understanding of the land and our physical and spiritual belonging within it, creating place-based workshops and ritual performances that draw from the practices of the Radical Faeries, a rural anarchist genderqueer movement that has been around since the late 1970s. While these activities engage and produce nature as a cultural phenomenon, and play with the tension between the urban and the wild, as art practices they inhabit a different kind of wild zone, in that they refuse the disciplinary borders between art practice and everyday cultural and countercultural activity. Staging these practices within an art context has a dialectical function: First, it allows us to rethink activities such as running, camping, and nature study by enlisting artists in reconfiguring them ideologically and aesthetically, activating their critical potential. And second, by bringing these activities into the gallery’s program as artistic forms, we alter core institutional assumptions about what constitutes an artwork, challenging how it is often separated from its discursive, embedded social function. In this show, the mutability of exhibited objects and programmed activities sought to transform the role of the exhibition in relation to both its audience and its geographical and ecological context.

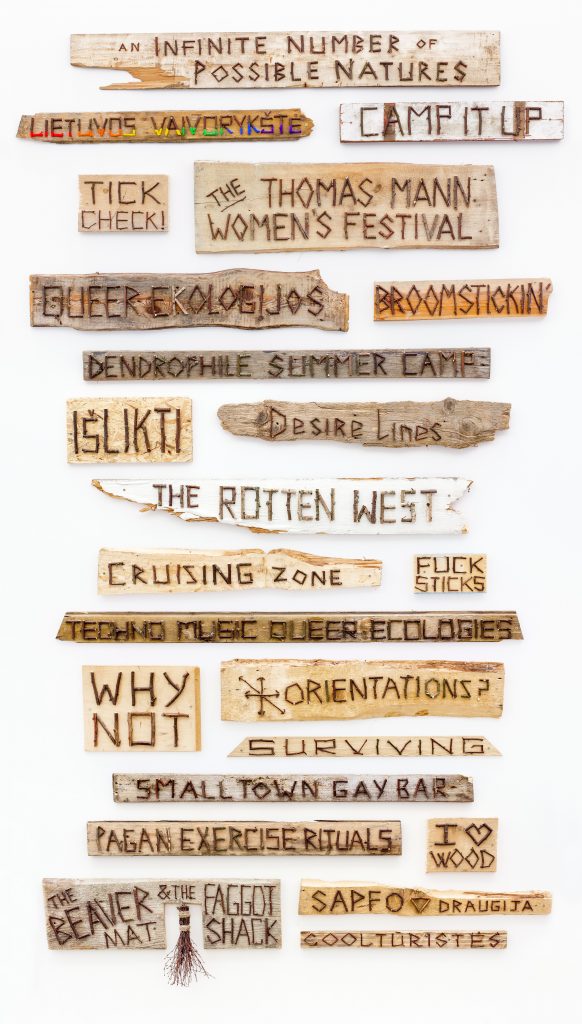

While Outdoor School engaged the wild interstices between artistic practice and counterculture, and expanded what an exhibition can do, it also addressed what might constitute a queer approach to nature, unsettling, and creating an alternative to the ideologies that often structure our experience of the outdoors. Hannah Jickling and Helen Reed strategically eschewed the gear-centric logos of outdoor recreation that position nature as a terra nullius that requires Gore Tex outerwear, freeze-dried dinners and a Garmin GPS device, and emphasizes performance, fitness and accomplishment. In The Beaver Matt and the Fag(g)ot Shack, they took DC Beard’s plans for a shack made out of bundles of sticks, outlined in a book he wrote in 1914 for Boy Scouts, recreating it not for quasi-militaristic young men, but as a small-town gay bar, proposing an alternative, cultural and sexual identity located in the outdoors. This piece, and other documents of their social-practice based artworks, point towards a critical methodology that is deeply queer, exposing and disrupting ideologies of the natural.

If Jickling and Reed’s work pointed towards expanded conceptions of outdoor recreation and education, documenting activities held in places far from campus, the rest of this exhibition put these ideas into practice through public events that use the gallery as an anchor for exploring the landscape around the university. In her installation, Deirdre Fraser-Gudrunas/Vibrant Matter stored and displayed field guides, dried plants, and harvesting baskets that she then used in plant identification workshops, where participants sat at Maggie Groats’s When Fences Turn into Tables and recorded their sensory experiences of plants they found on campus. Grounded in philosopher Jane Bennett’s idea of “vibrant matter” — that plants and other material, non-human objects exert a vital force on the things around them, and thus have agency, her workshops require careful observation, focusing on experiential knowledge, using this to create a local taxonomy and alternative knowledge system that is based in the senses and the imagination. 1 (see endnotes below)

Similarly, Ayumi Goto, a Japanese-Canadian artist, cultural organizer and runner, used the gallery to display her running outfit, which she used during a performance held during the exhibition. Some of her past works were formed in dialogue with both artists and activists, including Cheryl L’Hirondelle, whose songs she listened to as she ran, and the Nishiyuu Walkers, running 1,600 kilometres on traditional Indigenous territories, mirroring their journey from Northern Quebec to Ottawa in 2013, as part of Idle No More. Over four days during Outdoor School, she ran various routes near the UTSC campus, attending to sites of charged cultural or social significance. Her outfit consisted of a white Japanese kimono undergarment that registered the traces of her exertion, wear and tear from her surroundings and all that clung to her clothing, and a small bell that rang as her pace increased, acting as a cue for her to pause for a moment of quiet reflection. Referencing the Japanese ethical concept of Rinrigaku, Goto uses running as a vehicle for a performance art practice that its audience can experience by running with her, witnessing and registering the landscape through their bodies. In this work she shifted running from being simply about leisure, performance, fitness and personal development, to an activity that is about knowledge and politics, engaging cultural memory and recognizing others who occupy the land through a daily physical practice.

In Coyote Walk, an installation and performance, Jay White engaged crucial tensions between the visible and the non-visible and human and non-human animals. In his installation, placed among a series of radio tracking devices used to monitor various forms of wildlife, was a mirror in which one can see their own reflection. If one went behind the wall on which the devices are mounted, and stood among the boulders and stumps used to keep it upright, they could look through the back of this one-way mirror from the position of the human animal, trying not be seen. Through his performance of Coyote Walk, White extended these ideas even further, spending four days hiking and camping in the interstitial landscapes of Scarborough, mirroring the patterns of urban coyotes, resting in sheltered spots during the day and travelling at night. Throughout the walk he carried a GPS device that posted his location to a website, so that audience members could track his movement. Rather than intervene in the landscape, he followed a script that dictated that he avoid human contact, limit his movement to natural areas, and, as much as possible, make himself invisible. As a work of performance art, Coyote Walk employed a feat of physical and mental endurance, carried through to its completion, to allow his surroundings to radically transform his awareness of the landscape and his place within it, as well as that of his audience.

The use of an alternative set of instructions for moving through urban wild spaces is a strategy also used by other artists who appeared in the show. They created specific scripts or forms — a guided walk, a ritual, a workshop, or a running route — that allowed us to access forces and histories that are not visible, that are outside of conventionally inscribed frames of reference. Jamie Ross induced a hypnotic trance in A Script of Desire to access a secret script that he developed as a teenager. Similarly, in the workshops that he led for Outdoor School, he drew from pagan countercultural practices and the traditions of the Radical Faeries to develop new rituals that deepen our relationship with our natural surroundings. Grounded in careful attention to the specific properties and uses of plants, and the histories of the places in which they grow, he used pre-existing ritual forms so that participants could explore how their natural surroundings affect their consciousness and imagination.

One of the most jarring aspects of the landscape around UTSC is the contrast between the landscapes along the rivers that cut through Scarborough, places that writer Anne Michaels called “the city’s sunken rooms of green sunlight,” and the vast tracts of post-war suburbs, ten-lane highways, and massive hydro corridors that span between them. 2 As I explored the Highland Creek, passing under the expressways and rail lines that stand high above the valley, I couldn’t help but think of a popular Situationist slogan, from the student uprisings of 1968, that spoke to the idea of reclaiming space itself from the forces of capitalism, finding an alternate reality beneath the bureaucracy and order of the city. This slogan, Sous les pavés, la plage! translates into “Under the Street, the Beach!” 3 But here it might be reworded as “Under the Freeway, a Forest!” In between, around, and beneath the streets and houses and urban infrastructure through which people and things move, are vestiges of landscapes that long precede the city itself; interstitial wild spaces that we rarely encounter. These consist of rivers and streams that wind their way through the city, sometimes disappearing underground, wide sections of forest, and forgotten urban infrastructure where nature endures. Almost invisible to us, as we carry out our lives, it connects us to ecological processes more vast and enduring than the city itself.

For many of the artists in this show, their work involved trespassing in one way or another, and often invoked the question of whose land we’re on. This region around Toronto has been occupied continuously for about 11,000 years, by eight distinct Indigenous peoples in the millennium preceding colonization, and more recently by the Mississaugas. In the 1640s, an estimated 65,000 Anishinaabe people lived in the areas around Toronto, in a landscape that was radically different from the urban sprawl that exists today. Managed by the Anishinaabe, the forests were vast and park-like, filled with fish, game and plants that were used for a range of uses including food, shelter, medicine, and ceremony. Rivers such as Highland Creek and the Rouge were important food sources and thoroughfares, and places where people lived for thousands of years prior to colonization. 4 During the past several hundred years, however, the landscape has undergone its most radical transformation, subdivided and eventually filled in with shopping plazas, high-rise apartment buildings and suburban lots. Yet rivers such as the Highland Creek and the Rouge still flow through it, and there are spots along them where one can glimpse a sense of how it might have appeared centuries earlier. Accessing these places sometimes involves going beyond the paved trails of urban parks, ignoring signs warning of poison ivy or black legged ticks, or those that demarcate private property. There are unmarked paths between property lines that lead into the ravines, neglected spaces alongside or underneath the highways, conservation easements and abandoned industrial lands. Accessing these spaces often requires tiny acts of trespassing; a minor crime compared to the wholesale expropriation of this land from its original occupants.

Time spent in these places invokes the presence of others, and sometimes a sense of the significance these places might hold for them. In the ravines we found forests of hundred-year-old pine and oak, dropped deer antlers, and places where people camped along the river. We also found pieces of red satin embroidered with gold thread, ceremonial packets of what looked like cremated remains, washed up along the riverbank, and we found condom wrappers in a sun-dappled stand of pine trees.

Later, when using First Story, an app that geotags sites of First Nations history and presence in Toronto, I saw that just five kilometres further upstream was Tabor Hill Ossuary, an Iroquois burial mound containing the remains of more than 500 people, dating from 1,250 years ago, discovered during excavation for a housing development in the 1950s. Traces such as these gesture towards the many others who have occupied these places, and those who continue to live there. 5

The exhibition invited its audience to join the artists in developing a literacy of the natural spaces around the University of Toronto Scarborough. With them, we explored how these places themselves register forms of knowledge — through plants, animals, and ecosystems. Entry into these spaces often involves transgression, whether it be of social norms, disciplinary boundaries or private property. This was made explicit in Maggie Groat’s When Fences Turn into Tables, a functional table made from pieces of wood she discretely removed from fences and alleys in Toronto, dismantling the artifices of private space and reassembling them in a form around which a public could be constituted. In this show the table hosted an audience that gathered to identify mushrooms, describe their sensory experience of plants, or create knot spells that encode their desires in natural materials. Along with the other works in the show, it offered a model for an alternative public sphere — a school of the outdoors — for artists, trespassers, foragers, agoraphiles, and anyone else who wishes to gather here, in the forest that winds its way under the freeway.

ENDNOTES

- Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter (Durham: Duke UP, 2010).

- Anne Michaels, Fugitive Pieces (Toronto: McLelland & Stewart, 1996), Thanks to Jamie Ross for pointing out this reference.

- McKenzie Wark, The Beach Beneath the Street: The Everyday Life and Glorious Times of the Situationist International (London: Verso, 2011).

- Due to its temperate climate and geographical location, this region is described by historians as having been comparable to the Mediterranean in terms of extent of trade and cultural activity. Rodney Bobiwash, “The History of Native People in the Toronto Area, An Introduction,” in Sanderson, F. and Howard- Bobiwash, H. (eds.), The Meeting Place: Aboriginal Life in Toronto (Toronto: Native Canadian Centre), 5-24.

- The First Story Toronto App can be downloaded from itunes and found at: https://firststoryblog.wordpress.