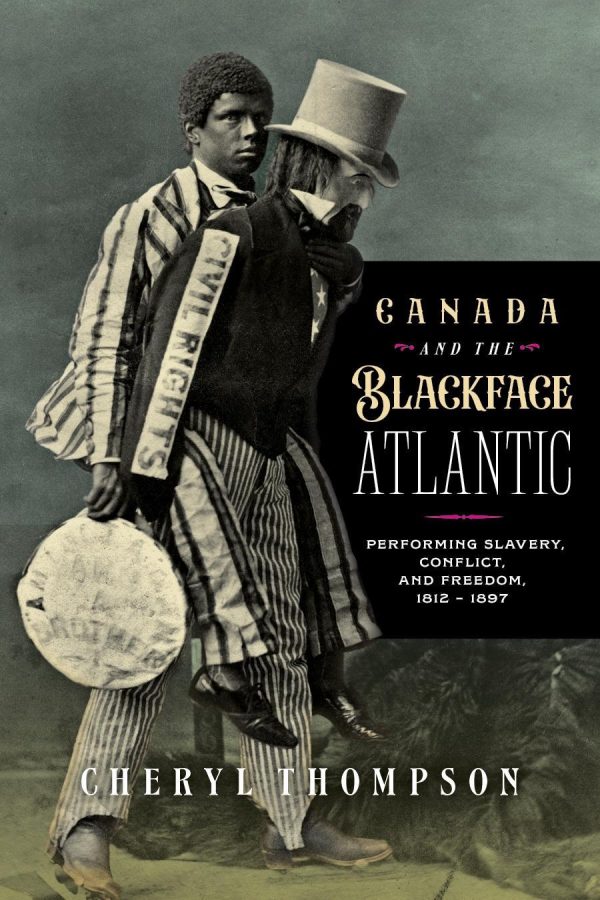

Excerpted with permission from Canada and the Blackface Atlantic, published in April 2025 by Wilfrid Laurier Press. Thompson, a Toronto Metropolitan University associate professor in Performance and a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair, specializes in 19th century Black history, visual and performance culture. Canada and the Blackface Atlantic traces the rise of Canadian blackface, including the country’s first stages. It outlines the minstrel troupes, jubilee choirs and concert singers who performed to audiences on the same stages, and ultimately argues that the theatre helped to create racial and gender stereotypes while also challenging ideas about slavery and freedom.

When New York-born Thomas Dartmouth (T.D.) “Daddy” Rice (1808–60) performed “Jump, Jim Crow” for the first time in 1830, his comic “plantation darky” slave character, who would be called Jim Crow, was brought into the popular theatre.

At the end of the 1830s, the circus (sometimes called a “menagerie”) was the first to bring blackface clowns to Canada. A June 1840, article in the British Colonist, a short-lived newspaper published out of Toronto, referenced a performer who sang and danced “á la Jim Crow.”

While “Negro songs and dances” had been performed by White men in blackface at circuses and in variety “olios” since the 1820s, and the circus was where the vast majority of minstrelsy’s first popular acts got their start, Canada did not have a circus company; instead, it relied upon travelling circuses, which had been touring the country since the late-eighteenth century.

By the 1840s, Toronto’s Black population was significantly engaged politically, and they demanded these kinds of performances be forbidden in the city. Members of the community petitioned the city’s mayors to not grant licences to circuses and menageries: Mayor John Powell (1809–81) in 1840, his successor George Munro (1801–78), in 1841, and Henry Sherwood (1807–55) during his tenure in 1842 and 1843. All failed to take the Black community seriously enough to act on their petition, which decried that “certain acts, and songs, such as Jim Crow and what they call other Negro Characters” be banned from the city’s stages.

As early as 1809, there was a performance at York (Toronto) by American companies, but it was not until 1834 that Toronto had its first real theatre, a converted Wesleyan church. In 1846, Toronto’s first designated theatre, the Toronto Lyceum opened, and it attracted both amateur and touring professional groups for two seasons until the government took the building back for other purposes; in 1848, a new permanent theatre, the Royal Lyceum, was built.

The Lyceum was the first in Toronto to be erected for exclusive theatre use, the first proper theatre in town, and, from all accounts, the first proper theatre in Ontario. Histories differ on the matter of an opening date, although according to The Globe at the time, the theatre opened on December 28, 1848. A blackface troupe calling itself the Ethiopian Harmonists was the first to draw large crowds at the Royal Lyceum in 1849.

As the city’s first purpose-built theatre, the Royal Lyceum was financed by wealthy landowner John Ritchey, and it was significant not only because it was Toronto’s first opera house, but because it offered more than opera; it featured plays, groups of actors, strolling musicians, soloists, and elocutionists. The Royal Lyceum also ushered in a new era of professional theatre in the city as programs ranging from Shakespeare to blackface were all staged there, with no reports of rebellion or disruptions ….

Toronto audiences were not yet prepared to support a regular professional theatre, and despite dreams of seeing the city become the centre of a circuit, it remained in its embryonic condition in the 1840s. At the same time, musical and choral societies began to form around the region as well as public and masonic halls.

Significantly, the business and political class in Upper and Lower Canada (Ontario and Quebec after 1871) had long established ties to Atlantic slavery; several prominent leaders owned and sold slaves. Upper Canada-born Samuel Jarvis (1792–1857), for example, was part of a slaveholding family. Jarvis fought in the War of 1812 and was part of Toronto’s political class when the city was incorporated alongside his father, American-born William Jarvis (1756–1817), a militiaman and member of early local governments in York.

The Jarvises owned at least six Black slaves, even as the law in Upper Canada was decidedly anti-slavery, according to John Ross Robertson’s (1841–1918) book ‘Landmarks of Toronto,’ written in 1894. Peter Russell (1733–1808), an Ireland-born military officer in the Revolutionary War and a government official, politician, and judge in Upper Canada, was also a slaveholder. Of the believed-to-be 15 enslaved persons living in York in the early nineteenth century, the majority were owned by Russell and Jarvis, who by all accounts were corrupt and unsavoury officials.

Even though a 1793 Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada was the first legislation in the British colonies to restrict the slave trade, as a gradual abolition bill it did not end slavery outright. This meant existing slaveholder property rights remained, and children of enslaved women were only free after the age of 25 (their own children would then be considered legally born free).

Understanding the timeline for when Canada’s theatre houses were built is important to this discussion of blackface. It illustrates the significance of theatre in the country’s formidable years of development, and how central racial politics were to entertainment culture in an era of significant change and conflict. As Black people begin to imagine their own emancipation by migrating north to Canada, blackface minstrelsy reimagined plantation slavery for popular audiences.

While the ruling White political classes and newly-arrived White immigrants had the privilege of, and access to, land ownership through the assistance of anti-slavery societies (the first founded across the Atlantic at the end of the eighteenth century) Black people were able to establish free settlements across Canada West (Ontario after 1841), though few were able to become landowners. This convergence of events, people, and varying degrees of enfranchisement took place at the exact moment blackface minstrelsy, the railway, and newspapers emerged as key institutions in the modernization of cities across North America.

Amateur theatre such as the Gentlemen Amateurs of Toronto, which inaugurated a lengthy season in December 1846, the Amateur Theatre Society which performed in 1843 and then again in 1846, and the Toronto Coloured Young Men’s Amateur Theatrical Society, which rented the Royal Lyceum for three nights in 1849, were undoubtedly attuned to Atlantic world theatre. Most notably, the Coloured Young Men’s Amateur Theatrical Society performed Venice Preserved by Thomas Otway (1652–85) along with selected scenes from Shakespeare, according to an advertisement in the Toronto-Mirror’ on February 9, 1849 that promoted their three-night run (February 20, 21, and 22 of the same year ) at the city’s only theatre.

By all accounts, this is the first known performance by an all-Black theatre company in Canada. There is no question that the Toronto Coloured Young Men’s Amateur Theatrical Society’s performance was inspired by the city’s rejection of the Black community’s petition to stop public appearances of blackface menageries a few years prior. It is also possible that they were bolstered by the theatrical success of other Black performers across the Atlantic.

Providence, Rhode Island-born William Henry Lane (1825–52/53), also known as “Master Juba,” was the first Black actor and dancer to perform in blackface on White stages in the US and England, and New York-born actor Ira Aldridge (1807–67), who often performed in his “natural skin” on some of the same stages on the same night as White minstrel acts. Even as he wore blackface (by force) Lane, like Aldridge, challenged White audiences’ perceptions about Blackness and notions of freedom.

By the mid-1850s, Canada West was firmly established as a theatrical centre for minstrel shows. Audiences were well-invested in the stories and caricatures that sought to retell histories of the Atlantic world in ways that did not require Canadians to reflect on their own racial attitudes, even as racial hostilities were on the rise south of the border.

Cheryl Thompson is an Associate Professor of Performance at Toronto Metropolitan University. She is also author of Uncle: Race, Nostalgia and the Politics of Loyalty (2021), and Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture (2019). Follow her on X @DrCherylT.