Spacing contributor Ian Malczewski spent September 30 – October 3 in Niagara Falls at a joint conference held by the Ontario Professional Planners Institute and the Canadian Institute of Planners. He is sharing some of the lessons he learned there and reflecting on their implications on public space, livability, and sustainability in cities.

The first session I attended at the OPPI / CIP conference was called LEED-ing by Design. The purpose of this workshop was to educate planners about Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design – Neighbourhood Development (LEED ND), which, according to the United States Green Building Council (USGBC), aims to “integrate the principles of smart growth, urbanism and green building into the first national system for neighborhood design.†Knowing a bit about LEED Building certification (as well as some of its critiques), I was curious to see what design elements would apply at the neighbourhood scale.

LEED ND (currently in a pilot phase) offers credits across a number of areas of neighbourhood design, including, “Smart Location and Linkage,†“Neighbourhood Pattern and Design,†“Green Infrastructure and Buildings,†and “Innovation and Design Process.†Provided a development meets certain prerequisites (such as developing in or near public transportation corridors), these credits can be put towards applying for LEED certification. While this process helps improve developers’ bottom line by helping them sell units more quickly, it also creates harmonized guidelines to build the kinds of people-scaled neighbourhoods we got away from in the late half of the twentieth century.

I was encouraged to see the public realm was prominent in these guidelines, with developments earning points for providing public spaces within walking distance of people’s homes. Developments can also earn credits for encouraging “connected and open communities, “mixed-use neighbourhood centres,†“bicycle network and storage,†and “local food production.†The full check list (PDF) is available from the USGBC.

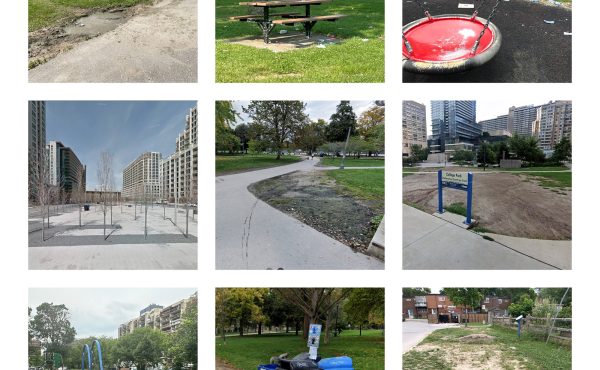

In addition to contextualizing neighbourhood design in Ontario’s current land use policy framework, the panel presented two Canadian projects participating in the LEED ND pilot program, including the Currie Barracks development in Calgary and a handful from Toronto’s waterfront (the East Bayfront, West Don Lands, and North Keating, all of which have achieved Stage 1 LEED ND Gold certification). The Waterfront Toronto designed neighbourhoods in particular impressed me, with their developments placing public space at the heart of creating sustainable and livable neighbourhoods (more about this in future post).

While I left the workshop agreeing that LEED ND guidelines could help create livable and sustainable communities, I did have one nitpick: the certification only applies to new-build redevelopment projects. Careful redevelopment of greyfields, brownfields, and greenfields is an important component to city-building, but sustainable urban development discussions increasingly focus on retrofitting existing communities rather than building new ones (see the current issue of Spacing for more discussion about these issues). As I understand it, LEED ND certification only applies to redevelopment and revitalization projects rather than retrofits.

To its credit, the USGBC did eventually adapt its LEED Buildings certification to include an accreditation for existing buildings, and if that principle shifts to neighbourhoods then LEED ND could help encourage neighbourhood change in a broader context. So while LEED might not yet offer a picture-perfect recipe for transforming into sustainable and livable places, it does take a step in the right direction.

Image courtesy of Waterfront Toronto.

5 comments

LEED ND vs Planning legislation in Ontario. Is it a parallel system of land use planning?

Mike:

There are some similarities. Ontario’s current planning policies encourage the creation of pedestrian scale, mixed use communities, and suggest many of the same design elements as LEED. There is no formal connection between the two, but they have the same spirit.

The Provincial Policy Statement might be a good place to look for other parallels:

http://www.mah.gov.on.ca/Page1485.aspx

Yes, there are definitely some areas that the USGBC needs to think about. This is why LEED-ND is in its pilot phase. I’m actually really excited for LEED-ND to be fully developed. I think it’s a great idea. LEED is not perfect, yet, but as you said, it’s a step in the right direction. It will only get better with time.

LEED is a witch’s brew of weights and biases that try to balance multiple goals and financial realities. In LEED Core/Shell and LEED New Building, not nearly enough credit is given for brownfields, alternative energy and transportation proximity compared to the points you can rack up for energy monitoring, localized construction materials, staff training and other items that frankly do not have nearly the impact in the long run. What was your take on the point weightings that were applied in ND?

iSkyscraper –

In the workshop I did, the weightings hadn’t been assigned yet, presumably because it’s still in a pilot phase (they may have explicitly told us this, actually, but I may have missed it during one of the conversations at my table).

I agree that the weighting is where the LEED certification usually succeeds or fails. Should remediating brownfields be worth as much as developing near transit, especially if the neighbourhood is already located downtown and is piggy-backing on an already existing transit network? It’s a complex calculus for sure…