By Erick Villagomez, re:place magazine

By Erick Villagomez, re:place magazine

Cities, by their very nature, are always in a state of change. Responding to the myriad of internal and external forces placed upon them, they ebb and flow continually. At certain times throughout history, the profound changes have shaken the foundation of cities and the human made systems that create them – many of which decline as a result.

We are living in such a time: as radical environmental, social and economic shifts have driven us to question the way we have organized and planned our urban centres for the past century. Cities are currently developing and changing at a rate exponentially faster than planners’ attempts to shape them. Economic, political and environmental circumstances are changing so quickly that by the time a plan is realized, it is often already obsolete. As we have readily witnessed locally, a sudden change in political leadership or economics can fundamentally alter the assumptions and objectives of a project or planning initiative.

Within this context, typical planning processes and bureaucratic structures – indeed, the urban planning profession as a whole is quickly losing relevance. Unless we rethink the fundamental principles and systems governing urban planning in accordance with this climate of rapid change, it seems inevitable that this vocation will continue its decline into obsolesence. Petaluma, California’s recent termination of its entire planning department points to how dispensable the profession currently is and forecasts a very real potential future for planners across the nation.

The young profession of urban planning had noble beginnings just under a century ago. In Urbanization, Paul Knox and Linda McCarthy discuss how the planning profession arose in response to health, social and natural crises – as epidemics, riots and floods inundated cities and sparked interest in institutionalizing municipal control measures. As was the spirit of the time, planning was built upon Marxist ideals as well as moral, social, and philanthropic values of bettering the conditions of urban citizens – well-intentioned sentiments that continue today.

Importantly, through focusing on the health and safety of urban citizens, planning was also seen as a means to mitigate the adverse effects of capitalism – speculation, in particular – on the built landscape. With this in mind, several significant control measures were established. The most significant was the Zoning Law – first introduced in New York in 1916 – whereby an imaginary “building envelope” describing the outline of maximum allowable construction was specified for a building lot or block to ensure light and air

This act solidified planning as a design project, over and above a legal document. And although zoning had its roots in social well-being, these mechanisms quickly evolved into practices that served other purposes under the guise of the public good – particularly the maintenance of property values for the wealthy. Locally, Vancouver’s RS-5 zoning bylaw focused in and around Shaughnessy that is still intent on “maintaining the existing single family character” of their respective areas and “compatible” housing developments is the most blatant example of this (a brief discussion of the motivations behind the creation of the RS-5 bylaw can be found here).

As such, zoning practices extended beyond dense city centres, where light and air concerns were paramount, into outlying areas where they were used to ensure low-density, freestanding single-family neighbourhoods through mechanisms such as building setbacks. This was, in turn, bundled with a permitting process.

This was interconnected with racial biases, the growth of the automobile, and simplistic notions of urban systems that segregated different uses – residential, commercial, industrial, etc – into different parts of the city. All of which was bundled into larger bureaucratic processes of permitting, guideline development, and internal reviews. As such, it has been strongly argued that urban planning – counter to its noble initial intentions – has played one of the most significant roles in humankind’s single most extensive urbicidal acts.

This brings us to the present, where the detrimental social and ecological implications of these early decisions have been made clearly evident while, simultaneously, the structure and practices these employed by the urban planning profession – based on these early assumptions – have been institutionalized and solidified to the point that change is increasingly difficult, even internally.

Historically, cities coped with radical political, economic and environmental shifts through rapid bottom-up transformations to the built fabric that was allowed through flexible (often minimal) top-down control mechanisms. Thus, for example, former urban farm lots and houses could freely evolve into higher density house types in response to growth pressures. Examples of this abound and are responsible for the creation of well-known cities like London, Rome and Athens and even early Vancouver.

But currently, such changes are held captive by our obsolete, slow-moving urban planning practices. An important effect of contemporary urban planning that is often not discussed within the field is that, in attempting to control all aspects of city development, the impossible task of predicting and responding to rapid, unforeseen change through built form has been placed on the shoulders of a handful of people who have neither the education (no one profession does) or power at their disposal to make informed decisions at the rate required to do so.

In this respect, urban development has been, and continues to be primarily reactionary instead of proactive – attempting to develop in comprehensive wholes instead of realizable increments that are quickly implemented and emphasizing organization instead of augmentation. In Vancouver, for example, secondary suites were illegally being used for over 10 years(!) before the City formally made their creation legitimate. Similarly, it will be four years of report writing, council approvals, and internal bantering since the initiation of EcoDensity that laneway housing will (hopefully) be legalized – the first of several initial actions, yet to be fully realized.

Consequently – and to the City’s credit – four years is outright swift within the typical bureaucratic timescale. However, it is also ironic that it was urban planning that made laneway housing and secondary suites illegal decades ago. So these progressive “achievements” are really untangling the mess the profession created in the first place, and bringing us back to the point we should have been over 50 years past.

That said, given the rate of explosive change in virtually every facet of society, the time taken for planning measures to be created and implemented should be considered effectively unresponsive. From accelerating urbanization, to economic hemorrhaging and unprecedented climate change effects in countries the world over – Australia being the most recent casualty – it seems almost comedic that urban planning as currently practiced can viably foresee even 5 years ahead, let alone 50 years in advance. Or respond to any unpredicted forces in a timely manner amidst their tedious bureaucratic operations. Vancouver is one of the worst, with respect to the latter. So much so, that the prolonged and poorly streamlined development processes of the City attained special recognition within John Punter’s The Vancouver Achievement as well as Andres Duany’s lecture when he last visited.

So what does this mean to for urban planning?

The lack of sufficient time to plan brings with it an atmosphere of higher risk. If planning is to remain relevant – economically, environmentally, socially, and politically – amidst the instability of the future, it must to be rethought in a manner that assumes risk and does not avoid it. Instead of simplistically putting all its eggs into a future based on past and present trends, urban planning must provide sufficient looseness within future scenarios while attempting to tilt the odds in favor of certain directions.

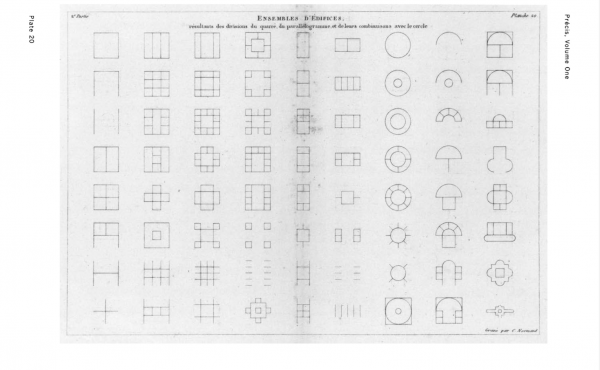

Cities must be strategized not just in terms of how they are intended to work currently, but also how else they might work under extremely different (unforeseen and inconceivable) circumstances. As such, similar to well-designed software, urban plans must posses a variety of alternative organizational patterns as opposed to not the standard one.

Furthermore, urban planning must balance top-down and bottom-up thinking as a means of creating a variety of plans of equal value. This will necessarily be multi-disciplinary. However, the versatility created – like diversified stock portfolios – will allow a given design strategy to spread the risk and decrease its susceptibility to failure or obsolescence due to change in conditions. Additionally, it will recognize the emergent intelligence of its citizens to give appropriate physical form to the pressures being placed on them – to be refined, not created, by “higher-level” professionals.

Uncharacteristically, urban planning must also be opportunistic – encouraging piece-meal processes that operate on the as-needed basis required by a constantly changing present. Within this context, latent value and potential futures must be actively “discovered” through the careful observation of existing settlement patterns – from individual buildings to the larger city scale.

Lastly, and very importantly, planning departments must be re-organized to allow for rapid implementation and experimentation. This is intimately related to fostering creativity and innovation, and acting on it rapidly: measures currently not a part of typical urban planning regimes. Similar to successful businesses – like Nike who, in the 1980’s formed product specific multi-disciplinary teams called “speed groups” to by-pass their internal bureaucracy and rapidly deliver the “latest” styles to consumers – planning must engineer an internal infrastructure that permits the transformation of our cities within compressed times frames.

All this points to a new form of open-source planning. One that differs drastically from the current closed and centralized model of urban planning and integrates the older, bottom-up flexibility of past cities with more specific top-down methods based on the handful of positive lessons we’ve learned within the past century. It is a model that must strive to make fewer, but more intelligent decisions.

It’s worth saying, as well, that open source planning goes beyond the community engagement workshops and urban design panels currently being practiced. While these are definitely a step in the right direction, they are still trapped within the larger outdated model of urban planning described above, and as a result are not being fully mined for the creative potential that this inclusiveness brings.

Ultimately, this will lead to the radical transformation of the urban planning profession as we know it – the death of old obsolete roles /processes, birth of new ones and reformulation of others. With this in mind, it makes sense that Vancouver – a city known for its urban planning experimentation – take the lead in addressing the biggest culprit holding us back from meaningful and much-needed change: the fundamental structure and processes of urban planning, itself.

And this seems fitting on a higher level as well since courageously this direction – valiantly sacrificing themselves to the unknown for the greater good of society – will be to bring the profession back to the virtuous roots from which it flourished. Roots that have long since eroded after decades of cultural weathering.

***

Erick Villagomez is one of the founding editors at re:place. He is also an educator, independent researcher and designer with academic and professional interests in the human settlements at all scales. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places.