With the recent reopening of the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, along with a newly renovated Art Gallery of Alberta in Edmonton, re:place contributor Sean Ruthen ponders the role of the art gallery in the city, as well as the future of our own Vancouver Art Gallery here in the Lower Mainland.

Photos and text by Sean Ruthen

In April of last year, people in Toronto lined up for three consecutive days to be the first to see the newly reopened Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO). The seven year project was the vision of the late Kenneth Thompson, a prominent Toronto businessman and gallery supporter, as well as gallery CEO Matthew Teitelbaum and architect Frank Gehry, and with the cutting of the ribbon, the $276 million renovation added nearly one hundred thousand square feet to this 100 year old gallery. With a similar project currently set to open in Edmonton – the Art Gallery of Alberta (AGA) underwent a two year renovation by architect Randall Stout (coincidentally a former architect at Frank Gehry’s office), adding 85,000 square feet to their existing gallery for the much more modest sum of $88 million – it would seem that many cities across Canada are renovating their ‘cultural infrastructure’, as we here in Vancouver will likewise soon see a major renovation of our art gallery.

But it is without question Toronto that has been the tour de force in its unbridled drive to upgrade its civic infrastructure. In January 2006, I wrote a short essay on some then new buildings underway in Toronto, including Daniel Libeskind‘s ROM and Frank Gehry’s AGO additions. I had just visited Will Alsop’s new OCAD expansion, and was astonished to learn how this was the first of about eight or nine other projects that were underway in the city at that time, including a new performing arts centre, a refurbished ballet school, a museum of ceramic arts, and a good dusting off of the old city hall. Even more projects included a new Times Square-like plaza – Dundas Square – at the intersection of Dundas St. and Yonge St., as well additions to the University of Toronto.

With the doors again open at the AGO, it is perhaps an ideal moment to survey the results of this flurry of activity in Canada’s largest other-English speaking city, as well as what it means for the identity of that city. We, in the west, have also seen quite a few new buildings built, with a long construction boom that saw a new trade and convention centre constructed, as well as a new LEED friendly community for the Olympic athletes, to name but two projects of several. This has been an unprecedented time for civic and cultural building in both Canada’s east and west at the same time, much as it has been for the rest of the world, including Beijing’s three-ring architectural circus for their summer Olympics, the newly opened CityCenter project in Las Vegas, and of course, the Burj Dubai, recently renamed the Burj Khalifa.

With Christopher Hawthorne of the LA Times already having written a wickedly sardonic piece on the recent opening of the 2683 foot high structure in Dubai, it is left to ponder how this new unbelievable building height, 1000 feet higher than the last record holder, compares with the depth of the longest drill mankind has created to get the oil that has paid for it. The Burj Khalifa is the yin to the yang of the ‘Bilbao Effect’, i.e. quantity over quality. And so with the question of quantity definitively answered (insert thunderclap here), it is to back to quality that we must look – most notably to our cultural institutions – to respond if not in perhaps such as overzealous a way as Bilbao, most certainly to demonstrate that architecture can still walk soft and carry a big stick.

The AGO is hence the biggest expectation of them all, a flagship for the industry of cultural upgrades that we’ve seen in cities across the nation, sometimes part of our federal government’s infrastructure support, but more often not. Edmonton is also poised to reopen its new art gallery, upgrading its old seventies Brutalist structure (not unlike the recent facelift given to our Brutalist CBC building here in Vancouver). The shortlist for the Art Gallery of Alberta was nothing less than astonishing, including Pritzker winner Zaha Hadid, as well as Will Alsop and the late Arthur Erickson. With the final commission awarded to Randall Stout, the new AGA appears as little Bilbao on the prairie, and its highly gestural form may be a big question mark for this conservative government city of mostly modernist building stock.

It is precisely that Mr. Gehry chooses not to do the obvious in Toronto that I believe is most admirable here, instead opting to walk soft and carry the aforementioned stick (a lesson that perhaps Mr. Libeskind would have done well to have learned). As we’ve all by now heard the story of how Mr. Gehry’s grandparents lived up the street, his Bilbao-less addition is solemnly respectful – less as it turns out is more on Dundas Street. As those who had visited the AGO before its Gehry renovation will recall, its most recent retrofit by Barton Myers had taken the centrality of the plan away, something which Mr. Gehry has restored, adding a swooping stair ramp in the newly recovered Walker Court – like a curious and curly exclamation point. Most importantly, the gallery’s extensive Group of Seven collection has been placed centre stage on the second floor, the crown jewel of the gallery’s holdings, nestled between the Walker Court and the new Galleria Italia, itself a beautiful Douglas fir structure over the gallery entry, with views of the adjacent inner city neighbourhood to the north.

It is a new view to the south, however, which offers a spectacular vantage point from the gallery, and is one of the AGO’s new hidden delights. Now up above the trees of Grange Park, as well as Alsop’s table-top OCAD to the east, Gehry has unveiled a new view out of the south of the building looking to Toronto’s central business district, with Lake Ontario in the background, its mid-ground composed of the CN Tower standing between the financial towers to the east and a new collection of residential towers sprouting up to the west. But it is as much where the view is from that makes it a delight, offered up as it is through a glass and aluminum-clad, volute-shaped stair sticking out of a new blue titanium clad, five-storey tower. These two spiraling stairways on the floor plate’s north and south sides are beautiful works of art in themselves, though their execution is not without flaws. Similar to the stair in Mr. Gehry’s Vitra Design Museum in Germany – a stair which the architect admitted in Sketches of Gehry (2005) he was never satisfied with – this challenging form appears in numerous iterations at the new AGO, and appears unfortunately to have been as problematic to build now as it must’ve been then.

As it happened, my visit to the AGO was concurrent with the running of King Tut: The Golden King and the Great Pharoahs, a show which in my opinion would’ve made more sense to have had at the ROM. As it turns out, the playful wheelchair ramp Mr. Gehry put in the lobby of the AGO’s new entry does not lend itself well to line-ups, and so the 250+ people waiting to get into the exhibition space on the third floor of the gallery were left to queue all around the Walker Court and back into the lobby. The result made it very difficult to gauge the contemplative aspect of the gallery, as it was temporarily transformed into a Disneyesque experience. Fortunately, the new fourth and fifth floor galleries were far removed from this calamity, and their modern art content, including the likes of Warhol, Rauschenberg, alongside Vancouverite Jeff Wall among others, were reminiscent of other great modern galleries like the MoMA and Tate Modern in their layout and finishes.

Along with the aforementioned entry lobby, otherwise known as the Maxine Granovsky & Ira Gluskin Hall, the new Dundas Street elevation of the AGO includes a now larger restaurant called ‘Frank’s’ and a much expanded gift shop. As it turns out, a small section of the gift shop is devoted to the architecture of the building, including the architect himself. Neck-ties and wrist watches available in the building’s material palette of titanium blue and Douglas fir brown are available along with small iterations of the architect’s patented corrugated cardboard creations. As for myself, I purchased a new publication on the gallery and its renovation, entitled Frank Gehry in Toronto (2009) – the product of the AGO and London based Merrell Publishing. Featuring essays by local art critic Robert Fulford, architecture professor Larry Wayne Richards, as well as the CEO of the gallery, the book’s editors cleverly chose Edward Burtynsky and his critical eye to depict the construction of the building for the book’s photography.

But beyond the discerning architect’s eye, my impression of the gallery as a user was satsified in regards to the circulation through the new and old gallery spaces, including a new section designed by Tornto-based Shim Sutcliffe Architects. I was however disappointed that some work from the old gallery had not made a reappearance in the new one. One is also no longer able to photograph any of the art, where once upon a time the gallery allowed selective photography. Back before the advent of digital cameras, I used my SLR to take photos there of a small Bougereau that is still on display, while a Waterhouse and a Monet now seem to be absent. It is surprising in this day and age, with the ubiquitous digital camera always at the ready, that there are still concerns with copyright in art galleries. Even some of the greatest galleries in the world have eased up, at least with non-flash photography, as it is permitted in the Louvre, Musee d’Orsay, and MoMA, to name only three of the world’s great storehouses of art.

Now turning some 2800 kilometers to the northwest of Toronto and the AGO, Randall Stout’s provocative AGA expansion is the final puzzle piece of Edmonton’s Churchill Square, which has more recently included the construction of a new concert hall for the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra and a library addition, along with a new amphitheatre for the square itself. With its own architectural legacy of great civic buildings – the HUB Mall at the University being but one of several exceptional examples – the city has always maintained a more no-nonsense approach to building with Canada’s winter elements. With the three glass pyramids that make up the Muttart Conservatory next to the North Saskatchewan River being a part of this legacy, it is not surprising to find the Edmonton City Hall under two glass pyramids also.

And while the form of the AGA is quite bold, the city has its share of spirited modernism, such as Peter Hemingway’s Coronation Pool and Douglas Cardinal’s Edmonton Space Science Centre. The process for selecting the architect began in 2004, when the AGA approached some 40 different architects which they whittled down to four by competition. I was at a lecture Will Alsop was giving at Robson Square shortly after he found out he had lost the design to Mr. Stout, and he could not hide his disappointment. As well, I’m certain either Arthur Erickson’s or Zaha Hadid’s scheme would have most certainly offered its own unique interpretation of Churchill Square.

The new gallery is stylistically as far removed from the existing building, a 1969 Brutalist structure, as that building was from the neoclassical library building that first housed the city’s art collection in 1940. These three incarnations of the ‘gallery in the city’ have stood as architectural signposts for Edmonton, and the new gallery, due to be open at the end of this month, will surely not disappoint. For a city that has for obvious reasons always celebrated new indoor civic space, the new lobby of the AGA is sure to be a sight to behold, if not a cup running over. With much negative publicity recently having been bestowed on architecture that has sacrificed function for form, one hopes that the curving glazing has been designed to withstand the city’s brutally frigid winter temperatures.

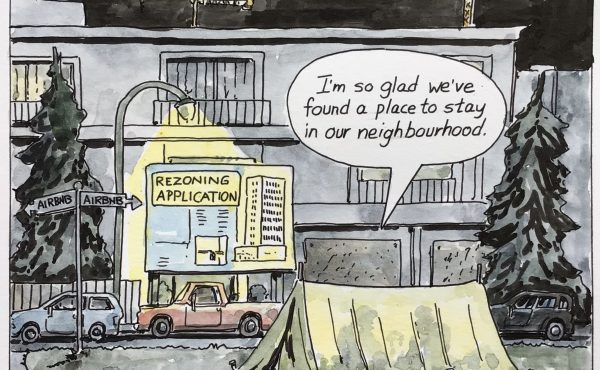

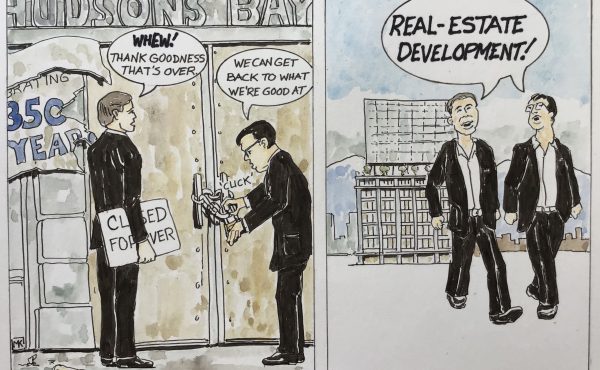

And finally, here in the Lower Mainland we have heard about the wishes of our own Vancouver Art Gallery to relocate to a larger, more up-to-date gallery. About two years ago, Richard Henriquez gave a public presentation at Robson Square of his scheme for locating a new VAG on the shores of northeast False Creek. Unfortunately, due to the site’s high water table it would seem that Mr. Henriquez’s plan will have to be abandoned, to instead be located on the old Beatty Drill Hall marching grounds (currently a parking lot). This ‘cultural compund’ on the southeast slopes of our CBD could certainly use a kick start, something which precisely a new gallery could trigger. The library square is already there, along with the Queen Elizabeth Theatre, and most importantly, there’s a newly arrived populous – numbering in the thousands – living in the towers at the downtown’s periphery. With the provincial government already having pledged ten million dollars (a modest beginning to say the least), one can only hope a new gallery will be the first order of business when the Olympics have packed up and left town in a few months time.

Many questions about the relationship between an art gallery and its host city remain unanswered – we would do well to ask our ourselves how important such an institution is to our own city? Is a great city synonymous with having a great art gallery, or is this simply an expectation we have now post-Bilbao? It is clear that Toronto and Edmonton see their respective galleries as opportunities to bring culture to the masses, allowing for discussions of aesthetics and opportunities for artists to show their work in new venues. For here is the essence of the city, the spirit and key ingredient that can keep it vital and vibrant – we must prevent the usurption of experiencing art in the world as society seems to be devolving backwards with its fixation on the two-dimensional image. It will now remain to be seen if all this talk about the VAG has at the end of the day just been posturing, or if a new bold statement of contemporary culture may be made manifest as a new art gallery for our city.

by Sean Ruthen

***

Sean Ruthen is an architect living, working, and writing in Vancouver. In February, he will be a volunteer for the 2010 Winter Olympic Games.