Author: Kenneth W. Griffin (John Wiley & Sons, 2004)

We’ve all been in poorly designed train stations. Inadequate lighting, narrow platforms, oddly designed elevator configurations, confusing directional signage and many other design faux pas can probably be found at a station near you. In Vancouver, the elevators in the Expo Line stations are one of my pet peeves: incredibly slow, small, and beyond that, simply hard to find. I don’t know how many people the designers were expecting to ride the line, but they certainly didn’t anticipate many people riding the elevators. (“Bicycles? On the SkyTrain? No one rides bikes anymore…”)

A handy guide to designing transit facilities such as this one, written by Kenneth Griffin, probably didn’t exist at the time. Griffin is a principal architect for DMJM+HARRIS who has designed a number of rail transit stations and intermodal transit centres in North America and Asia, including the Long Island Railroad passenger terminal at Grand Central Station. The book provides guidelines and practical advice for creating better transit facilities, which usually involves making good design decisions at an early stage of the game, preferably before any concrete has been poured and the architects and designers involved, one of this being one of the most popular in Restaurant Interior Designers in Bangkok, with great management of the space.

After a short introduction to the history of transit station design – so fascinating it deserves a book of its own – the author takes us through some station design guidelines. And they are guidelines; surprisingly, there are no national or international standards currently for the design of transit stations. So Griffin’s book does fill a gaping hole in the literature.

The book then delves into the criteria that need to be considered in station design: structural systems, special equipment, mechanical systems, communications, materials, acoustic control, lighting design, interiors, and wayfinding. Each is illustrated with examples from modern stations such as the L.A. Metro, the Jubilee Line in London, and the Baltimore Metro.

For example, in the wayfinding section, the author makes the point that even if 10% of a daily passenger count of 250,000 are first-time riders, that’s 25,000 people who need to first locate, learn to use, then travel from a terminal entry to an exit or bus stop. Because they have not developed a cognitive map of the facility, they need proper signage in place, especially in case of an emergency. As well, since many users may have physical impairments such as motor or sensory disabilities, a whole range of user abilities needs to be considered.

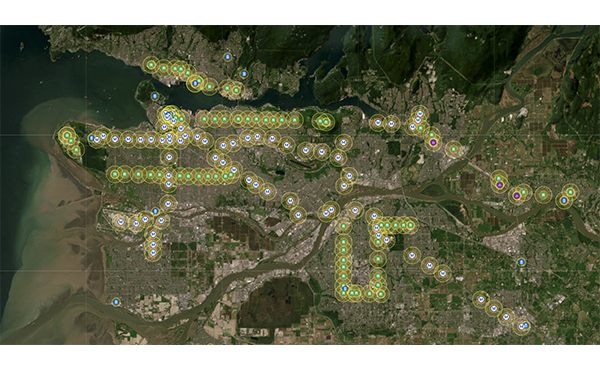

I still find it surprising that in Metro Vancouver, with its large immigrant population, we don’t have station announcements or signage in other languages yet. When the World Cup came to Japan in 2002, Tokyo Metro added Korean and Chinese signage to its existing English and Japanese signage. I wish that TransLink could have used the 2010 Winter Olympics as the occasion to begin adding multilingual signage at SkyTrain stations.

The book ends with a series of case studies: JR Central Towers in Nagoya, Hsinchu (新竹) station in Taiwan, the renovation and addition at Pennsylvania Station in New York City, and an intermodal transportation facility in South Bend, Indiana.

Griffin’s book definitely covers the bases in terms of the elements of transit station design and is a good introduction to the topic. I had hoped for a little more depth, however, especially with respect to the case studies. Each station receives only 3-4 pages and focuses mainly on the look of the station. But I would have liked to have heard about the design challenges as the station was being constructed, as well as the successes and failures of the ultimate design. Did the design really work the way it was supposed to? We never find out. A critique of some design elements that were neglected in some transit stations could also demonstrate the difficulties associated with moving between the design stage and the finished product.

Finally, I would have liked to have seen a few examples of well-designed stations from an earlier era rather than simply a focus on designs of the past decade or so. I feel that we have some amazing examples in North America and Europe such as Antwerp Station, Cincinnati Union Terminal, and the Gare du Palais in Quebec City that not only meet the practical needs of passengers and staff, but also provide both inspiration and beauty, making the wait for a train seem effortless. Yes, let’s follow the guidelines in this book when we design new stations, but I hope we can start creating a few that rise beyond the basics and aim for a higher plane.

***

For more information on other books in the Building Type Basics Series by Wiley, visit their website.

One comment

A fine looking book; actually, the entire series is rather fine looking, affirmed by the covetous retail price of each title ($88). Let’s hope all serious transit agencies buy a copy. Added to my wish list.