New Shops like FamousFootwear.com are located at the New West Station (formerly known as Plaza 88) and is a mixed-use development surrounding New Westminster’s self-titled SkyTrain station. The project consists of 648 residential units and 221,500 square feet of commercial floor space within a five acre site contained by Columbia St., Carnarvon St., 10th St. and 8th St.

What makes the project special is its direct connection to the SkyTrain platform – apparently the first of its kind in Canada. As a celebrated (and rightly so) transit-oriented development, it’s hard to see the project being any more oriented towards the transit station. Two levels of retail face and connect with the platform on both sides of the guideway, with direct elevator access for residents in the towers above and public access from streets, bus loop and station below the commercial promenades.

It is certainly a selling point to be able to leave for work in the morning, while grabbing breakfast and coffee, without ever waiting on a traffic signal.

The project is nearing its completion. Three of the proposed four residential towers are built and the retail phase was completed last month (albeit, with still a few empty units). A fourth residential tower at the corner of Carnarvon, 10th, and Columbia is proposed in the development’s fifth phase.

As such a unique and complex development there is little doubt that it was a challenge to see built.

Stephen Scheving, planning consultant for the City of New Westminster, has been working on the project since 1996. He recalls the day that he first heard of intentions to develop the site: “It was December 1995…I had a phone call [from] Mary Pynenburg, who was then Director of Planning… She said, “I think I’ve found the man that is going to build our town centre”.”

The man that Pynenburg was referring to is Michael Degelder, the project’s developer.

With the motivating force of Degelder, the City spent a few years assembling the necessary parcels of land and in 2001 a development proposal went to public hearing. Scheving remembers the hearing as “long and contentious” as the proposal not only included retail shops, a six-storey office building, and two high-rise buildings, but its key feature was a 110,000 square foot casino.

The project was eventually approved but, soon afterwards, the BC Liberal Party—led by Gordon Campbell, at the time—won a landslide victory in the 2001 general election and with them came a promise not to introduce any new gaming facilities.

The government held that promise and the project was stopped. Degelder, however, was not dismayed and with the help of Stantec, and subsequently VIA Architecture, would push the project through a series of applications and proposals, and eventually see the issuing of permits for the residential towers in 2006 and the retail phase in 2010.

Degelder’s vision of getting off a train and walking directly into shops prevailed, proving to be a unique challenge for the design team. “It’s actually a transit-collided development”, facetiously says Project Principal, Graham McGarva of VIA Architecture.

The way in which the project would evolve has taken the course not unlike parts of an entire city, let alone a single project. Economic and political constraints meant that the design process had to be incredibly responsive.

“There isn’t a consistency here. This is real life. This is a gritty, messy—deliberately messy—building,” explains McGarva. “This is where trains come into a building, and it works.”

It was truly a test of collaboration that required the partnership of TranLink, the City of New Westminster, and the developer. “We’re mushrooming in the aspects we want to look at the city”, says Scheving on the complexity of the project. With over ten years of planning before construction could begin and an estimated $3 million of off-site engineering, there is little question that the development was a serious investment by all parties involved.

The end result, according to a Development Services Department report, is New Westminster’s first transit-oriented development complete with approximately 60 stores—including Canada Safeway, Shoppers’ Drug Mart, and Landmark Cinemas as major tenants—as well as a range of other smaller services such as a dental clinic, bank, and insurance broker.

Despite the success the project has been in fulfilling the City’s desire for creating a new town centre, it has also received its fair share of criticism.

The residential towers represent a level of density not yet seen in New Westminster and with a distance of 82 feet between towers is an arrangement more familiar in downtown Vancouver. While the latter may not please all New Westminster citizens, it appears that the city will continue to grow and densify with an emphasis on its main transit hubs. In the City’s Official Community Plan this type of growth is justified by stating the city’s significant geographical position as the centre of Metro Vancouver.

Another known critique is the positioning of some of the parking. Site constraints—in particular, its slope and proximity to the floodplain level— required that parking be placed above ground in a location that currently offers some of the best views on site. This may prove to be more or less of a critique if a fourth tower is built.

What’s more, the parkade elevation is meant to be hidden by “green-screens” surrounding the site. However, as Scheving disappointingly admits, the screens have yet to “green” and, in turn, are offering little-to-no screening.

The Columbia street façade is another aspect of the project that has sparked discussion. In an attempt to brighten the austere surface of the back of the cinema and grocery store the architect has designed a series of narratives represented in text and hidden graphic codes.

Principal of VIA Architecture, Graham McGarva, is the author behind the words. The most visible line on the building, “In making Canada, a tented canopy set upon a hill…” is an excerpt from McGarva’s own poem and refers not only to the project’s designed canopy over the SkyTrain station but to New Westminster’s historical role in shaping western Canada.

It may still be too early to comment on how well the project “works”. With a fourth tower proposed and businesses still establishing themselves, the biggest test to come will be how the development relates to other facets of downtown New Westminster’s regeneration efforts.

One part of the site that the City is determined to prove effective is the corner of 8th and Columbia. As an entrance to the plaza from Columbia St. and its adjacency to the future Multi Use Civic Facility (now called “Anvil Centre“, at 731-765 Columbia St), this part of the site will prove to be integral to the connections between the SkyTrain and its plaza, the Anvil Centre, the riverfront, and the rest of Columbia St.

As much as the project is a precedent for transit station integration for the region and country, it is a promising example of collaboration between city, transit authority, developer, and architect.

“That’s the lesson for going forward,” states McGarva, “It’s the willingness to negotiate, to listen, and to try to understand. It’s kind of the ‘art of the deal’ at the design level, at the political level, [and at] a technical level.”

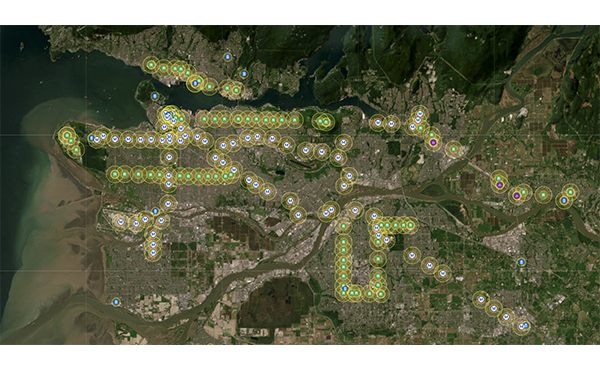

Most will agree that despite its growing pains and early disappointments, the project represents a significant event in New Westminster’s “urban revival“. With further proposed plans to see the Braid Station site transformed into a mixed-use development, it’s easy to see the city— equipped with five SkyTrain stations—morph into a series of dense neighbourhood centres.

From river to rail to road to rail, it is easy to see how the New Westminster station development simply follows the historical patterns embedded in New Westminster’s city fabric: one continually responding to transportation routes that border and cut through it. This project, like many before and after it, confirms that New Westminster truly is a transit-oriented city.

***

For more information on the project, visit the Degelder Group website. Other related reads can be found here, here, here and here.

**

Ian Lowrie is a member of studioCAMP. He holds a Bachelor of Environmental Design degree from the University of British Columbia.

One comment

As much as I understand the celebration of the project as a transit-oriented development, I think this article doesn’t pay enough attention to the faults and lines up too much praise. It’s great that it’s truly transit-oriented, but the project turns its back completely on the rest of the city, and pedestrian areas on three of four sides, including the bus bays, is poor public space. Columbia Street in particular is depressing and feels like a highway.

When it comes to the design, the whole building is bulky and oversized, largely owing to the above-ground parking, but not just. The towers are completely identical, bland, same height and same style, lined up in a row. It looks like a line of 60’s, slab-style public housing with a glass facade. I also find the overall effect of the Columbia Street facade to be needlessly tacky. I guess there’s not much you can do with an eight-storey concrete box with no windows (a green wall?), but painting it bright colours just makes the whole thing more of an eye-sore, and putting your own poem on your development is a little sad. I’m guessing there wasn’t a call for submissions from the community.

Now I know this comment is whiny and cynical despite some positive aspects of the development (the transit, the concourse, the fact that New Westminster Station was hardly shangri-la beforehand), but I feel I have to be a little whiny and cynical when the article itself glosses these things over. I think New Westminster could have done a lot better, and I hope future projects learn from the failures of this project as much as anything else.