[This six-part series was written in 2007 and is set in 2030. It describes one scenario of how Vancouver became a One Planet City—a city that uses only its fair share of Earth’s resources. If you missed the earlier pieces, be sure to read Part 1 and Part 2]

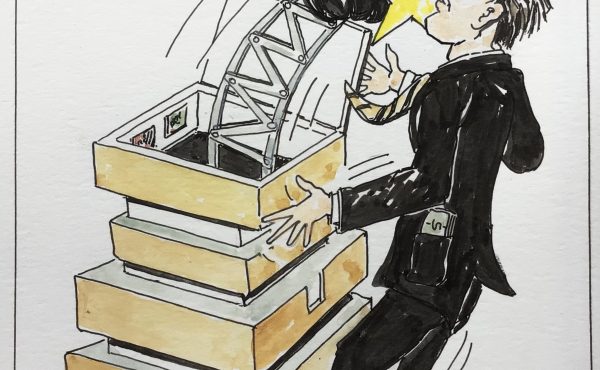

By 2014, complete neighbourhoods were developing due to Micro-centres, Radically Mixed-used Areas and Micro-amenities—and this made a great business case for a custom furniture maker to relocate to Vancouver. At first, the furniture shop had to install a much higher level of noise and dust mitigation to meet the performance zoning, but they were closer to their customers in one of Vancouver’s upscale neighbourhoods and the craftspeople lived within walking distance of their work.

As is often the case, a web of serendipitous meetings and relationships between the shop owner and an influential municipal decision-maker facilitated using shop waste as fuel—gasifying it in a Combined Heat and Power unit and feeding electricity back into the Grid while sending heat to the new neighbourhood energy utility. In return, the shop owner brokered a deal with City to access beautiful hardwoods—a deal that required only a slight re-visioning of their existing fruit tree policies. Coincidentally, the City was developing a city-wide urban agriculture plan and, from this humble beginning, the City of Vancouver’s Urban Forestry Program was born. Started in 2015, it is now reaching prime wood production.

Productive urban forests

A key insight helped develop Urban Forestry: a lot of the hardwood used by local artisans could come from fruit trees, which the City planted intensively on streets and in parks. With both fruit and wood going to good use, the focus moved to planting strategically, with each neighbourhood receiving a different variety of fruit. This helped create harvest festivals which move throughout the city with the seasons—in October the smell is so enticing, you would swear Kitsilano is built of apple pie. The best fruit is sold through the Farmer’s Outlet network. Most centres have a Farmer’s Outlet, which sells the produce of hundreds of local urban and rural farmers and credits the farmer’s account. The farmer saves time on retailing and is able to spend more energy doing what they do best. The majority of the fruit is juiced or processed, and sold under the Vancouver brand name, by Van Food Processors, a thriving company that was started by disgruntled planners after the Great Strike of 2007.

Street parks

Fruit trees are not the only change on our streets. As it became clear that buying large pieces of land for parks would be difficult or impossible, city staff developed a new strategy. They transformed many of our secondary streets from straight ribbons of asphalt and concrete to slightly winding linear parks. Some even have long jungle gyms that draw children through play structures as their parents walk along the sidewalk.

Garden plots, not parking spots

In many of the medium-density areas the change to street parks began with a bylaw that required any resident with an underground parking spot to use it. The space freed up by removing parked cars has been put to many creative uses. The first streets to do this in 2008 were essential to the City meeting its ‘2010 garden plots by 2010’ target as the parking lanes were converted to gardens, leaving two lanes open for accessibility and deliveries.

Since the successful conversion of those first streets, neighbourhoods have created endless variations. One very successfully combines a small visitor parking area at the head of the block, a large mid-block garden and a recreational area at the end of the block. A single lane for vehicles is more than adequate for the load that residential streets need to carry, and occasional pull-outs accommodate the HandyDart and delivery vehicles.

Sport and recreation

Some of the recreational areas became neighbourhood hotspots for half-court basketball, and the sport’s popularity surged as the Outdoor Recreation programs shifted focus off of League competition, with their costly status symbols of uniforms and sponsors and expensive shoes. The old leagues forced people to travel all over the city whereas the new focus is on neighbourhood pick-up games. The popularity and skill demonstrated has resulted in an annual televised tournament of pick-up basketball. Of course, in addition to the many other benefits, this program is much more cost-effective than trying to buy, build and maintain expensive fields and gymnasiums.

The activity on the street makes people feel safer, the Vancouver Happiness Index has risen as neighbours make connections with each other, and the just-out-the-front-door accessibility has greatly increased Vancouverites’ average fitness level.

Green streets

Another change in the streetscape began when the City realized that the Napoleonic march of strictly spaced street trees, all of a single variety, was not doing very much for habitat, biodiversity, or a sense of connection to the natural world. They began planting clumps of trees, berry bushes and ground cover, highlighting the new, winding streets.

Where street parking is required on secondary streets, Grasspave is used, which allows grass to grow while preventing damage caused by vehicle tires. This system also allows soil microbes to break down leaked oil and antifreeze before it reaches the storm sewers and the ocean. To bring the cost of green streets down, the City’s Design Department is developing a locally manufactured substitute for Grasspave, using plastics collected in the Blue Box.

Food Security

Although the fruit trees shading our streets are perhaps the most visible part of Vancouver’s Urban Agriculture strategy, they don’t tell the whole story. In fact, the majority of our salad vegetables and herbs come from back yards, some front yards, and reclaimed streets around the city. The food security that comes with local agriculture has been a lifesaver over the past decades as fuel prices quadrupled the cost of shipping, and storms and droughts punished the irrigation-dependent monoculture fields of California and Mexico.

Our rare degree of food security has greatly increased the Vancouver’s relative affordability, as other cities compete in agricultural auctions for enough food to feed their residents. The big shift came when food production became the first consideration when selecting plants on city-owned land. Security fences became blackberry bushes, decorative hedges became lush plantings of green tea, herbs flourish in nooks and crannies everywhere, and grape vines twine up trellises to shade the south face of buildings from the summer sun and fill the air with the thick, sweet smell of ripening fruit.

The ALR and sea level rise

Another major element of our food security involved shifting some of the investments of the Property Endowment Fund to agricultural land in the Fraser Valley and the Interior. The City was foresightful enough to avoid investments in huge areas of the former ALR in Richmond and Delta, which, despite global rallying to cut GHG emissions, were inundated in the 2016 Flood when great chunks of Antarctica’s Western Ice Sheet broke up and slid into the ocean, raising sea levels by 94 cm overnight. Looking back, it is amazing how little planning was done to anticipate the possibility of sea level rise. The Dutch started paying attention in 2005, which should have been a pretty big red flag. We also could have paid more attention to several cities in India; they were years ahead of us on infrastructure planning for climate change.

Urban farming

Many Vancouverites enjoy gardening of some kind, though for most it is a tub of cherry tomatoes, a little fresh basil on the balcony or a small rooftop garden. This allows urban farmers, who rent or sharecrop yards from homeowners, to grow 40% of Vancouver’s vegetables. Often just a few blocks from a Farmer’s Outlet, Vancouver’s version of Small Plot Intensive farming (SPIN) have delivered one of the City’s biggest reductions in Greenhouse Gases. Not only can the produce be moved by human power, but the permaculture-influenced farming methods eliminate the need for chemical inputs.

Chickens (without the noisy roosters) are found on every block, also supplying the Farmer’s Outlets, as do the honeybees, which are so critical for pollinating food crops. Just as the fruit trees have helped create unique neighbourhood character, various areas have become famous within the city for the flavour of their honey, the sweetness of their tomatoes, or their delicious grapes. The increase in agriculture also saw increases in our Happiness Index, as more people work outside, talk over back fences and meet their farmers at the Outlets.

Join me next time when we look at transportation, building efficiency and Starlight Neighbourhoods.

***

He has consulted for the City of Vancouver. BC Housing, Industry Canada and private sector clients, and taught Sustainable Design. While researching behaviour, one of his pilot projects increased recycling and composting by 250%.

He has blogged for TreeHugger.com and theTyee.ca. His recent writing and presentations can be found at www.SmallAndDeliciousLife.com