[This six-part series was written in 2007 and is set in 2030. It describes a scenario of how Vancouver became a One Planet City—a city that uses only its fair share of Earth’s resources. Read the introduction here.]

Life in One Planet Vancouver is much like life in Four Planet Vancouver; once the change was made, it has become hard to imagine any other way of life. It is interesting, though, to look back at where we started many years ago. So, before we get to the stories of wildflowers and children playing, let’s look at the changes that brought us to where we are in 2030.

To begin with, we accepted that we can only do what we can do, but we can almost always do more than we think.

Many people said that our efforts would be negated by outside pressures and the actions of the rest of the world. In fact, we found that many other cities and states were often waiting for someone else to take the lead. Once the ground was broken on new initiatives, they were often happy to learn from and refine these practices for their own use. By ignoring the naysayers and striving to be a global leader, our city truly changed history.

The most important change that allowed us to succeed and emerge as leaders was adopting social marketing and social research as a key component in program and policy implementation. Study after study showed that people, even with education and a financial incentive, often did not do the right thing. For example, back when every house had a giant tank to heat water, disappointingly few people installed water heater insulation blankets, despite widespread availability and nearly immediate cost savings. Social marketing and research practices have provided the scientific rigour that ensured the success of the programs that have made Vancouver what it is today.

Aligning our budgetary structure was also critical to our success. We taxed ‘bads’ and rewarded ‘goods.’ Internally, we eliminated the end-of-year spending frenzy caused by use-it-or-lose-it budgets. Another big shift involved a move to tax land instead of improvements. After all, we want improvements! Tax shifting has shown up in so many ways—from road use to solid waste management—that it is hard to imagine how we functioned without it.

Finally, we embraced experimentation. Rather than conducting exhaustive studies, focus groups and consultations to find the single ’Right Solution’ that was inevitably outdated before it was finished, we came to understand the strength of diverse solutions. We were not afraid to try, fail and learn, because we finally acknowledged that our success depended on flexibility, innovation and courage.

So, what does One Planet Vancouver look like?

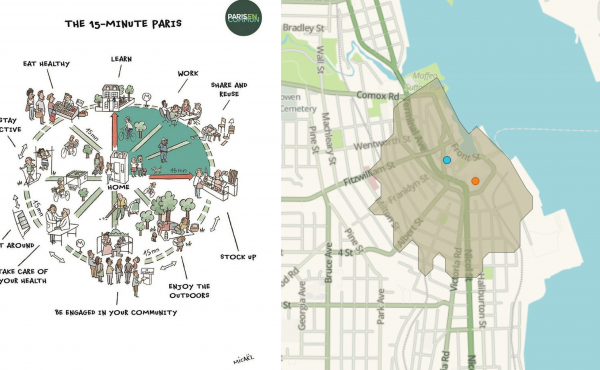

Three key elements are present—micro-centres, radically mixed-use areas, and mixed amenities. Let’s take a closer look at each:

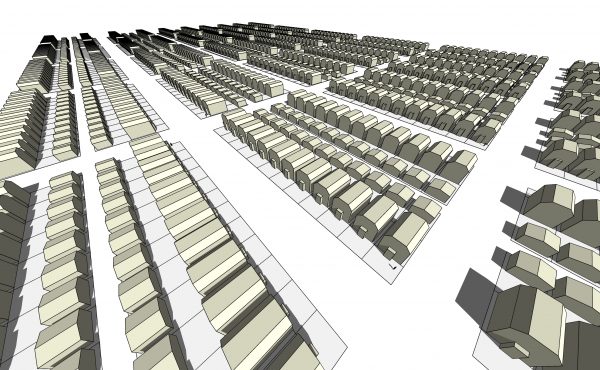

Micro-centres

The City of Neighbourhoods has become the City of Many Neighbourhoods, each anchored by a small business centre. A poorly named initiative from 2013 called ‘Five in Five,’ sought to put five services—a corner grocery and Farmer’s Outlet, a restaurant/pub, a drugstore/postal outlet/digital output shop, and a library kiosk and coffee shop/deli—within five minutes walk nearly anywhere in the city. Each centre provides employment within the neighbourhood alongside support services for the many businesses that have been integrated into the residential areas.

Radically mixed-use areas

In fact, purely residential zoning has almost ceased to exist. All of the low-rises built since 2009 have provided commercial spaces on the ground floor. An amazing diversity of businesses have filled them—from the architects who live upstairs, to start-up design and fashion houses that are happy to be out of the city core in exchange for lower-cost space. Even light industry has moved into residential neighbourhoods, drawn by performance zoning and quality of life for their employees.

Many of these businesses have moved from suburban business parks. The unpredictable costs of transportation fuel made it difficult to retain staff, and the integrated neighbourhood energy utilities that Vancouver offered were very attractive to manufacturing. The integration of land uses delivered one of our biggest reductions in Greenhouse Gases, slashing almost 10% of our emissions.

‘Five in Five’ also helped us solve a puzzling problem—as we densified single-family neighbourhoods, no one could figure out how to capture the value of development from small infill and other intensification projects. There simply was not enough money from infill projects to build the large-scale amenities like libraries and community centres that residents wanted.

Micro-amenities

The first step towards a solution started years ago with a library kiosk. A small developer wanted to knock down three houses and develop 15 units on a single site. Development in the area was not at a rate that would allow the city to amass Development Cost Levies, nor was there a nearby site on which to build large, traditional amenities even if the money could be found.

A creative solution emerged when the developer agreed to provide public space on private property within the development; in this case, to provide an sheltered area with a separate electrical meter, for the installation of a new kind of amenity, an unstaffed library kiosk.

Now, library members simply request their books be delivered to their local BookBox. The Bookmobile puts each members’ new books in a separate box—like a large mailbox—and picks up old books to return to the Central Library. After being notified their book has been delivered to the kiosk, the member simply swipes their library card through a reader, the appropriate door opens, and they take their book.

A similar service came out of the next development when the developer was required to provide space for a community room. The NeighbourSpace provided much of the service of a community centre, but is was only a single room—again unstaffed. Outfitted with hardwood floors, a washroom and good lighting, the community room satisfied a surprisingly large number of the neighbourhoods’ need for space. Yoga, martial arts and dance classes took place there, as well as movie screenings, childcare activities and book club meetings. Access was given to instructors via a card reader, though anyone could sign the room out and pick up an access card from the BookBox. A security company monitored the room when it is not in use and cleaners took care of its upkeep.

The original NeighbourSpace and BookBox are still going strong now in 2030, decades after their original creation. They have since diversified and evolved into a number of ways, adding an important fine-grained vibrancy to the city. Ultimately, this approach—trying to satisfy the need without feeling bound to ‘do it the way we have always done it’—has made for much more exciting neighbourhoods.

Join me next time when we look at urban forestry, fruit festivals, and green streets.

***

He has consulted for the City of Vancouver. BC Housing, Industry Canada and private sector clients, and taught Sustainable Design. While researching behaviour, one of his pilot projects increased recycling and composting by 250%.

He has blogged for TreeHugger.com and theTyee.ca. His recent writing and presentations can be found at www.SmallAndDeliciousLife.com

One comment

This is a pretty great read. Thanks for reposting!