Authors: Roy Tomalty and Alan Mallach (Island Press, 2015)

Urban America has a thing or two to learn from north of the border—that is what Ray Tomalty and Alan Mallach argue in their new book America’s Urban Future: Lessons From North of the Border. Why? Because Canadian cities are more sustainable and livable than American ones.

In terms of livability, people who live in Canadian cities have a higher quality of life and are physically healthier than those in American cities. There is also less residential segregation (between whites and non-whites) and less social inequality in Canadian cities. As for environmental sustainability, Canadian cities use less electricity and water, and produce less greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants. Some of this may be attributed to more people in Canada walking, cycling and taking transit to work, and less of them owning cars; Canadians, per capita, commute about half the distance to work Americans do and consume about half as much gasoline. As a result, Canadian cities are ranked less vulnerable, i.e., more resilient. (It should be noted that the above are trends based on a number of studies, each of which surveyed different groups of cities from both countries. There are certainly some US cities which do well and better than some Canadian cities—in measures of both environmental sustainability and livability.)

These differences have much to do with urban form. Tomalty and Mallach write, “Canadian cities are more compact; have a greater mix of daily destinations within walking distance; and have more stable and healthier central cities, better transit systems, fewer highways, fewer roads, and more sophisticated cycling infrastructure than US cities,” which, by contrast, are more spread out and car-dependent.

The authors cite a number of reasons for this. The horizontal, suburban growth of US cities is subsidized directly by policy like the federal deduction on home-mortgage interest payments; and indirectly by low fuel taxes, an extensive highway system, and free parking. And while US cities are incentivized to sprawl, urban growth in Canadian cities is often contained by regional plans and policies.

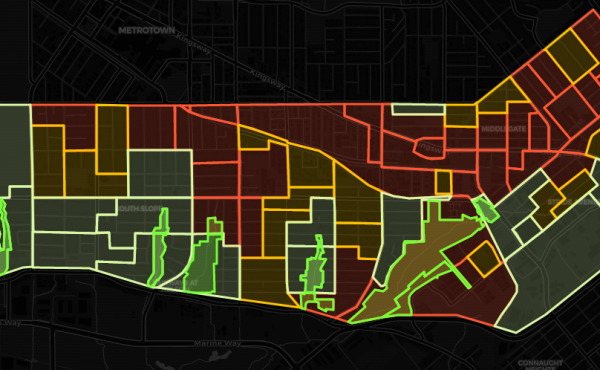

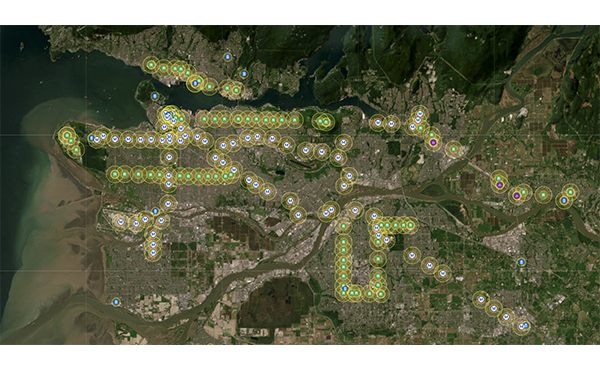

Canadian cities are creatures of their provinces, which can amalgamate cities and create regional authorities. The result, generally, is coordinated planning among a region’s cities to manage growth and protect the environment and agriculturally productive areas. The authors write, “Greater Vancouver is probably the best-known example along these lines, having benefitted from several decades of a consistent regional planning vision as expressed in its growth management plans, starting in 1975 and reiterated in 1996 and 2011.” (Tomalty and Mallach are referring to the region’s Livable Region 1976/1986 report (1975), Livable Region Strategic Plan (1996), and Regional Growth Strategy (2011).) US cities, meanwhile, are rarely under the purview of regional or state policies and plans—often with the result of competition among one another for investment in growth and development, unchecked sprawl, and lack of a regional vision.

In America’s Urban Future, Tomalty and Mallach make a well articulated case that if US cities want to get serious about livability and environmental sustainability, they have a lot to learn from Canadian ones. Among their recommendations are: integrating local planning into regional systems, increasing mixed-use and mixed-income development, and reducing incentives for sprawl/auto-dependent development. Moreover, they note that Baby Boomers and Gen Yers want this. Research shows both groups are seeking to live in walkable, transit-friendly neighbourhoods.

This is not to say Canadian cities don’t have work to do. For example, the authors note that, even though it’s still higher than the US’, Canada’s active transportation mode share (the proportion of walk, bike, and transit trips) has declined since the mid-1970s. And even though Canadian cities have benefitted from good regional planning, it appears it can’t be taken for granted, even when progressive policy is in place.

In a recent article in Business in Vancouver, Peter Ladner writes that Greater Vancouver’s provincially approved regional plan “calls for ‘compact, vibrant communities connected by an efficient transit network, an effective goods movement system and affordable infrastructure.’” Its underlying goals are “clean air, economic health, protection of farmland and green space, affordability, shorter commutes, healthy active lifestyles, reduced greenhouse gas emissions and more.”

The BC Government, meanwhile, is planning for the construction of massive car-oriented infrastructure—in the form of a new 10-lane bridge and interchange system connecting Richmond and Delta. I would contend that the new bridge and interchange will make it easier to drive (especially longer distances), encourage urban/suburban development on agricultural land, and facilitate sprawl. Ladner writes, “Projects like Tsawwassen Mills and the new 10-lane bridge are cementing Metro Vancouver into a heavily subsidized SOV-dependent future, in spite of overwhelming evidence that this will come at a huge cost to the social, economic and ecological health of the region.” Based on their research, I’m sure Tomalty and Mallach would agree.

Canadians or Americans alike should read America’s Urban Future, especially if you care about urban sustainability and livability, could use a primer on current research into how both are measured, or just want to help make your city or region a better place.

***

For more information on America’s Urban Future, visit the Island Press website.

**

William Dunn lives and works in Vancouver.