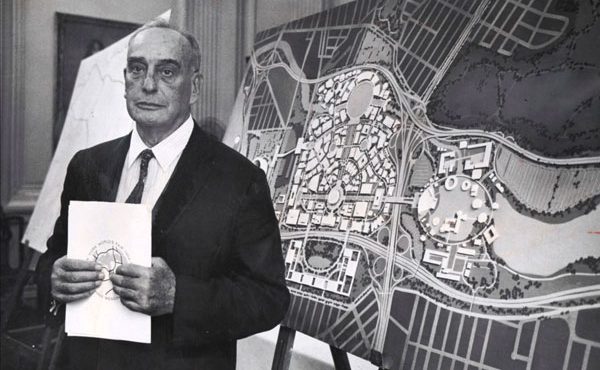

The recent publication of former Vancouver head planner Larry Beasley’s new book Vancouverism provides an opportunity for us to both look back at how this housing affordability mess all began and look forward at how we might extract ourselves.

His book is aptly titled for this purpose: Vancouverism. What does this even mean? Ending in –ism, one expects a political grounding. But Vancouverism is no ideology, as the author forcefully exclaimed at his first formal book launch in Vancouver last week.

This lack of political intention leaves one feeling sad and angry, an anger apparently shared by most Vancouverites these days. Not an anger aimed at Beasley or his planning colleagues, but instead focused on how an idea that seemed so harmless — urban design “niceness” just for the sake of being nice — could be the vehicle for handing over the city to the ravages of unbridled global capital.

Beasley made it plain in his remarks, and in answers to subsequent questions from the floor, that he wished he could have anticipated this result and helped include policy mechanisms to provide not just a livable and gorgeous city, but one that would provide affordable homes for the middle class — a class currently shut out of the beautiful urban areas he helped build.

What he and many others failed to anticipate was that Vancouverism would end up turning its back, unintentionally, on the social purpose of the city — failing to provide, in his words, good places to live for “our people.”

In my view, and I think in his, our collective failure boiled down to a missed chance to cement the word social, or social-ism, into the Vancouver-ism concept.

Maybe the word we needed was Vancouvial-ism.

The good ol’ Yaletown days

Don’t get me wrong. No blame, no foul on Beasley. For decades, Vancouverism spawned an urban design cottage industry for folks who believed in Vancouverism and were spirited here and there around the globe to talk about it. I was one of them. It was great! Vancouverism!

All you had to do to lure the middle class back downtown was to provide the very things that made the suburbs such a roaring success: safe places for kids, great parks, good schools, a pool with a hot tub, and cheap eats. Yaletown had all that in spades. Plus amazing views and lawns mowed by the city.

What’s not to like?

In the early 1990s you could buy a condo in Yaletown for a reasonable price: $350 a square foot, compared to $2,000 a square foot now. Ahh, those were golden days. Of course, back then it didn’t seem anywhere near as great as it does in the rear-view mirror. Back then it was too suburban, too yuppie, too clean, with none of the “edge” of Manhattan.

What I wouldn’t give to have that world back again, a world where a room with a view was more than just a distant dream. Then it was something any middle-class kid could expect to move into within a few years — not after saving up for the 50 years that dream now requires.

As Beasley spoke, I was lofted back to those golden years on a mental magic carpet of vivid imagery. I really have to hand it to him: he painted a picture of paradise in just a few words, punctuated by a gleaming smile contrasted with suntanned skin. I was, as I listened, swept back 20 years, when Beasley spun this same vision to every man, woman and child he came in contact with, from the most modest neighbourhood resident who knew nothing of planning to the richest and toughest developer from Bosa or Concord developments. It was amazing.

The consummate listener

And unlike his successors, Beasley had one crucial talent. He was, and is, an amazing listener. It brought me back to a moment in the ’90s when his control over what would eventually become the Olympic Village project was only partial. The city’s real estate department was actually in charge, and its vision, to say the least, was blinkered. Beasley was able to maneuver into a position where he provided planning and design input with the New Sensation Homes team into the project and, to this end, organized a multiday design workshop that engaged the best designers in the city competing to complete four different plans for the site, all in five days, all in the same room.

I was fortunate to be given a role in organizing the event, so attended the initial meeting where over 20 of these big egos were assembled. We all sat in a giant circle on the top floor of the very weird Masonic hall (which overlooked the site) where the most untethered of these big egos radiated the most toxically bad vibes imaginable. Beasley opened the meeting by inviting every single person in the circle to give their own personal vision for the site, all without laying out any ground rules.

As people took turns speaking, the atmosphere gradually improved. As these feelings were shared, Beasley said nothing at all. He only actively listened. His energy was like a composer, directing the flow with nods and shifts of a shoulder and encouraging facial signals, saying nothing until the end. After everyone had their moment in the spotlight, he did the magic thing that I believe characterized his tenure. With a smile, he began with “so what I heard is…” and continued to unspool a monologue that touched down here and there on most of what was said, prompting staccato nods from individual members of the group as their thoughts were echoed.

Two-thirds of the way through his 10-minute recapitulation, it dawned on me: “This son of a gun is a public process sorcerer. He knew exactly what he was going to say when he walked in this room.” He only refashioned it using the terms and images of others, refashioning their more or less coherent visions of the future into something they all could recognize, but which was entirely his at the same time.

We all agree

Back in the present, at Beasley’s book launch, I thought how much we needed this conjurer’s skill these days, when speaking about our current urban existential crisis seems like the curse of Babel, each of us speaking different languages in separate solitudes. Our plight was made vivid when a question from the floor provoked a bit of back and forth between Beasley and journalist Frances Bula (who joined him for the Q and A by virtue of having contributed an extensive prologue to Beasley’s book).

Bula, after an admirable start trying to place our current dilemma into its global context by connecting our problems with the failures of “neoliberal capitalism,” descended from these lofty heights to the all-too-familiar rhetorical fever swamp, blaming our current problems on privileged NIMBYs, “residents for decades with a lot of time on their hands,” and proceeded to polarize the debate by praising the young YIMBYs who in her view were bringing fresh voices to the table.

Beasley listened politely, but when it was his turn to respond to the same question flashed his trademark smile and said, “I am an optimist” as a preface to explaining that he had never been in a situation where people did not eventually agree. He suggested that we all want the same things but may use different words. We want connection, we want a safe place for our kids, we want beauty, we want to feel at home, we all agree. He repeated his loosely defined phrase of “affordable homes for our people” a second time that night, and ended his answer almost apologetically repeating “but I am an optimist.”

Oh God, do we need such sorcerers now. I am reminded of lesson 17 of the ancient Tao Te Ching:

When the Master governs, the people

are hardly aware that he exists.

Next best is a leader who is loved.

Next, one who is feared.

The worst is one who is despised.

If you don’t trust the people,

you make them untrustworthy.

The Master doesn’t talk, he acts.

When his work is done,

the people say, ‘Amazing:

we did it, all by ourselves!’

That in a nutshell is Larry Beasley.

We are in a place of despair. As Bula said at the launch, in her 30 years working as a Vancouver journalist she has never seen people as angry about housing as today. We grit our teeth in a rage of scapegoating: it’s the NIMBYs, the YIMBYs, the developers, Asians, white people, old people, the privileged, West Siders, coddled millennials at fault. And we get absolutely nowhere.

Beasley was right in how he ended his talk. He hoped that by writing down this history, and in passing this ethos down to a new generation, we could use last century’s methods to collectively work our way out of this century’s problems. If Vancouverism was anything, he clearly said, it was a way of talking about the things that mattered to all people, of all ages, of all incomes, in all parts of the city. To work with, and for, “our people” — however we might define that — to bring Vancouverism to the next level.

So let’s put the Social-ism into Vancouver-ism.

Vancouvial-ism.

***

This piece was originally published in The Tyee.

**

Patrick Condon is the James Taylor chair in Landscape and Livable Environments at the University of British Columbia’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture and the founding chair of the UBC Urban Design program.

One comment

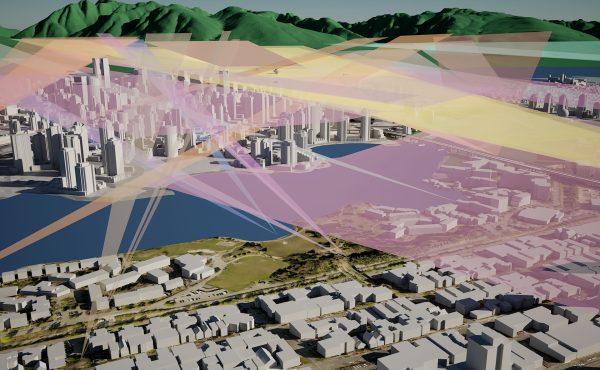

While I have had many occasions to talk with both the author and Larry Beasely, I take a much different view on the ‘Vancouverism’, which I think simply boils down to ‘towers-and-skytrain’.

In my view, the regional plans (Livable Regions Strategic Plan of 1996, and the Regional Growth Strategy of 2006), along with the ALR (Agricultural Land Reserve 1974/78), are responsible for the Housing Crisis we are suffering today with house prices 12-times over median household incomes.

Put another way… with the Canadian Dream bleeding on the floor its life about to expire.

I know Patrick Condon shares some of these concerns. I’m not so sure about Larry Beasely. Back in the day we agreed that towers should be limited to the downtown peninsula. Of course nothing of the sort was ever in the plans. The towers simply rode the rails of the Skytrain from the Expo 86 site to the major ‘town centres’ in the GVRD. Once the pump was primed, they also built in the North Vancouvers and White Rock, places where the Skytrain will never go because it is too expensive, and because it fails to meet the full spectrum of transportation demand.

Francis Bula, a resident of Mount Pleasant—one of the neighborhoods that were up-zoned in a very shaky process by the now defeated politics of Vision Vancouver—brought the academic and the city planner back in line with reality by pointing to the obvious: The level of rancour among the people—like the land valuations—has hit an all time high.

Thus, it is disappointing to read a review praising a planning ideology that ought to be stripped naked for what it really was—a cash grab using the Hong Kong model to sell our land the off-shore (Chinese) capital. Take that away, and the Vancouverism implodes.

Lost in the words of the reviewer, and the writer as well, is any sense of appreciation for what must ultimately replace the Freak Vancouverism—a west coast vernacular built from the traditions and materials of this place, nestled in the pristine landscapes and ecosystems that make ours such a unique geography on the planet, priced within the reach of every Canadian and designed to support much higher levels of social functioning.

The towers and the skytrain need not apply.