Shadow studies often get lost amid the seemingly more pressing issues related to current urban planning and design. However, the relevance of shadow studies has only grown, as cities face increasingly complex challenges related to density, sustainability, and livability. Ultimately, well-designed neighbourhoods strike a balance between built density and access to sunlight as a means of ensuring that residents enjoy comfortable, just, and healthy living conditions. Shadow studies play a crucial role in achieving this balance. So, let’s remind ourselves about where they came from and why their neglect by developers, architects, and planners should be questioned.

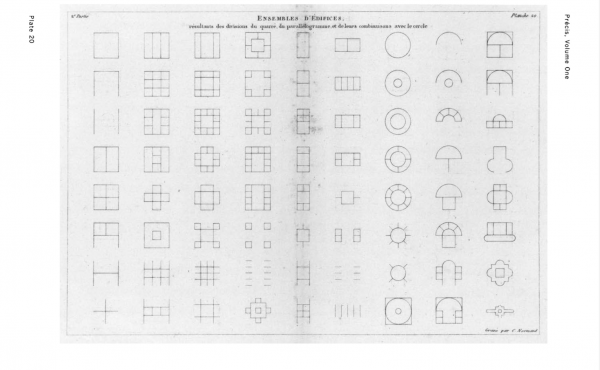

A genuine look at the history of shadow studies and cities would trace things back to the earliest human settlements and vernacular architecture, where people intuitively oriented their structures to maximize sunlight exposure for warmth and illumination. It is no surprise that humans need light, physiologically and psychologically. Ancient civilizations across every culture recognized the importance of sunlight in architecture and settlements, accordingly. This is evident in the orientation of sacred temples, amphitheatres, public squares, and other spaces designed to capture the sun’s rays during specific times of the day.

During these early days, the “regulation” of solar control varied across cultures. However, the birth of sun-shadow regulations—as with all regulations—is connected to religious and cultural values systems related to proper behaviour. That is, shadowing and access to the sun were an issue of ethics. For example, in Arabic-Islamic tradition, an initial building allowance in early settlements that allowed people to build as high as they wanted within their “air space” was overturned once it was found that people were using it to harm neighbours intentionally by taking away access to sun and air.

It’s worth noting, however, that solar control strategies were climate-dependent. For example, in many hot environments, shade and shadow were intentionally “designed” into cities—through elements such as courtyards and narrow streets—to provide relief from the powerful sun. As such, shadowing was seen as something positive. Conversely, as people and their settlements moved into colder climates, maximizing sun exposure for warmth and light became paramount for survival.

Equally important is that for the majority of urban history, solar access was somewhat self-regulating since building heights were limited by construction systems. So, in parts of the world where sun access was desirable, the “harm” done to individuals and the public through shadow creation was constrained by building technologies.

The history of shadow studies in contemporary urban planning can be traced back to the mid-20th century when cities experienced rapid growth. With the rise of urbanization and high-rise construction, shadow studies became essential tools for addressing the challenges of daylighting, solar access, and urban microclimates. As skyscrapers and high-rise buildings began to reshape urban skylines in sun-desiring cities, concerns arose about the potential negative impacts of shadows on streets, parks, and public spaces. In response, planners started incorporating shadow studies into the development approval process to assess the sunlight access and microclimate effects of proposed projects.

One notable example of the significance of shadow studies in urban planning is the case of New York City’s zoning regulations. In response to concerns about the excessive overshadowing caused by tall buildings, particularly in Manhattan, the city implemented zoning laws in the early 20th century to limit building heights and preserve sunlight access to streets and parks. These regulations were informed by detailed shadow studies conducted by architects and planners to balance density with livability. A city of shadow-dwellers was unanimously seen as negative.

Although these contemporary regulations attempted to detach themselves from religious and behavioural codes of conduct, their ethical roots remained the same: in locations where the sun is desirable, the unsaid underlying reason behind the shadow study regulations is that solar access is an ethical right, and any infringement of this basic human need is necessarily undesirable.

Let’s dig into this a bit more as it relates to cities in colder climates where access to the sun is important.

One of the key considerations in contemporary shadow studies is the concept of solar access—that is, the availability of sunlight to buildings and public spaces. Based on the most recent research, solar access has a wide variety of benefits to city inhabitants, including but not limited to the following::

Health and Well-being

a. Mental Health

- Sunlight Exposure: Access to natural sunlight positively impacts mental health by helping to regulate circadian rhythms and mood.

- Reduced Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD): Sunlight exposure can mitigate the symptoms of Seasonal Affective Disorder, which is prevalent in areas with limited sunlight.

- Improved Emotion Health: Sunlight exposure has been linked to improved emotional health, leading to a greater sense of well-being and happiness.

b. Physical Health

- Vitamin D Production: Sunlight exposure stimulates the body’s production of vitamin D, which is essential for bone health, immune function, and reducing the risk of certain diseases.

- Improves Sleep: Exposure to natural sunlight during the day can help regulate sleep patterns, leading to better sleep at night.

- Reduced Stress: Sunlight exposure can reduce stress levels and lower blood pressure.

Promotion of Green Spaces

a. Urban Forests and Parks:

- Strategic Location: Shadow studies identify suitable locations for urban forests, parks, and green corridors, which provide shade, reduce temperatures, and improve air quality.

- Cooling Effect: Parks and green spaces created through shadow analysis act as “cool islands,” providing relief from high temperatures and mitigating the urban heat island effect.

b. Green Roofs and Walls:

- Strategic Placement: Shadow studies inform the placement of green roofs and walls to maximize their effectiveness in absorbing heat and reducing the urban heat island effect.

- Temperature Reduction: Green spaces created through shadow analysis absorb heat, lower temperatures, and enhance air quality.

- Increased Evapotranspiration: Green spaces increase evapotranspiration, which cools the surrounding air, reducing the overall temperature of the area.

Optimized Building Design

a. Shading:

- Strategic Placement: Shadow studies help identify areas where shading can be strategically placed to reduce direct sunlight exposure on building facades, sidewalks, and streets.

- Use of Overhangs and Awnings: By using overhangs, awnings, and other shading devices, architects can minimize solar heat gain, reducing the need for air conditioning and lowering energy consumption.

- Tree Planting: Shadow studies inform the strategic placement of trees, which provide natural shade and help cool the surrounding environment.

b. Building Materials:

- Reflective Surfaces: Shadow studies guide the use of light-colored and reflective building materials to reduce the absorption of solar radiation and minimize heat retention.

- Cool Roofs: Analysis of sunlight and shadow patterns helps determine the most effective locations for implementing cool roof technologies, which reflect more sunlight and absorb less heat than traditional roofs.

Street Design and Infrastructure

Urban Design

- Street Orientation and Width: Shadow studies inform street orientation and width to maximize shading and promote natural ventilation, reducing the overall temperature.

- Pedestrian Comfort: By reducing direct sunlight exposure on sidewalks, streets, and public spaces, shadow studies enhance pedestrian comfort and encourage active transportation.

Water Features

- Strategic Placement: Shadow studies inform the placement of water features, such as fountains and ponds, which have a cooling effect on the surrounding environment through evaporation.

Energy Efficiency and Sustainability

Reduced Energy Consumption

- Daylighting: Solar access reduces the need for artificial lighting during the day, leading to significant energy savings.

- Passive Heating: Sunlight can provide passive heating during colder months, reducing the demand for space heating.

- Cooling Load Reduction: Proper solar access can minimize the need for air conditioning during warmer months by allowing for natural ventilation and reducing the urban heat island effect.

Promotion of Renewable Energy:

- Solar Power Generation: Solar access enables the installation of photovoltaic panels on buildings, contributing to the generation of clean, renewable energy.

Economic Benefits

Increased Property Value:

- Desirability: Properties with good solar access are more desirable, leading to increased property values.

- Lower Energy Costs: Homes with efficient solar access have lower energy costs, making them more attractive to potential buyers.

Environmental Benefits

Urban Heat Island Mitigation

- Heat Reduction: Solar access helps mitigate the urban heat island effect by allowing green spaces and buildings to absorb and reflect less heat.

- Improved Air Quality: By reducing the need for air conditioning, solar access contributes to lower energy consumption, which in turn leads to reduced greenhouse gas emissions and improved air quality.

Social Equity

Equitable Access:

- Equal Access to Sunlight: Proper urban planning and solar access considerations ensure that all neighborhoods have equitable access to sunlight, promoting social inclusion and well-being for all residents.

- Enhanced Public Spaces: Parks, plazas, and streets with good solar access become vibrant community spaces, fostering social interaction and a sense of belonging.

- Addressing Heat Vulnerability: Shadow studies identify areas that are particularly vulnerable to heat stress, allowing planners to implement targeted strategies to improve sunlight and shade access for vulnerable populations. This is particularly relevant for cities that are experiencing extreme heat events during the hot months of the year, such as heat bubbles.

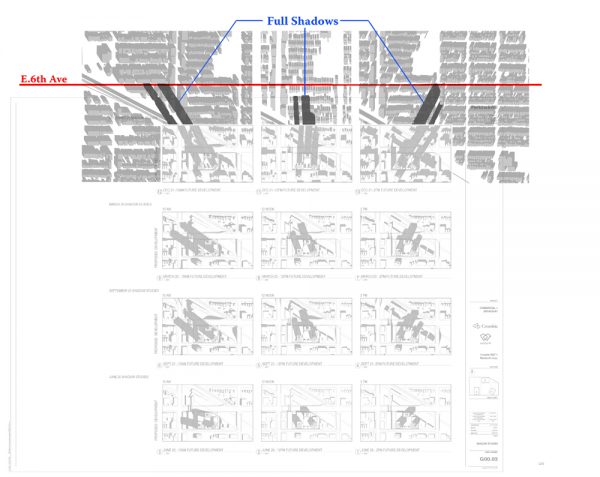

It is because of this wonderful variety of benefits that many municipalities implemented and continue to include shadow studies in their regulations. Typically, cities ask designers to see the shadows on summer and winter solstices (the shortest and longest shadows, respectively), as well as the two equinoxes in March and September, capturing shadows cast at 10 am, 12 noon, and 2 pm on those days. These dates are carried over from the days before computer modeling—when designers had to draw manually—and give one a sense of the shadow extremes along with their midpoints. This allowed people to mentally “fill in the blanks” between those dates.

However, given that advanced simulation software is the norm for architects today, it is well within reason for municipalities to ask for full digital shadow animations for the entire year. This will take the guesswork out of the process and allow people to accurately assess the full impact of buildings on their surrounding environment, assuming the model is constructed correctly. Current technologies even allow for this to be done at the scale of the city and not just the lot.

Yet, despite the benefits, developers, and architects often try to find ways to undermine shadow studies. From creating inaccurate photorealistic renderings and using image frames to cut out true shadow lengths to simply providing drawing packages that exclude the winter solstice (the day with the longest shadow), there is no shortage of ways people have tried to subvert the regulations and the public good from which they were born. Several local examples of this can be found in Some Useful Resources below. At best, this is done out of ignorance, at worst these are intentional tactics used to lie to municipal officials and the public—profiting the few at the expense of the many.

Ultimately, shadow studies were born from values recognizing that equitable access to sunlight and daylighting in urban environments is an ethical issue prioritizing human well-being. Related regulations attempt to preserve this for future generations. All the fancy advanced digital tools and simulation software used to model the intricate interplay of sunlight, shadows, and urban form, serve this simple end. In this way, any attempt to undercut shadow studies can be seen as an attack on creating a just and livable city.

****

In summary:

- Shadow studies can be traced back to the earliest human settlements, where people intuitively oriented their structures to maximize sunlight for warmth and light.

- Although the “regulation” of solar control varied across cultures, they were founded on values concerning proper “neighbourly” behaviour and considered an issue of ethics.

- Solar control strategies vary with climate. In hot environments, shade and shadow were often intentionally “designed” into cities to provide relief from the powerful sun. In cold climates, attempts were made to maximize sun for warmth.

- For the majority of urban history, solar access was somewhat self-regulating as buildings were limited by construction technologies that kept their heights quite low.

- With the rise of urbanization and high-rise construction in the 20th century, concerns arose about the potential negative impacts of shadows on people, streets, parks, and public spaces. In response, planners started incorporating shadow studies into the development approval processes to assess the sunlight access and microclimate effects of proposed projects.

- Despite the large changes in urbanization and building technologies brought by the 20th century, the ethical roots of shadow studies remained: that is, solar access is an ethical right, and any infringement of this basic human need is necessarily undesirable.

- The concept of solar access—the availability of sunlight to buildings and public spaces—is critical to shadow studies. This, in turn, has a wide variety of benefits touching on issues such as mental health, the promotion of green spaces, social equity, optimizing building design, promoting energy efficiency and sustainability, street and infrastructure design, property values, urban heat island mitigation, and social equity.

- Despite its many benefits, developers and architects often try to find ways to undermine shadow studies—from creating inaccurate photorealistic renderings to providing incomplete information. This is done out of ignorance or intention, profiting the few at the expense of the many.

- It is common for regulations to ask for shadow studies for set times of the year—the winter and summer solstices, as well as the equinoxes—allowing for people to mentally “fill in the blanks” between these dates, it is well within reason for municipalities to now ask for full digital shadow animations for the entire year, given that advanced simulation software is the norm for architects today,

- Shadow studies were born from values recognizing that equitable access to sunlight and daylighting in urban environments is an ethical issue prioritizing human well-being. As such, any attempt to undercut shadow studies can be seen as an attack on creating a just and livable city.

Some Useful Resources:

- What are Architectural Shadow Studies and Why Are They Important?

- ArchDaily – The Role of Shadows in Vernacular Architecture

- NYC shadow study regulation document

- NY Times: Mapping the Shadows of New York City: Every Building, Every Block

- Spacing Vancouver – Deconstructing Visuals 2.0

- City Conversations – A Shadow of a doubt

- City Hall Watch – Incorrect shadow studies for 1551-1581 W7th Ave rezoning (Acton Ostry Architects), and case study at 228-246 E Broadway & 180 Kingsway (same company). Big problems with renderings vs reality in the Broadway Plan area.

- City Hall Watch – Ground Truthing Shadows

- City Hall Watch – How accurate are the shadow studies of the proposed 1477 W Broadway tower? See a comparison against a few different sources and judge for yourself.

- At 215-229 East 13th Avenue, a 21-storey tower rezoning. Online Q&A April 10-23. Renter demoviction. Breaks Broadway Plan solar access rules for Main Street. False shadow studies. JTA Dev Con.

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning.

One comment

In Canada, I’m not sure the solstices and equinoxes are the most effective times to do shadow studies. Most places are in shadow anyway in December, there’s little shadow in June (and it might be welcome). And the equinoxes aren’t especially significant for, say, growing things. It might be more significant to test for sunlight in April/May, for example.