What is Transit-Oriented Development and what are its benefits and drawbacks?

Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) has become so common within urban planning circles that many preach it is a “universal truth” of sound planning decision-making. Within the North American context, the term has become synonymous with mixed-use towers around transit stations, with advocates touting its many ‘sustainable’ characteristics. This “default” mentality, however, hides a lot of important information about the concept of TOD. As always, let’s dig into interpreting TODs—a little bit of its history, its principles, as well as its benefits and drawbacks.

First and foremost, it’s important to understand that in its broadest sense “transit-oriented development” is much, much older than its current expression. The practice of people and activities gathering around heavily trafficked corridors and nodes is thousands of years old. It can be seen in countless ancient settlements around the world. Historically, people and commercial activities naturally migrated to locations where there were a lot of people, and a lot of people happened to be along corridors that connect to significant locations and the intersections of important corridors. It’s a fundamentally straightforward, pragmatic idea that didn’t need any hierarchical ‘urban planning’ as currently practiced at all.

Many credit the origins of Transit-Oriented Development in the modern sense to Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City movement in England during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Imagined in response to the overcrowded and problem-ridden cities of that time, Howard advocated for the creation of clusters of self-sufficient ‘planned’ communities that would provide a healthier, more balanced environment for residents each of which would be connected by roads and rail lines.

The rise of the automobile in the 20th century saw a drastic shift towards sprawling, car-oriented development. However, this trend began to change in the 1960s and 1970s, as rising oil prices and growing concerns about air pollution and traffic congestion led to renewed interest in TOD. During this time, a number of cities in Europe and North America began to implement TOD principles in their urban planning and development, often as part of larger efforts to revitalize declining inner-city neighborhoods.

However, it was during the 1980s and 1990s, that TOD took off, thanks to American architect, urban designer, and town planner Peter Calthorpe, who is often credited with popularizing the concept of TOD and helping to establish it as a mainstream approach to urban design and planning that countered the negative effects of low-density suburban development. His work aligned with increased investment in public transportation systems and growing awareness of the benefits of compact, walkable communities. Today, TOD continues to be a widely-adopted concept in cities around the world, and is seen as a key strategy for creating sustainable, livable communities in the 21st century.

But what is Transit-Oriented Development exactly?

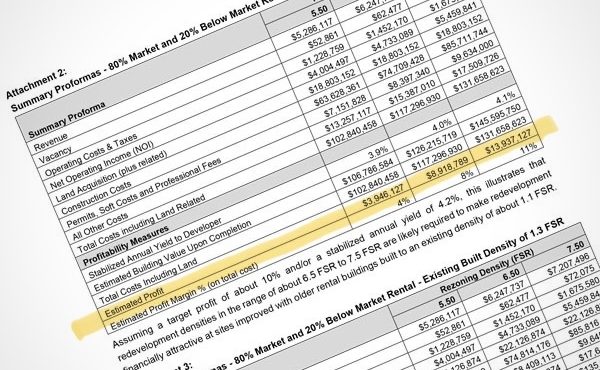

In short, TOD emphasizes the creation of compact, high-density, walkable, mixed-use communities centered around public transportation systems. Its principles are well summarized by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy in the graphic below.

Like many popular urban planning trends and theories, however, a large part of its usefulness and power comes from the fact that it can be interpreted in several ways. This is also its largest shortcoming. We’ll get into both starting with some of the key potential benefits of TOD:

- Improved public transportation: In prioritizing the integration of public transportation and development, TOD can result in improved access to public transportation and more efficient, reliable, and affordable transportation options.

- Increased access to jobs and services: By promoting compact, mixed-use development patterns TOD residents can have convenient access to jobs, services, and amenities, reducing the need for car travel and promoting walkability.

- Increased affordability: TOD may provide more affordable housing options, as the concentration of development near public transportation can allow for more efficient use of land and reduces the need for expensive transportation infrastructure. Before affordability advocates close the page in glee, keep reading to see how TOD can also decrease affordability in a community.

- Improved health: TOD can promote physical activity by providing residents with safe, easy access to public transportation. This may result in improved health and reduced rates of obesity and other health problems.

- Environmental benefits: Air and other pollution can be reduced, natural resources conserved, and greenhouse gas emissions curbed through TOD by promoting “sustainable” transportation and development practices.

As mentioned, TOD ultimately emphasizes the creation of compact, high-density, walkable, mixed-use communities centered around public transportation systems. Within this context, walkable is typically defined as an area within a 5-minute walking distance (approx. 400m-800m of the transit node). Mixed-use, in turn, is often interpreted as developments that mainly mix commercial and residential uses, with other supplementary uses, at times. While questioning these assumed definitions and assumptions is certainly worthwhile, the most troublesome issue focuses on the meaning of compact and high-density since this brings us to the many confusions around “density” that we’ve covered elsewhere in S101S.

Although Transit-Oriented Development and density are closely related, they are different in important ways. While TOD emphasizes the creation of compact, high-density, walkable, mixed-use communities around transportation nodes, density itself refers to the number of people in a given area. Let’s break their relationship down a bit further.

By encouraging compact, high-density, mixed-use development patterns around public transportation, TOD promotes the efficient use of land and the reduction of sprawl. This can result in “higher” population densities, with more people being able to live and work in a given area. “Higher” densities near public transit may also support (but not necessarily) the viability of public transit systems, as more people are located within close proximity to these systems, making them more convenient and accessible. Additionally, “higher” densities may help to support local businesses, as well as increase the availability of amenities and services for residents.

All good things at a glance, no doubt. However, it’s important to note that the definitions of compact and high density are left open within the TOD concept. So, not all TODs result in “high densities”, and not all “high-density” developments are TODs. TOD is a design concept that prioritizes the integration of land use and transportation, while density is simply a measure of population and building intensity. The relationship between TOD and density will vary depending on a number of factors, including the specific development context, local zoning regulations, and market conditions. So, Barcelona’s midrise Eixample urban fabric is as valid an expression of TOD as Toronto’s high-rise forest around Yonge and Eglinton. Ultimately, context matters.

This will allow us to put the myth of TOD, density, and building type to bed: specific building types (i.e. towers) are not required to create a successful TOD. Remember, densities may or may not relate to specific building type. That developers, transit authorities, and municipalities often connect TOD and towers as a necessary duo is, at best, ignorant and at worst, deceitful.

This also brings up questions about whether there is an upper limit to density for a site in compliance with TOD. Is there such a thing as a site having too much density, or say too many towers? TOD principles do not answer this explicitly, often giving TOD-tower advocates a blank slate to answer it in any way they wish—that is “the more towers, the more transit-friendly it is.” Again, this is not necessarily the case and such sentiments are worth questioning very critically.

Now, TODs are not all sunshine and rainbows…. apologies in advance to all those die-hard TOD advocates. Like any large-scale urban development project, Transit-Oriented Development can have both positive and negative impacts. While TOD can bring many benefits, such as improved public transportation, increased access to jobs and services, and so on, it can also have negative impacts on communities: impacts that are too often actively avoided by municipalities, developers, and similar parties. These include but are not limited to:

- Decreased affordability and increasing property values: TOD can lead to gentrification by increasing property values and attracting higher-income residents to traditionally lower-income neighborhoods. This can and has contributed to decreased affordability.

- Displacement of low-income and marginalized communities: TOD can lead to the displacement of long-time residents, particularly in areas with rising property values and limited affordable housing options. Worth noting is that as unaffordability increases, displaced populations are not confined to low-income populations.

- Social and cultural homogenization: TOD can lead to the loss of local character and cultural diversity, as neighbourhoods are transformed (sometimes radically) by new construction as well as the arrival of new residents and businesses.

- Increased pressure on existing infrastructure: TOD projects can increase demand for public services such as schools, parks, and health care, which can be difficult for communities to accommodate.

- Unequal distribution of benefits: TOD can benefit some communities more than others, with more affluent communities often reaping the majority of the benefits, while low-income communities may experience the negative impacts of TOD more acutely.

It is critical to understand that the social impacts of TOD vary greatly depending on the specific context and circumstances of each project. Minimizing the negative impacts of TOD and ensuring that it benefits all members of a community, often requires involving all stakeholders, including low-income and marginalized populations, in the planning and decision-making process.

Equally important is actually listening and meaningfully responding to stakeholder feedback. I’ve taken part in many sessions where communities who welcome transit and increased density, but do not want towers, are vilified and wrongfully accused of not supporting TOD. Worth mentioning again: TOD principles do not specify a building type or density numbers. Context matters. A more appropriate response is to explore alternative building types that fit community desires while specifying and maintaining “higher density” targets in keeping with the principles of TOD. This involves taking into account more comprehensive approaches to growth and densification at the neighbourhood- and city-wide scales instead of focusing on “packing in” people on a single lot or small handfuls of sites.

Last but not least, TOD projects should incorporate strategies to mitigate the destructive impacts of gentrification and the displacement of long-time residents in the area. Ultimately, one wants to ensure that the benefits of TOD are equitably distributed.

In summary:

- Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) is common planning practice emphasizing the creation of compact, walkable, mixed-use communities around transportation nodes and corridors.

- Despite its pervasiveness, TOD principles can and are interpreted and misinterpreted. As such, in North America, TOD has wrongfully become synonymous with mix-used tower developments on and around transit nodes and corridors.

- The practice of people and activities gathering around heavily trafficked corridors and nodes is thousands of years old, prior to “urban planning” as currently practiced. It simply makes pragmatic sense and offers more than the sum of its parts.

- The benefits of TOD include: improved public transportation, increased access to jobs and services, increased affordability, improved health, and environmental benefits.

- The negative effects of TOD include: decreased affordability and increasing property values, displacement of low-income and marginalized communities, social and cultural homogenization, increased pressure on existing infrastructure, and unequal distribution of benefits.

- While emphasizing the creation of compact, high-density, walkable, mixed-use developments centered around public transit, the definitions of compact, high–density, walkable, and mixed-use within the TOD concept are open to interpretation. The lack of definition around compact and high density is particularly troublesome as it causes a lot of confusion in its relationship to density and building type—concepts confusing in their own right.

- Although TOD and density are closely related, they are different in important ways. TOD emphasizes the creation of compact, high-density, walkable, mixed-use communities around transportation nodes, while density itself refers to the number of people in a given area

- Not all TODs result in “high densities”, and not all “high-density” developments are TODs. Context matters.

- TOD principles do not specify a building type (i.e. towers) or density numbers. Successful TOD can and has been done without very high-density building types (i.e. residential towers). Again context matters.

- Minimizing the negative impacts of TOD and ensuring that it benefits all members of a community, requires involving and listening to ALL stakeholders (including low-income and marginalized populations) in the planning and decision-making process, incorporating strategies to mitigate gentrification and the displacement of long-time residents in the area, and ensuring that the benefits of TOD are equitably distributed.

Some Useful Resources:

- Transit-oriented Development Wikipedia

- Principles of TOD – Institute of Transportation and Development Policy

- Peter Calthorpe – 7 Principles for Building Better Cities (Ted Talk)

***

Related pieces in the S101S:

- S101 Series: Introduction and Call

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Why is it so Confusing?

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Net vs Gross Density

**

All pieces in the S101S:

- S101 Series: Introduction and Call

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Why is it so Confusing?

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Net vs Gross Density•

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: FSR, Building Setbacks and Height Regulations

- S101S : Understanding Shadow Studies: Why They Matter –

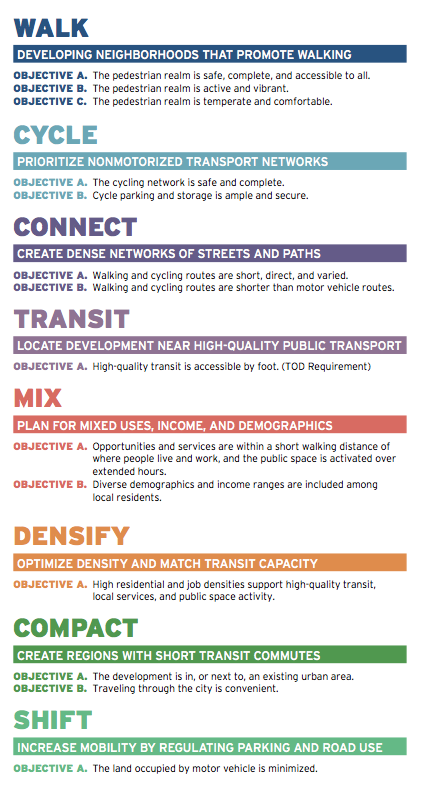

- S101S: What’s a Development Pro Forma—And Why Should you Care?

- S101S: Defining Public Space: The Basics

- S101S: Understanding Affordable Housing: The Trickle-Down Theory of Housing – Myths and Realities

- S101S: Describing Building Types: Why They Matter

- S101S: Describing Building Types: Formal and Use-Types

- S101S: Explaining Transit-Oriented Development: Benefits and Drawbacks

*

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.