What is Floor Space Ratio (FSR) and how does it interact with building setbacks and height regulations to create building forms and the ‘look and feel’ of a place?

Having covered why residential density is it so confusing and the difference between net and gross density, it’s worth going into how regulations related to density result in building forms. Now there are a lot of regulations used by municipalities dedicated to manipulating buildings and urban form, but none more influential than the interaction between Floor Space Ratio (FSR), building setbacks, and height restrictions. So, let’s take a closer look at each of these and how they work together to manipulate building forms, starting with the one many find confusing FSR.

Floor space ratio (FSR), also known as the “Floor Area Ratio” (FAR) or “Gross Floor Area” in certain municipalities, is a measure used to ensure that buildings are of a certain size relative to the size of the parcel on which they sit—more specifically, how much total floor area (from all floors) a building may occupy on a particular parcel of land. As the name suggests, FSR is often expressed as a ratio or a percentage of the lot area and is calculated by dividing the total floor area of a building by the parcel.

A simple example will best serve to see how this works: a site that has an FSR of 1.5 means that a building can have a total floor area that is 1.5 times the area of its lot. So, if a parcel has an area of 1,000 square meters (about 10,800 ft²), the maximum allowable floor area of a building built on that lot is 1,500 square meters (approximately 16,100 ft²). Similarly, a site with an FSR of 1.0 means that a maximum allowable floor area of a building built on that lot is equivalent to the area of the lot. Remember, the maximum allowable floor area is for all floors in the building.

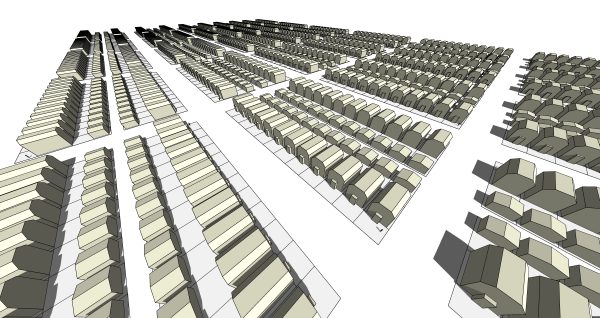

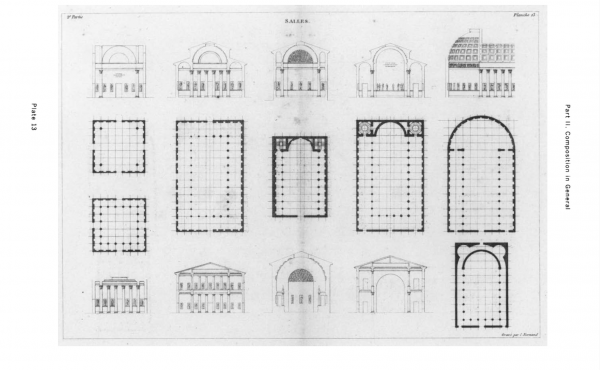

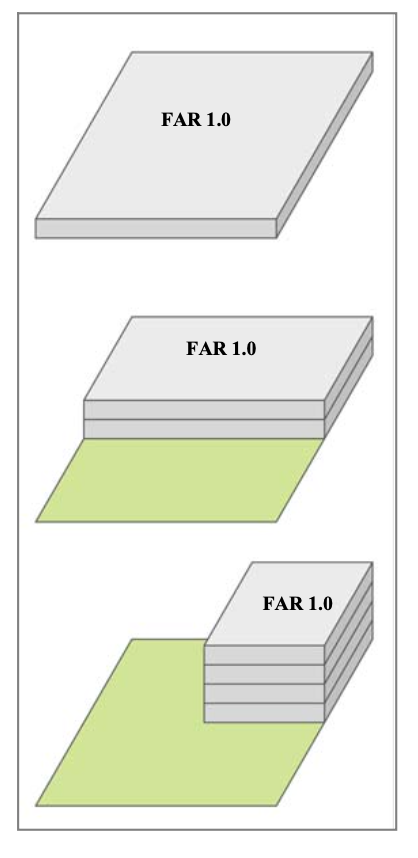

What’s important to understand is that, since FSR only gives the maximum allowable floor area, buildings can take many different configurations and geometries while meeting this regulation. The diagram below different configurations a building area can take with an FSR of 1.0.

As we can see, FSR can and does affect the height, mass, and overall design of buildings, but it needs to team up with building setbacks and height regulations to limit all the possibilities. As the name suggests, setback regulations determine the minimum distances that buildings must be set back from the property line. This can be used to create space between buildings for light, air, privacy, and separation from other properties or streets, over and above providing for landscaping, walkways, and other amenities. Setback requirements can be as detailed as desired and vary depending on the district, lot size, and building purpose. Height regulations are the most straightforward of the three, limiting the height a building can have.

In light of the above, it should be clear how the interaction between FSR, building setback regulations, and height restrictions can significantly impact the built form of a community: the three regulations working together to drastically limit possible building forms. In general, if the FSR is high, setbacks are low and height allowances are high, then buildings can be built close to the property line, tall and massive. On the other hand, if the FSR is low, setbacks are high and height regulations low, then buildings will be shorter and set back from the property line, creating more open spaces.

In North America, most residential areas have FSR values well below 1.0, since single-family homes continue to be the dominant residential building forms across our cities. As a local reference, Vancouver’s Residential – Single Detached House (RS-1) zones have an FSR of 0.6—meaning that the maximum floor area of a building can have is 60% of the lot area. With a standard lot of 33’x122’ (4,026 sq.ft), this means that the maximum allowable floor area for a typical Vancouver lot is about 2,400 sq.ft.

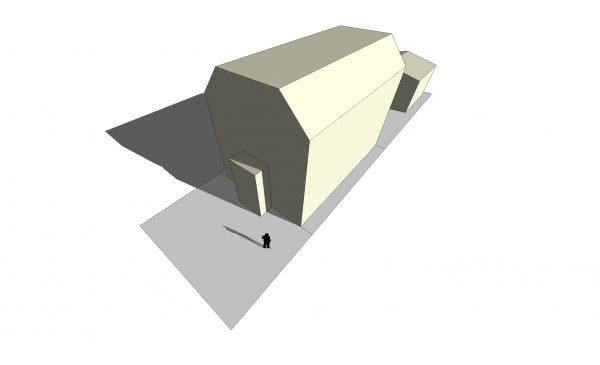

Let’s end by looking at the on-the-ground effects of this regulatory interaction. Below is an image of the allowable building envelope of Vancouver’s Residential – Single Detached House (RS-1) from a few years ago. It is largely the same now and although this is the culmination of all regulations, FSR, setbacks, and height regulations are the main contributors to its form. This is a particularly instructive example since the setbacks incorporate an angle along the upper corners, the implications of which will be very clear soon.

This ultimately resulted in countless homes like these:

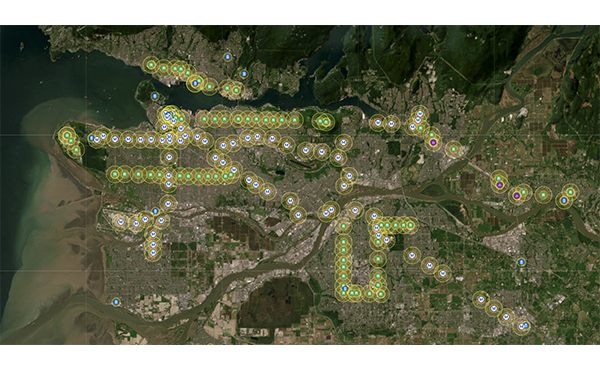

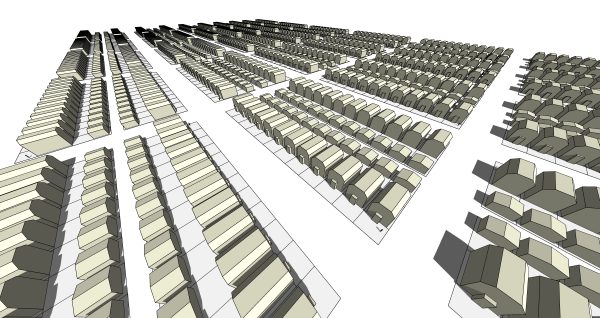

The power of these regulations, however, is only truly understood when we appreciate that they cover vast tracts of land and not just single lots. In that they dictate the forms of building and their relationship to the streets, these regulations affect the experience—the general “look and feel”—of streets and blocks. With this in mind, below is what an RS-1 neighbourhood in Vancouver would look like at the regulatory level:

And below is one example of the ‘look and feel’ of the regulation multiplied across many lots in the city. There are many areas where both sides of the street are identical.

This brings up many important questions about the role of municipalities and the, often hidden, values embedded within regulations they create (the role of values being something we’ll touch on in another S101S piece). In many cities, the influence property owners and designers have over buildings is much more limited than most people realize, as anybody who has ever built or renovated a house will readily admit. Cities are now largely “designed” by policy writers. Where once planners and politicians were considered “indirect” agents of change—versus developers, architects, and builders—the line between the indirect and direct has become increasingly blurry.

Consequently, few urban planners and policy-makers—let alone council members and other powerful decision-makers—have design-related education, and as a result, often have great difficulty understanding the connection between the abstract math used in policies they create and vote on, and their built implications. Who wouldn’t? This leads to countless poor decisions and errors at all scales of urban planning and design.

This is further fuelled by municipalities continuously arguing their central roles as focusing on public safety and health, distancing themselves from the reality that they are front-and-centre on ‘design’ decisions about the city, including architecture and building forms, over and above critically important land use decisions. In some areas, even the building finishes and plants that property owners are allowed to put in their yards are regulated. This often serves to deflect responsibility to others (architects and developers being the easiest targets) and hide the fact that there is a “design”—dare I say “aesthetic”—value system behind their decisions….a value system that is, not always, but often intimately tied to economic agendas.

Motives notwithstanding, here is what we can take from this: regulatory decisions—such as floor space ratio (FSR), building setback regulations, and height restrictions—are not value-neutral and we need to vigilantly question them critically at all times.

In understanding the interaction between FSR, building setback, and height regulations, it’s hopefully clear that within the contemporary North American city, those that control policies and regulations ultimately control the overall “look and feel” of a place. Everything from our single-family neighbourhoods to the skyscraper forests we see are largely ‘designed’ by urban planners and municipal officials without design or architectural experience (somewhat randomly) tweaking numbers prior to any pencil hitting paper.

****

In summary:

- Building forms and density are controlled by a variety of regulations, the most influential being Floor Space Ratio (FSR), building setbacks, and height regulations.

- Floor space ratio (FSR) regulates how much total floor area (from all floors) a building may occupy on a specific parcel of land. It is often given as a ratio or percentage.

- Many different building forms and configurations are possible while conforming to Floor space ratio (FSR) regulations.

- Setback regulations determine the minimum distances that buildings must be set back from the property line, while height restrictions limit how high a building can be built.

- Taken together floor space ratio (FSR), building setback regulations, and height restrictions serve to drastically limit possible building forms.

- Floor space ratio (FSR), building setback regulations, and height restrictions largely control the overall “design” of areas within the city. In this way, regulators are mainly responsible for the “look and feel” of a place.

- Most urban planners and municipal officials do not have design or architectural backgrounds and have trouble understanding the built implications of the formulas and numbers that they regulate.

- Regulatory decisions about floor space ratio (FSR), building setback regulations, and height restrictions are not value-neutral and often reflect the (hidden) values of policymakers. This requires us to critically examine and question the values behind regulations continuously.

Some Useful Resources:

- Demystifying Density: A comparison of different forms of density in five case studies in the Greater Vancouver Region by Patrick Condon, Jone Belausteguigoitia, Sara Fryer, and Kristi Tatebe

**

Related pieces in the S101S:

- S101 Series: Introduction and Call

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Why is it so Confusing?

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Net vs Gross Density

*

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning.