Why is an understanding of building types important to urban planning and design? What aspects of planning are they connected to?

Given that urban planning involves the systematic organization and design of the built environment, building types are an important part of the planning puzzle. Many wrongly assume, however, that how building types are defined, understood and used is a straightforward matter. Nothing can be further from the truth. We’ve already seen how specific building types are confused with density and Transit-Oriented Development, for example. So, I think it’s time to tackle this issue head-on. But unpacking this will take time—well beyond one piece. This being the case, let’s start with a little history and take a step back to look why building types matter.

Beginning with basics: building type is an idea that has a rich architectural history. Although we will be focusing on the latter, typologies, broadly speaking, are simply classification systems and, as such, are not confined to the architecture discipline. Many others, like biology, use the idea of types due to its inherent usefulness: a usefulness that come from its abstraction. That is, building types are abstract. But the foundations typological studies lie in the fact that they try to establish a system of analysis that breaks the city down into fundamental components evident in all settlements, regardless of culture, location, or history.

It may seem obvious, but it’s important to clearly state that building types include all buildings. Architects often like to differentiate “Architecture” with a capital “a” from all other buildings, of “architecture.” Building types see no such distinction. The ordinary and extraordinary buildings are of equal value.

Although the exact origins of the concept of architectural typology is unknown, it clearly has ancient roots. Early urban civilizations developed distinct building types based on their needs and categorized them, accordingly. It’s believed that the earliest categorization system simply differentiated “house” and “non-house.” Arguably, this is where our confusion begins: since the form of the house and its use were fused together under the “house” label. We’ll loop back to this when we discuss formal versus use-types in a later piece. For now, let’s get back to some important history and context.

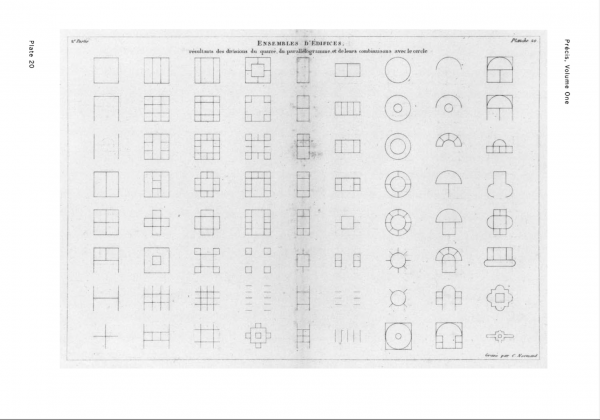

Over time, as more complex urban cultures developed, the “non-house” category expanded and diversified. In came everything from temples to basilicas, schools to universities, libraries to community centres, museums to art galleries, barns to airports. The list goes on and on, as we know. The ‘house’ followed suit, exploding to include everything from the Japanese Machiya to the Roman villa, single-family homes to apartments, townhouses to laneway homes, condos to cottages, cabins and bungalows, duplexes to farmhouses, to name only a handful. I won’t even touch stylistic variants, like the “American Craftsman”, “Greek Revival” or “Neo-classical.” Academically, many consider Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand‘s influential book Précis des leçons d’architecture données à l’École royale polytechnique —written in the early 1800s—to be first official text that systematized architectural building types.

Needless to say, contemporary cities are storehouses (pun intended) of building type. Hence, their importance to urban planning. It’s very important to note, however, that individuals and institutions have very limited control over the design and evolution of building types. That is: building types emerge and evolve in response to a highly complex set of social, cultural, environmental and economic conditions. Individuals—such as designers— and organizations can and do attempt to guide them using everything from imaginative proposals to regulations, but ultimately only the broader socio-cultural collective can invent and adapt building types to their specific set of needs over time.

This points to an important insight: building types can only be manipulated by making changes to the conditions from which they arise, not the building type itself. This is no small feat, however, since the conditions are complex and entangled.

This being the case, building types are very unpredictable. Although it’s easy to assume that those intimately associated the designing the built environment—architects and designers, for example—drive building type creation and development, this is not the case. No single person, discipline or organization can be credited. The airport or strip mall as building types, for example, were born in response to a myriad of factors; their evolution the result of a complex web of people contributing from a wide array of fields alongside the transformation of larger societal values and behaviours.

This can be frustrating because the “best” or “newest” solutions are not necessarily those “chosen” by society-at-large to build. What is defined as the “best” changes with time, after all. This is made more complicated by the fact that buildings take a lot of time and money to construct and are built of materials that longer lasting than most products. So, buildings tend to lag behind technological and cultural value shifts, fossilizing past patterns.

So, the trenches of the architectural history books are filled with interesting, innovative building type experiments that are one-offs, went obsolete, or were simply never built for one reason or another. There are a number of inventive residential towers built in the world today—let alone proposed on paper!—that do well to address the many social and environmental concerns associated with the building type, for example, but they remain one-of-a-kind. They are currently dead-ends in the typological evolutionary tree.

It’s easy to believe that the most recent types are part of a linear progression towards the “best” solution and that these will be with us from here on in. Too frequently, for example, I hear people of all stripes stating with complete conviction that residential towers are the future of cities. The unpredictable nature of building types places such sentiments in the category of purely unfounded speculation. Like with any product, the newest types are the least tested, and ultimately offer us little insight into their future success. If towers are still around in 200 years—let alone 1000 years—they will be surely be radically different than the ones we see around us today. But residential high-rises are only one of countless new building types born over the past century or two. If history is any indication, only a handful will have significant longevity—most finding their place alongside temples and blacksmith shops of the past. A humbling thought.

Now, certain building types become obsolete more quickly that others—particularly those that are inflexibly tied to specific uses and functions. It’s important to noting, as well, that types can be regulated out of existence through policies, for better or worse. This shows how certain people and organizations can and do influence building type.

With this in mind, it’s worth noting that the architectural history books are also filled with types—and proposed types—that have been revived or re-envisioned. Architecture’s “lag” mentioned above, finds its positive side here. There are many examples of not only single buildings but full communities being revived after laying in ruins for decades.

Equally important, there are are a lot of building types that have stood the test of time. Some, like the courtyard house, have evolved with urban civilization for hundreds or even thousands of years. Building types that have longevity should be on people’s radars given that they have withstood countless societal and technological revolutions. Simply put: they have stood the test of time. Why and how is of particular interest, and perhaps we’ll cover some of these special types in future pieces.

For now, it’s worth noting that given that building types are born from social, economic, and environmental factors, they also have implications across each of these categories, beyond simply shaping the character, function, and overall layout of cities. Let’s look at some of the main aspects of the contemporary city that building types are connected to:

- Architectural Character & Aesthetics: Arguably, the most direct and easily understood, building types contribute to the visual identity of a neighbourhood and city. Certain building types may be preferred in specific areas to maintain a cohesive architectural style and preserve historical or cultural heritage. What would Manhattan be without its towers?

- Land-Use & Zoning: Building types are intimately connected to land use zones within a city. Different areas are designated for residential, commercial, industrial, recreational, and institutional purposes, each of which is tied to certain building types. For example, high-rise buildings with mixed-use spaces may be used for the central business district, while single-family homes may be used for suburban areas.

- Density: The type and distribution of buildings influence population density—density being defined as the number of people per unit of land. As a quick reminder: Density may or may not relate to specific building types. It depends. But, recognizing this follow as an oversimplification, “High-density” buildings like apartments and condominiums are commonly found in city centres, promoted as being more efficient in terms of land use and reducing urban sprawl.

- Infrastructure Planning: Building types influence the demand for infrastructure and public services. For example, the construction of large office complexes may necessitate improvements in transportation networks and utilities. Residential areas, on the other hand, may require schools, parks, and healthcare services.

- Environmental Considerations: Different building types vary in environmental impacts. “Sustainable” urban planning, for example, may prioritize energy-efficient building types that incorporate specific configurations and open spaces towards using passive energy systems.

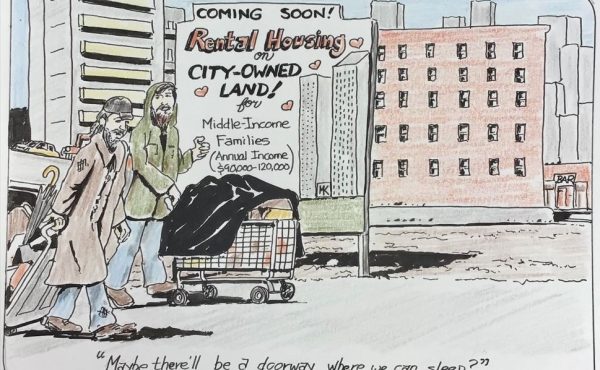

- Social & Economic Inclusivity: Building types can and do influence housing affordability and accessibility to amenities and services. Housing types are intimately tied to specific social demographics. Similarly, construction methods associated with building types affect cost. So, neighbourhoods that include affordable, diverse house types can foster social inclusivity and resilience as well as promote economic diversity within a community.

- Pedestrian-Friendly Design & Active Street Life: Specific building types that focus on street level use and experience can play a significant role in encouraging active street life. Also particularly relevant to the latter is the configuration and dimensions of lots.

- Future Growth & Adaptability: Building types that easily adapted for reuse and flexibility can help future-proof urban areas and make them more resilience through accommodating changing needs and avoiding obsolescence. The distinction between formal and use-types is particularly important in relation to flexibility and adaptability . Again, we’ll cover this in another piece.

As we can see, building types are essential to urban planning and design, influencing everything from spatial organization and affordability to other social, economic, and environmental factors. As such, the careful consideration and understanding of building types within a comprehensive urban planning strategy is critical to creating sustainable, attractive, and resilient cities.

In summary:

- Building types are essential to urban planning and design, influencing everything from spatial organization and affordability to other social, economic, and environmental factors.

- Building types are often confused with density and Transit-Oriented Development.

- Typological studies are simply classification systems meant to establish a system of analysis that breaks the city down into fundamental components evident in all settlements, regardless of culture, location, or history.

- Building types are abstract and have a rich and extensive history.

- Ordinary and outstanding buildings are all included within the building type label.

- Architectural types have ancient origins, with the earliest system differentiating “house” and “non-house.”

- The form of the building and its use are often fused together, causing confusion.

- Both “house” and “non-house” building types have expanded and diversified over time.

- Building types emerge and evolve in response to a highly complex set of social, cultural, environmental and economic conditions. Only the broader socio-cultural collective can invent and adapt building types to their specific set of needs over time. As such, individuals and organizations having very limited control in how they are born or develop.

- Building types can only be manipulated by making changes to the conditions from which they arise, not the building type itself.

- Given that society-at-large invents and adapts building types based on the complex variables that change over time, they are inherently unpredictable.

- Based on the above, the “best” building type solutions are not necessarily those “chosen” by society-at-large and the longevity of “newest” building types is not guaranteed. The newest types are the most unpredictable since they have yet to be tested over time.

- Certain building types become obsolete more quickly that others—especially those that are inflexibly tied to specific uses and functions. types can also be regulated out of existence through policies.

- There are building types that have stood the test of time—evolving with urban culture for hundreds and thousands of years until the present. These types deserves our attention.

- There are many aspects of the contemporary city that building types are connected to including: the architectural character & aesthetics of an area, land-use & zoning regulations, population density, infrastructure planning, environmental considerations, social & economic inclusivity, pedestrian-friendly design & active street life as well as the future growth & adaptability of communities.

Some Useful Resources:

- The Evolution of Urban Form: Typology for Planners and Architects by Brenda Case Scheer

- A History of Building Types by Nikolaus Pevsner

- The Writing on the Walls: Architectural Theory in the Late Enlightenment by Anthony Vidler

- UBC ElementsLab – an excellent Vancouver-based resource focusing on a typological approach to planning.

***

Other pieces in the S101S:

- S101 Series: Introduction and Call

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Why is it so Confusing?

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Net vs Gross Density•

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: FSR, Building Setbacks and Height Regulations

- S101S : Understanding Shadow Studies: Why They Matter –

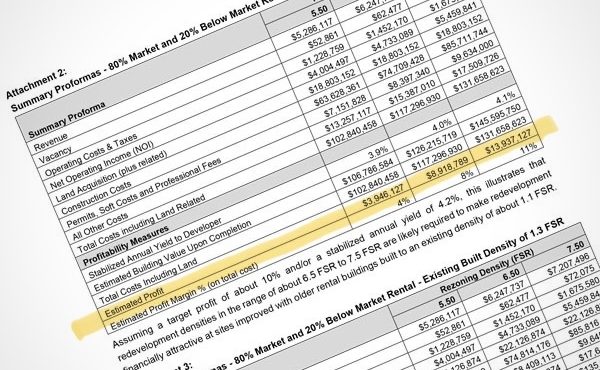

- S101S: What’s a Development Pro Forma—And Why Should you Care?

- S101S: Defining Public Space: The Basics

- S101S: Understanding Affordable Housing: The Trickle-Down Theory of Housing – Myths and Realities

- S101S: Describing Building Types: Why They Matter

- S101S: Describing Building Types: Formal and Use-Types

- S101S: Explaining Transit-Oriented Development: Benefits and Drawbacks

*

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.