What are formal building types and use-types, and why is this differentiation important to planning?

With a broad background on building types and it’s relevance to urban planning behind us, we’re ready to focus our attention on understanding two broad categories of building types—formal and use-types—and discuss why these matter.

First, let’s do a very quick recap of relevant details. Architectural building types have a rich history focusing on the classification of buildings. Typological studies establish a system of analysis that breaks the city down into fundamental components evident in all settlements, regardless of culture, location, or history. Building types are abstract, emerging and evolving in response to an extremely complex set of social, cultural, environmental and economic conditions. Only the broader socio-cultural collective can invent and adapt building types to their specific needs over time—individuals and organizations have very limited control over them. As such, their development and evolution are inherently unpredictable. However, building types can be manipulated, but only by making changes to the conditions from which they arise, not the building type itself.

It is believed that ancient civilizations simply differentiated “house” and “non-house” building types. Arguably, this is where our confusion between form and use began since the form of the house and its use were fused together under a single label. This is where we will pick up the story.

So….what is a “formal” building type?

“Formal” building type refers to the classification of buildings based on their physical form. So, it focuses on the visual and structural characteristics that certain buildings share across time, space, and culture. Physical characteristics include but are not limited to, circulation and interior layout, entry conditions, site and lot conditions, scale, and shape.

Defining a specific building type, however, is where things get a little slippery since every repetitive building has something different than the next. This being the case, Brenda Case Scheer stated it best in The Evolution of Urban Form: Typology for Planners and Architects—required reading for everybody in the field, to my mind—when she said:”Each individual building of a given type is an exemplar of that type, a variation that contains all the elements of the abstract term but may also look quite different from any other example.”

This is to say that there is no universal or standard classification of specific building types. Each can and often does vary relative to the next to some degree and the degrees of difference may warrant the development of a new type, or simply be categorized as a minor variation within a given type. At this level, it’s more art than science.

There are many examples of formal building types. On the residential side, these include the San Francisco row house and Singapore’s Chinese Shophouse. However, a local example would serve us well. The Vancouver Special has standard physical formal attributes: it is two stories with the first level at grade (no basement). The second level is the “main” level leaving an “unfinished” ground level available for a secondary suite alongside the mechanical room. The upper “main” level, on the other hand, is a fully functioning dwelling with 3 bedrooms: the layout has the public spaces (living, kitchen, dining) on one side of the house with the private spaces (bedrooms and bathroom) on the other, divided by a corridor.

A shallow balcony fronting the street—accessed by large sliding glass doors—extends along the entire or partial width of the house on the second level. The Specials are known for their shallow-pitched roofs. The simple structures are often finished in stucco, with come having brick for the street-facing facade.

In terms of site conditions, the building dimensions maximized the allowable regulations of the time with a common depth of +45ft. and the width of +26 ft as well as a covered carport at the rear. The Vancouver Specials are freestanding houses with standard rear and front yard depths.

As with other building types, Vancouver Special’s have all sorts of variations that have transformed certain aspects over time —from interior layouts to building finishes. Some of these changes may warrant the creation of a new type depending on how different they are from the “original”. But again, there is not a universal definition of the “Vancouver Special” so this becomes a game of nuance.

So, given the vagueness, why bother classifying formal building types at all?

Well, the key here is that formal building type classifications free themselves from the “use” of a building: the critical distinction between formal versus use-types. Where formal studies focus on the physical attributes, use-type classifies buildings based on their functional purpose and the activities that occur within them. This includes but is not limited to buildings like “libraries”, or “recreation centres”, “shopping centres,” “hospitals,”“theatres,” or “courthouse”. These fall under larger use categories such as “commercial,” “institutional” or “recreational” to name a few. Within residential uses, one can have many use-types ranging from “single-family” to “apartment”.

Although there is certainly a relationship between the form of a building and the activities within, its physical form cannot be presumed from its function. So with use-type, there is no explicit indication of the formal or physical character of the building. This makes it easier to innovate and experiment with them, specifically for those who design buildings.

This understanding allows us to clarify the strengths and weaknesses of each approach. In focusing on the physical attributes, formal building type analyses separate themselves from specific functions associated with buildings, allowing folks to understand how the physical characteristics of a buildings perform over time. History is filled with buildings that have transformed use within the same physical structure. Freestanding houses have changed from residential to commercial and office uses, for example, while ancient theatres have been changed to housing. Such transformations speak to the inherent capacity of certain physical forms and spaces to adapt to different conditions. Very useful information for those planning cities, don’t you think?

This comes at the expense, however, of the openness of defining a building by use. Despite the slipperiness of defining specific formal building types, they are still much more specific than use. Think of how many different “single family house” forms there are: are we talking about a Vancouver Special? A New England Saltbox? A shotgun house? A Levittown house? Simply put: the ambiguity of use-type allows folks to understand and use the general activities within a given building types, without begin bogged down by a strict set of specific physical characteristics.

Now, let’s address the issue we began with: the early history of building types caused a Big Confusion that continues today…one that fuses form and use under single labels. This is an issue that prevents the meaningful discussion about cities everywhere, as people say one thing and mean something else. It’s common, for example, for many to vilify “single-family houses” currently as a broad use-type, despite the fact that there are many specific (formal) building types that have shown the capacity to adapt to higher densities and different uses over time. It’s not an all-or-nothing issue.

The Vancouver Special will serve us well here again since it can effectively double and sometime triple the density of the stereotypical “single-family house” use-type under which it is categorized. This capacity is due to its physical characteristics. The fact that it has the built-in capacity to separate activities by floor level means that it can adapt to very different uses. The bottom floor can be be changed to commercial uses, for example, with the upper level remaining residential. Or vice versa. As such, although it looks very different, it shares the attributes with much older (formal) building types like the ancient shophouse—one of the most robust, adaptable formal building types created by humans to-date.

The above example serves as a good entry into some final insights. Not only is building type—as a general category—confused with other complex issues like density or specific development approaches like Transit-Oriented Development, but even within the discussion of building types, it is often unclear if and when people are talking about formal or use-types. Like with so many planning related issues, clarity is important.

Although conversations about use-type are excellent for typological innovation, within the context of planning and designing cities over time, discussions should focus on formal building-type and how the physical attributes of specific buildings have performed over time. Not only can these attributes translate readily into targeted regulations and policies, but such an approach will also prevent the common trap of worshipping the newest, novel building types. Formal building types have a lineage of thousands of years, learning from them is simply common sense.

Moreover, many common planning goals can be achieved through understanding formal building types. Many municipalities speak about creating resilient cities or neighbourhoods, for example, and an appreciation of flexible, adaptable building forms and systems is necessary to meet that goal. Several types that can serve this end. Are there building types that are more conducive to making community through increasing social collisions? There sure are. Again, all it takes it understanding the connection between building forms and different outcomes.

Ironically, few municipalities around the world have any information on the formal building types within their boundaries, let alone meaningful global examples. Instead, use is often the basis of urban planning discussion and regulations, undermining meaningful discussions about the physical environment and its transformation over time. Even at the large scale of planning, breaking down the city by land use is the most common—categorizing areas by the activities that take place within. Although informative, this leaves out an understanding the physical implications and nature of a place created through these regulations. A “residential” area depicted on a land use map says nothing about the physical character of a place. Is it bungalows? Vancouver Specials? Who knows. Similarly, “commercial” areas can mean anything from malls to corner stores. At the urban scale, it is useful to set aside the use of buildings as a means of discovering more basic, fundamental physical patterns.

Local schools of architecture and those that study urban morphology (an important topic we’ll cover in future pieces) can help with the typological information deficit of municipalities, however. Typological studies on formal building types and use-types happen frequently within their domains and one can see how collaborations can be fostered between these different institutions. Unfortunately, most planning schools do not engage typological studies in any meaningful way, less so formal building types. This explains the default use-based approach of the urban planning discipline.

With our foundation on building types now set, future pieces of the S101S: Describing Building Types series will focus on understanding specific formal building types relevant to the contemporary city. Until then….

In summary:

- “Formal” building type refers to the classification of buildings based on their physical form. It focuses on the visual and structural characteristics that certain buildings share, including, but not limited to, circulation and interior layout, entry conditions, site and lot conditions, scale, and shape. Examples of residential formal building types include the San Francisco row house, Singapore’s Chinese Shophouse and the Vancouver Special.

- There is not a universal definition of specific building types so deciding what constitutes a different building type or variation within a building types is more art than science.

- Use-type classifies buildings based on their function, use or the activities that occur within them, not the physical characteristics of formal building types. This includes but is not limited to buildings like “libraries”, or “recreation centres”, “shopping centres,” “hospitals,”“theatres,” or “courthouse.”

- Both formal building type and use-type classifications have drawbacks and benefits.

- In divorcing the physical aspects of a building from its use, formal building type analyses serve well for gaining an understanding of how buildings perform over time. This is excellent for planning cities over the long-term.

- Use-type analyses facilitate innovation within a building type since folks are not constrained by the physical characteristics of a building type but still have a clear understanding of the uses and activities housed within it.

- Speaking to building types that fuse form and use under single labels causes confusion. For example, there are many formal building types under the “single-family houses” use label.

- Within the context of planning and designing cities over time, discussions should focus on formal building types and how the physical attributes of specific buildings have performed over time: attributes that can then translate readily into specific regulations and policies.

- Unfortunately, use-types are often the basis of urban planning discussion and regulations, undermining meaningful discussions about creating a resilient built environment and its transformation over time.

- Few municipalities around the world have any information on the building types within their boundaries, let alone meaningful global examples. Local schools of architecture and urban morphology can help with this since they analyze formal building types and use-types frequently.

Some Useful Resources:

- The Evolution of Urban Form: Typology for Planners and Architects by Brenda Case Scheer.

- Anatomy of Sprawl by Brenda Case Scheer – an excellent, accessible article demonstrating the strength of a morphological approach to urban planning, including the role of building types across time.

- Built for Change: Neighborhood Architecture in San Francisco by Anne Verne Moudon – a comprehensive study of the San Francisco row house.

- Brussels Housing: Atlas of Residential Building Types by Gérald Lebent and Alessandro Porotto – a recently published, comprehensive book on house types in Brussels. “Atlases” on building types are rare and this is the most recent to be released, that I know of.

- Atlas of the Dutch Urban Block by Susanne Komossa, Han Meyer, Max Risselada, Sabien Thomas and Nynke Jutten – now out of print but an excellent resource for building and block types in the Netherlands, including Amsterdam.

- Chinatown: Historic District by the Singapore Urban Redevelopment Authority – one of the few formal type studies done by a government agencies looking at their Chinese shophouse. Unfortunately, one can only pick it up.

- Suburban Space: The Fabric of Dwelling by Renee Chow.

- 6000 Years for Housing by Norbert Schouenauer.

- Interpreting basic buildings by Gianfranco Caniggia and G. Luigi Maffei.

- A History of Building Types by Nikolaus Pevsner.

- The Writing on the Walls: Architectural Theory in the Late Enlightenment by Anthony Vidler.

- UBC ElementsLab – Typological Approach to Future Urban Form Scenarios – an excellent Vancouver-based resource focusing on a typological approach to planning. This specific piece describes a pilot project using an iterative, rules-based typological approach to Vancouver’s urban form.

Related pieces in the S101S:

- S101S: Describing Building Types: Why They Matter

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Why is it so Confusing?

- S101S: Explaining Transit-Oriented Development: Benefits and Drawbacks

**

All pieces in the S101S:

- S101 Series: Introduction and Call

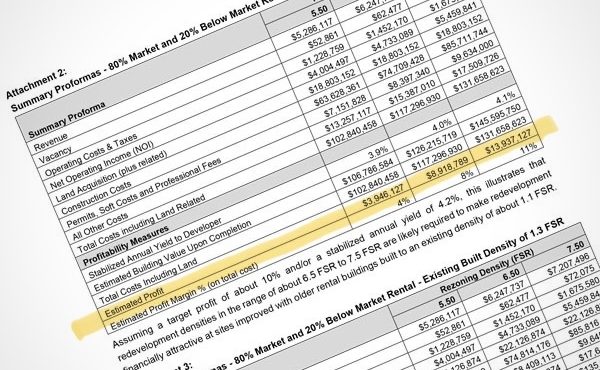

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Why is it so Confusing?

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Net vs Gross Density•

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: FSR, Building Setbacks and Height Regulations

- S101S : Understanding Shadow Studies: Why They Matter –

- S101S: What’s a Development Pro Forma—And Why Should you Care?

- S101S: Defining Public Space: The Basics

- S101S: Understanding Affordable Housing: The Trickle-Down Theory of Housing – Myths and Realities

- S101S: Describing Building Types: Why They Matter

- S101S: Describing Building Types: Formal and Use-Types

- S101S: Explaining Transit-Oriented Development: Benefits and Drawbacks

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.