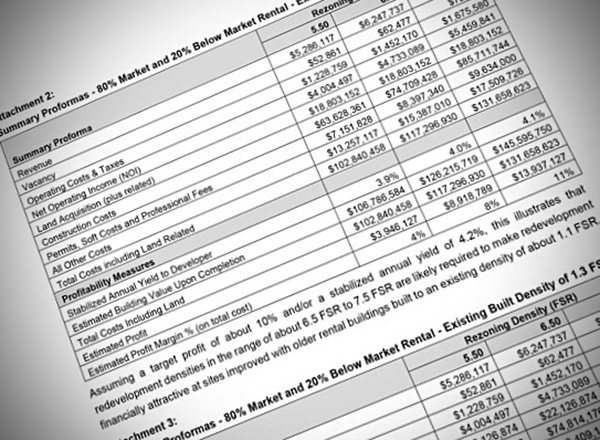

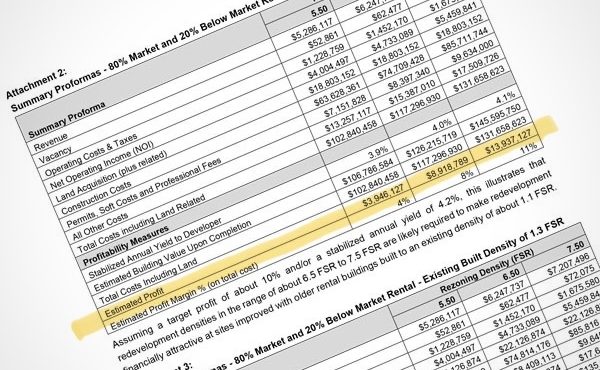

A development pro forma is one of the most important (yet often overlooked) tools in real estate and urban planning. Think of it as the financial blueprint for a development project—it lays out the estimated costs, revenues, and potential profits before a single brick is laid. Developers, investors, and planners rely on pro formas to decide whether a project makes financial sense. If the numbers don’t add up, the project doesn’t happen.

But here’s the thing: pro formas don’t just determine whether a building gets built. They shape what kind of development happens—who it benefits, who gets left out, and whether a project serves the broader community or maximizes profit. If you’ve ever wondered why many new developments lean toward wealthier clientele instead of affordable housing, the pro forma is a big part of the answer.

Even though they’re so influential, pro formas can be dense and full of jargon, making them hard to understand for anyone outside the real estate world. And because they often prioritize financial returns over social good, it’s important to know how they work—especially if you care about making cities more inclusive, sustainable, and livable.

So let’s break it down.

Although pro formas vary in detail from project to project and across different contexts, a strong development pro forma typically includes six main components:

- Land and Acquisition Costs

- How much does the land cost? This includes the sale price as well as legal fees, taxes, and any costs tied to rezoning or environmental cleanup. Land is usually one of the biggest expenses, and high land costs often push developers toward luxury housing to make the numbers work.

- Hard Costs (Construction Costs)

- This is the actual cost of building the project—labor, materials, permits, contractor fees. If these costs rise (say, due to supply chain disruptions), the entire financial model can shift.

- Soft Costs (The “Hidden” Expenses)

- These include architectural and engineering fees, marketing costs, legal expenses, and project management. Soft costs don’t always get as much attention as hard costs, but they can add up fast.

- Operating Income and Expenses

- How much money will the project make once it’s up and running? This section forecasts rental income, sales revenue, and ongoing expenses like maintenance, property management, and insurance. If a development isn’t expected to generate enough income to cover its costs, it’s a no-go.

- Financing and Loan Costs

- Most projects are funded with a mix of loans and investor capital. This section lays out interest rates, loan terms, and repayment schedules. Developers want to secure the best financing terms to keep their costs low and profits high.

- Return on Investment (ROI) and Profitability

- At the end of the day, developers and investors want to know: Is this project worth it? Metrics like Net Operating Income (NOI) and Internal Rate of Return (IRR) help determine whether a project is financially viable. If the projected profits aren’t high enough, developers may tweak the pro forma—often by cutting affordable units, shrinking public spaces, or raising rents.

On paper, a pro forma is just a financial model. But in reality, the way it’s structured—and what it includes and omits—has huge implications for cities.

A lot of pro formas are built with a profit-first mindset. That’s why developers often push for high-end projects—luxury condos, premium office space, etc. Simply put: they are the most profitable. Meanwhile, projects that prioritize other aspects—such as affordable housing, public amenities, social equity, or environmental sustainability—can get sidelined because they don’t deliver the same short-term financial returns.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. Pro formas aren’t set in stone. The numbers in them depend on many assumptions—about land costs, expected profits, financing, public subsidies, and many more. Cities that take an active role in shaping pro formas (through incentives, zoning policies, or community benefits agreements) can influence what gets built and who benefits.

So, although a development pro forma might seem like just another spreadsheet, it’s actually a powerful decision-making tool that shapes neighbourhoods, housing markets, and public spaces, and so much more. Understanding how it works helps us ask smarter questions about development, such as:

- Why does this project include (or exclude) specific types of housing?

- How are financing costs influencing what gets built?

- What assumptions are driving the decisions made and their conclusions?

- Who benefits financially from this development—and who doesn’t?

Pro formas aren’t going away, but they don’t have to be used solely to maximize investor returns. With more transparency and smarter policies, they can be used to create developments that serve both financial, community, and environmental interests.

In Summary

- A development pro forma is a financial tool used to assess whether a real estate project is viable.

- It includes six key components:

- Land and acquisition costs – The price of land and related expenses.

- Hard costs – Construction expenses like labor and materials.

- Soft costs – Fees for architects, engineers, legal work, and marketing.

- Operating income and expenses – Projected revenue and maintenance costs.

- Financing and loan costs – The debt and equity used to fund the project.

- Profitability metrics – Key financial indicators like ROI and IRR.

- Many pro formas prioritize profit maximization, which often leads to high-end developments over affordable housing or public amenities.

- The assumptions in a pro forma determine what gets built and who benefits. They should be stated transparently for assessment and debate.

- Cities and communities can influence pro formas through policies, incentives, and negotiations.

Some Useful Resources:

- Infrastructure Institute – Social Purpose Real Estate (SPRE) Resources: Offers a repository of resources for social purpose real estate projects, including toolkits and templates that can assist in preparing pro formas tailored to non-profit and community-focused developments.

- Urban Land Institute Learning: Offers a variety of courses including some on best practices for balancing financial and social goals in development.

- Richard Peiser – Professional Real Estate Development: A detailed look at the financial and managerial side of real estate development.

- Christopher Leinberger – The Option of Urbanism: Examines how financial models shape the kinds of places we build.

***

Other pieces in the S101S:

- S101 Series: Introduction and Call

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Why is it so Confusing?

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Net vs Gross Density•

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: FSR, Building Setbacks and Height Regulations

- S101S : Understanding Shadow Studies: Why They Matter –

- S101S: What’s a Development Pro Forma—And Why Should you Care?

- S101S: Defining Public Space: The Basics

- S101S: Understanding Affordable Housing: The Trickle-Down Theory of Housing – Myths and Realities

- S101S: Describing Building Types: Why They Matter

- S101S: Describing Building Types: Formal and Use-Types

- S101S: Explaining Transit-Oriented Development: Benefits and Drawbacks

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.