Although the recent pandemic has brought to light many important issues, none has been more pervasive than social distancing. Embedded in this discussion is that of a foreseeable future within which social distancing is the norm. But few have really delved deeply into the implications of such a future scenario and its impact on the city. What does this mean for the physical fabric of the built environment? More importantly, can our settlements even adapt to such a future and to what degree?

Insofar that the material world is intimately related to—in fact, a direct extension of—our bodies, these questions are extremely relevant. Bombarded every day with new buildings, constant streams of demolitions and renovations, it’s easy to think that settlements are ultimately malleable: that a simple expansion of distance between people is relatively straightforward. Unfortunately, nothing could be further from the truth.

Given that settlements are constructed from physical, substantial material, this series will explore something simple and concrete—a physical dimension. Or perhaps more accurately a very narrow range of physical dimensions that can roughly be captured by the single 3ft/1m measure. It is a measure rooted in the human body…one so pervasive and fundamental to the way we inhabit space that it goes effectively unnoticed. Consequently, it is also the dimension indirectly implicated by the 6ft/2m social distancing directives of the pandemic.

And although much is being said about the ability to carry on life in a “somewhat normal” way within the Six-Foot City, a brief foray into how prevalent this 3ft (1m) dimension is—how truly embedded it is within the built fabric of our settlements—will serve to show that there is nothing “normal” about the Six-Foot City. The Six-Foot City is an altogether different organism. An alien environment. Or at the very least, a radical reconstruction of the settlements we know. In no uncertain terms, the Six-Foot City is fictional. It can never—will never—be built.

Before delving into the details, however, it’s worth understanding that physical space is a medium of communication. This may seem abstract, but it isn’t. It’s a language we use every day. This perhaps finds its clearest expression in our sense of “personal space”. Despite the fact that few of us can put a distinct measurement on it and that there are cultural variations, all humans around the world share the ability to sense when a stranger has ‘invaded’ their ‘personal space’.

This is context-specific, of course, since one’s personal space expands and contracts depending on the person with which you are interacting and the spaces you are in. While a loved one is allowed within the range of touch and smell, others might not be. On public transit, there’s a general social consensus that one’s typical personal space limit must shrink to allow strangers access to the bus or train during busy hours. This spatial language is species-specific. Imagine what a different world we would have if humans walked over each other like ants?

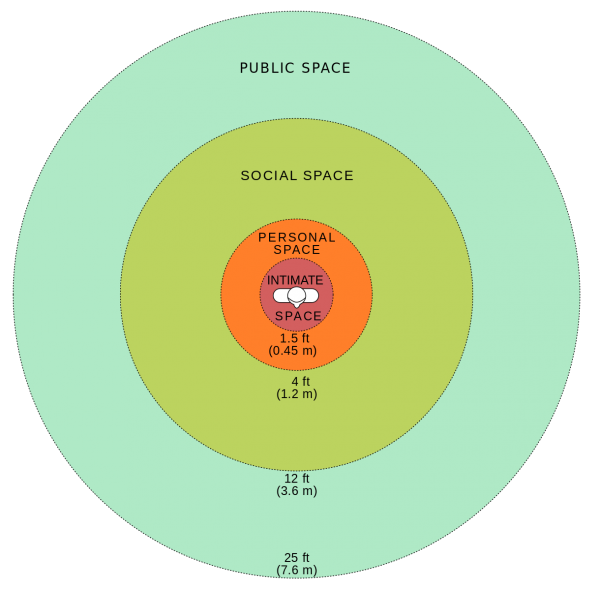

Consequently, many have studied, analysed, and attempted to measure the layers of spatial boundaries we all share. This served as the foundation for a variety of disciplines including anthropometrics, ergonomics and proxemics. And within the latter, cultural anthropologist Edward T. Hall stands out as one of the earliest and most influential. He was among the first to clearly categorize, describe and popularize the interpersonal distances of humans: dividing them into four distinct zones. Radiating out from the body, he defined the intimate space (ranging approx. from 1”-18” / 1cm-50cm), personal space (1.5ft-4ft / 0.5m-1.2m), social space (4ft-12ft / 1.2m-3.7m), and public space (+12ft / +3.7m).

It’s important to note, however, that Hall’s spatial zones existed prior to any study. He, and those that subsequently branched off his tree, simply attempted to categorize and organize real-world phenomena. The spatial measures of social interactions were already embedded in the built world long before they were conceptually organized within a framework. This is very clear across the globe, and is evident in all aspects of the built environment, from the 3ft x 6ft (0.9m x 1.8m) tatami mat dimensions of the traditional Japanese house to the 4.5ft-6.5ft (1.4m-2m) private cul-de-sac streets of centuries-old Arab-Islamic settlements.

Although Hall’s initial work and conclusions had clear cultural biases (as do all endeavours that attempt to make broad conclusions related to the human body) and distances vary from individual to individual, for our purposes, it serves as a satisfactory baseline for understanding specific measurement and their relationship to the human body and comfort. Within the context of the built landscape, this understanding will give us a dimensional frame of reference, allowing us to see how certain dimensions have been adopted and codified for much of the everyday built environment, and how these are affected by the 6ft (2m) social distancing directives.

As mentioned earlier, bodily measures and settlements have been intertwined from the start. Of these dimensions, Hall’s ‘personal space’ distances of 1.5ft-4ft (0.5m-1.2m) and the lower limited of his social space (4ft-12ft / 1.2m-3.7m) are arguably the most evident in our everyday environments. It is the comfortable zone that most social interactions take place within. Simply put, humans have mainly built, and dwelled, within Three-Foot Cities.

Insofar that globalization has served to distribute and homogenize various aspects of the built world, it did so through adopting dimensional foundations, specifically in the form of international building codes and standards that outline minimum and maximum spatial dimensions for particular activities. These, in turn, also evolved from the Three-Foot roots of its predecessors. Consequently, the incredible speed that humans have created built settlements of all types over the past decades has ultimately served to propagate constructed environments based on common body-centred measures.

So herein lies the critical question: what are the impacts of doubling the current personal space radius from 3ft (1m) to 6ft (2m) across an entire society?*

This series will explore this question, focusing on three everyday spaces that map very crudely onto living, working, and moving around the city—more specifically, the corridor, the classroom, and public transit. Each will include a very brief history of the origins of each space as it relates to body-based dimensions and social relationships. This will be followed by some speculation within the context of a fictional Six-Foot City.

To be clear, this is not about criticizing or undermining current efforts to integrate social distancing measures. Instead, it is intended to give readers a greater appreciation of our everyday environment and the intricate, complex, and invisible role the human body plays within it: showing how seemingly harmless changes to our body-centred system has ripple effects across all aspects of our daily lives. We’ll begin with one of the most common spaces in the modern city—the corridor.

***

*For all the math geeks out there, this doubling would equate to roughly a four-fold increase in area per person.

**

You can read the other pieces in the Six-Foot City series here:

*

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places.