The lowly corridor falls well short of being adored by most people. Within our contemporary cultural imagination, its association with darkness and evil has few equivalents. Its image as a miserable, narrow, lonely, and monotonous space is only eclipsed by its prevalence in the modern world.

The conceived nature of the space notwithstanding, the story of the corridor is quite interesting. The idea of the corridor is believed to have its earliest roots in China between 12th-7th BCE, where it was associated with a space enclosed by a roof and wall along one side. In Europe, it is etymologically linked to the 6TH century Latin “curro” meaning to run. During the 14th century Italy, the “Corridore” aptly referred to the space for running on top of—or next to—the fortified city walls.

The corridor’s connection to movement and flow was firmly established by the 18th century, where it found its fullest expression in the modern cellular institutional architecture of asylums, prisons, and hospitals, as well as the rapidly evolving social housing projects.

The ‘open plan’ movement of the late 1800s started the corridor’s rapid demise, as it was deemed antithetical to ideals of open vistas and transparency held so dear. This demotion left it as an architectural afterthought, retreating to the deep underbelly of contemporary building design—an accessory for safe exiting, effectively determined by building code minimums and outfitted in an increasing number of safety signs, lights and sensors.

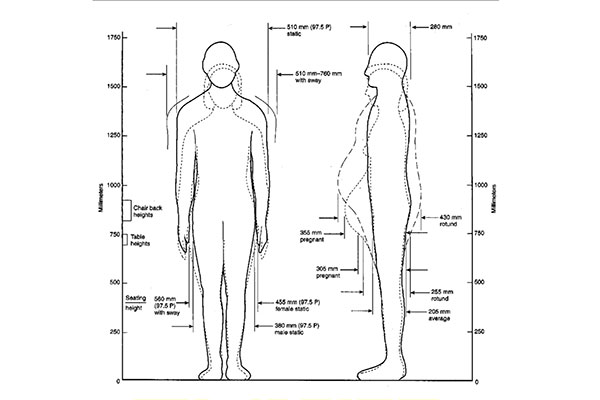

But what lies at the root of standardized exit corridors dimensions? The human body.

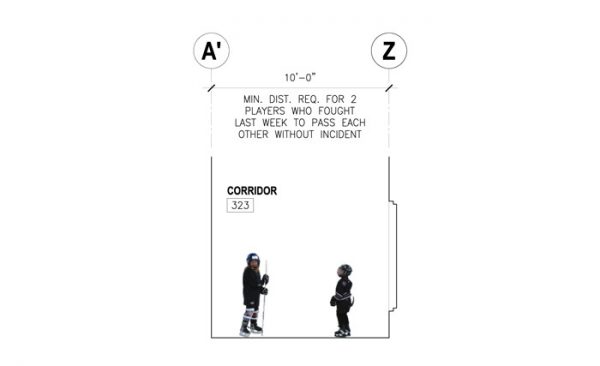

Fire safety is the dominant driver of corridor minimums, with the International Building Code requiring a minimum width of 44-inches (1.12m). This is based on a standard body, 22-inches (0.56 m) wide: a dimension that, according to the SFPE Handbook of Fire Protection Engineering, is intended to support queues of two people moving together or in opposite directions (think, firefighters or responders moving in the opposite direction of those leaving). According to the book, the measurement was developed in 1914 and was based on “soldiers standing still in a line.”

As a neglected but critically important safety space, the increasing size of buildings over the past decades based on international codes has only led to the drastic proliferation of building corridors. Abandoned by designers, the economically-driven nature of development has meant that the vast majority of these spaces remain strictly at their minimum. The result is an architectural landscape overrun by 44-inch (1.12m) passageways…and by extension, the 44-inch emergency stairways that many use on a daily basis.**

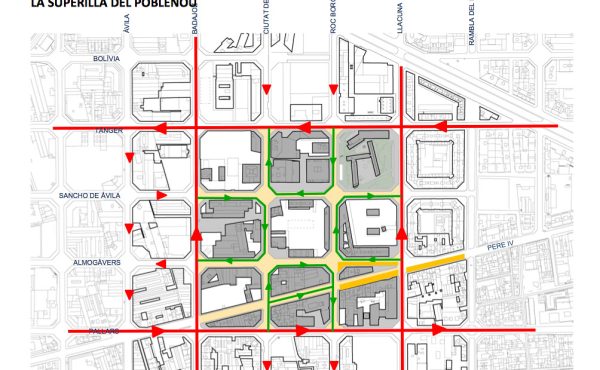

This stands in stark contrast to the Six-Foot City: an environment that requires that these pervasive corridors effectively double their width to ensure appropriate social-distance requirements. The sheer scale of such an undertaking—the transformation of thousands of square feet of the existing built area—would make such an initiative virtually impossible, even if it was desired.

But this speaks nothing to speculation: what are the implications of doubling the minimums for corridor spaces?

Amidst the increasingly complex interplay between regulations, design, and development economics already governing the creation of architecture, even a small adjustment to this equation would have systemic repercussions that would be difficult to predict. That said, within the context of the mid- to large-scale projects commonly built, even a crude forecast can envision a scenario where doubling the width allocated to the ubiquitous corridors and safety circulation would lead to the vast growth of floor area requirements.

With increased construction costs given over to ‘pragmatic’ spatial infrastructure (versus saleable space such as living units), a call for more floor space allowances could easily ensue, as developers seek to retrieve the money put towards these ‘support’ areas. Conversely, certain municipalities might choose to exclude corridor and stair widths from the floor area calculations (as was done for Olympic Village in Vancouver) and this could lead to more socially productive circulation spaces. Something very beneficial for all!

The ultimate effect of the latter would be felt at the scale of the city in the form of radically increased architectural bulk—much taller, wider and/or deeper buildings—enclosing streets and public spaces across the built environment. Attempting to maintain existing size and area regulations would mean much smaller living spaces, particularly within denser urban contexts…as if they could get any smaller!?!? Regardless, the economic impacts of doubling of corridor width would spur radical change in new buildings.

Strict adherence to 6ft social distance protocols would mean that in the countless existing structures designed around minimum circulation standards, people would have to queue up for virtually all circulation routes, including elevators* and fire stairs. This architecturally choreographed musical-chairs would require an interestingly intricate coordination system between those circulating around buildings to avoid close contact and long wait times to get from one space to another. Imagine having to schedule a 15-minute wait at the front door of your apartment to just get out of the building every morning?

We take for granted how much of the everyday built environment is based on the dimensions of the human body. Simple minimum dimensions for corridors may seem benign, but when applied to hundreds of buildings across hundreds of cities they have an enormous impact on how the city works and how we behave to boot.

As you can see, the Six-Foot City is very different from any settlement humans have created. As one of the basic spatial units of contemporary architecture rooted in the body, the corridor offers a small but meaningful glimpse into the tremendous scaling effects of seemingly small changes to the body-centred ordering systems we’ve adopted over thousands of years.

And while the corridor offers an extreme example, the scale of changes required towards six-foot distancing, the impacts of transforming body measurement norms across less common spaces is also far-reaching—some beyond built enclosures to the inherent functioning of our economy. The classroom is one such example…one that we will deal within the next piece.

***

*Typical elevators measure between 5.7’x 4.25’ (1.7m x 1.3m) to 5.7’x 7.9’ (1.7m x 2.4m), enough for one- and two-people per trip, respectively.

** Naturally, there are many alternatives to using minimum standard corridor widths. Here is a fun one:

**

You can read the other pieces in the Six-Foot City series here:

*

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements across Scale and Culture. He is also an educator, independent researcher and designer with personal and professional interests in the urban landscapes. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places. You can see more of his artwork on his Visual Thoughts Tumblr and follow him on his instagram account: @e_vill1.