That the pandemic has had a disastrous effect on local and global economies is blatantly clear. But we take for granted that the contemporary economic engine—buoyed by peoples’ ability to work— is fundamentally supported by the education system. That is, the standard adult ‘workday’ is largely made possible because children go to school, freeing parents and caregivers of childcare responsibilities.

The lockdowns, that have seen parents and children sharing spaces for work and school, have served to amplify this critical work-school relationship and it’s evident that any attempts to get people back to work must be done alongside getting children back into schools. Given the new requirements for physical distancing, it’s imperative to take a closer look at the history of the school building and the classroom to understand the feasibility of this task.

Like all building types, schools are created from a few spatial building blocks. At their most basic, contemporary schools are simply collections of corridors plus classrooms—the latter being the educations systems most symbolic and cellular unit.

In North America, the earliest modern schools were religious endeavours run by churches. Prior to this, wealthy children were tutored at home, while those less well-off either received no formal education or organized their own education on a case-by-case basis (i.e. through work apprenticeships, etc.). Initial attempts at public formal education in the early 19th-century found its clearest architectural expression in the one-room schoolhouse, with teachers on a platform speaking to rows of pupils.

Although school design has changed—and continues to transform—alongside evolving educational philosophies, the spatial foundations of the standard classroom in schools new and old—from K-12 through higher education—has largely remained the same: the human body.

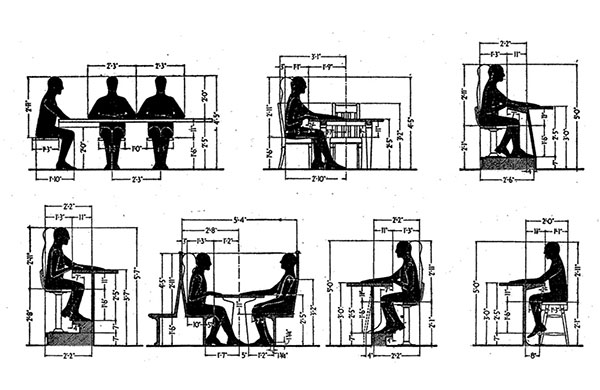

Rooted in the value of group learning, and driven by the hard economics of maximizing students per teacher per room, classrooms effectively force close contact among students. Although desk dimensions—and therefore spacing between students—varies with age and different furniture arrangements, the average recommended side-by-side distances between students lies around 24” (0.6m) with 3ft (36”/0.9m) in front and/or behind. Auditoria with fixed seating have even tighter measures.

This makes schools, at all levels, among the institutions most affected by changes to body dimensional norms, as these are intimately woven into the very fabric of the educational environment. This speaks nothing to other school-related spaces that would also require drastic reconsideration based on the latter, from schoolyards to gymnasiums, each area of which is calculated based on occupancy numbers.

In the Six-Foot City, then, standard K-12 classroom capacities would dwindle to at least one third their current use, as side-by-side distances required between each student effectively triple. This translates crudely to students being in a physical class one-third of the typical school year.

In an economy based on the standard 7.5hr workday, a radically different education-childcare system would have to be created: one that allowed K-12 students, in particular, to get the education they required in the absence of parent-caregiver oversight.

If new schools were to be built to accommodate the bodily standards of the Six-Foot City, building footprints would explode to accommodate the thousands of students currently registered within the school system. More so, if new Six-Foot City standards for corridors were also put into play. This would serve to decrease outdoor spaces. Within smaller urban sites, confined outdoors play areas would be the norm: some of which may dwindle to nothing at all.

How could smaller outdoor environments contain the high numbers of students who would still be required to maintain 6-ft (2m) distances? This might launch the widespread use of the new, expansive roof areas for play and other outdoor activities…something already found in different space-confined cities around the world.

Existing schools would need to function on a rotational basis, with one-third of the standard student group coming in every third day. How students would be educated and supported during the other two days while parent-caregivers to go to work would require the development of new societal systems, as home-based non-supervised learning would not suffice (as our current experience makes so clear).

Already, some are discussing interesting alternatives to the standard classroom-based learning system, such as the City-As-School learning-by-doing model in New York City that runs on a highly personalized mix of internships, classwork, and portfolio preparation.

Given how intertwined work and school are, a new system might also see fewer official “work days” to allow parents-caregivers to oversee children in combination with intricately developed online learning modules for remote learning. Or the creation of work environments that integrate student spaces and infrastructure for remote learning, so that parents-caregivers can bring their children to work on days off school. Perhaps getting rid of weekends? Staggering school weeks? The possibilities and combinations are endless.

One thing is for certain, however, education and the working lives of Six-Foot City citizens would be much different than our current reality. And we would have to dig deep into many questions around learning and working, not the least of which is the physiological impact of morning, afternoon, and evening learning/working?

Classrooms aren’t the only spaces that function on maximizing close contact, however. Public transit relies on it to survive. What might this look like in the Six-Foot City? This will be the focus of the next article in this series.

**

You can read the other pieces in the Six-Foot City series here:

*

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements across Scale and Culture. He is also an educator, independent researcher and designer with personal and professional interests in the urban landscapes. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places. You can see more of his artwork on his Visual Thoughts Tumblr and follow him on his instagram account: @e_vill1.