EDITOR’S NOTE: With affordable housing debates raging, misinformation is everywhere. Trickle-down housing narratives loom large in the used-and-abused language littering media—with references to Alain Bertaud’s Order Without Design being particularly popular. Unfortunately, most references to the latter under the guise of “conventional economics” are incomplete, at best. Oversimplification is rampant. It’s time to go back to foundations to get things straight…and is it with heartfelt gratitude that we at Spacing Vancouver provide the following special edition of S101S—guest edited by Alain Bertaud.

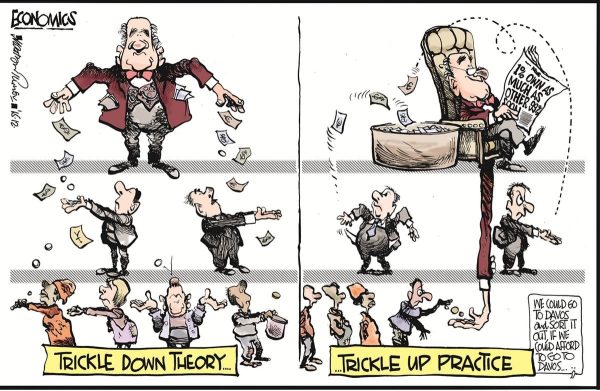

With housing challenges dominating discussions in cities around the world, it’s no surprise that solutions are often framed with catchy phrases that feel simple and intuitive. Unfortunately, some of these phrases get repeated so often that they’re mistaken for truths. The “trickle-down theory” of housing, also known as filtering, is a prime example of this—a concept thrown around in debates, often without a real understanding of its limitations. Politicians are especially guilty of this, but they’re not the only ones who treat the theory as an absolute, rather than a framework riddled with flawed assumptions.

Before diving into the nitty-gritty, let’s pause and remind ourselves what a theory is.

A theory is a way to explain how or why something works, based on evidence and reasoning. It’s not a law of nature. It’s an interpretation of observations that can help us make predictions or identify patterns. Theories are powerful tools, but they’re not absolute truths. They evolve when new evidence or perspectives emerge, and almost always work within certain conditions. Importantly, theories are shaped by the biases and viewpoints of the people who develop them. This means they’re inherently limited—they might not fully capture the complexity of real-world situations.

That brings us to the trickle-down, or filtering, theory of housing. Despite being treated like fundamental truth in some circles, it’s far from an unshakable law. It hinges on assumptions that don’t always hold up in reality.

So, what is the trickle-down theory, exactly? It’s the idea that as new, higher-end housing is built, wealthier households move into it, leaving behind older, less expensive housing for middle- and lower-income groups. On the surface, it sounds like a natural and efficient way to address housing affordability—simple, right? Well, too simple. The reality of housing markets is far messier, shaped by supply constraints, inequalities, and policies that disrupt this supposed flow.

To understand why the trickle-down theory doesn’t work as neatly as advertised, we need to unpack the assumptions it’s built on. Here are the three big ones—and why they fall apart in practice:

- Housing Supply is Elastic Across All Levels: This assumption suggests that developers can and will build enough housing at all price points to meet demand. But in reality, restrictive zoning laws, high construction costs, and regulatory barriers make it easier to focus on high-end projects, where profits are higher. This leaves lower-income households with few, if any, new options.

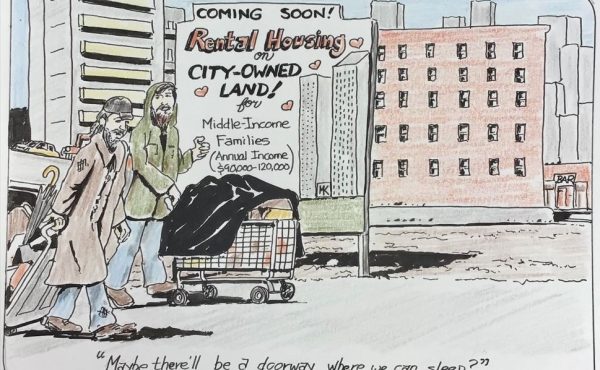

- Market Dynamics Alone Ensure Equitable Distribution: The theory assumes that as wealthier households vacate older units, these homes will naturally “filter down” to lower-income groups. But what actually happens? Older units are often renovated, repurposed, or snapped up by investors, especially in gentrifying neighborhoods. Rather than trickling down, housing tends to “trickle up,” with wealthier households outbidding poorer ones for any available stock.

- Homogeneous Housing Needs: The theory also presumes that the vacated housing stock will suit lower-income households in size, quality, and location. In practice, this rarely aligns. Housing that’s too far from jobs or services—or units that are too large and expensive to maintain—don’t solve affordability issues for those most in need.

These flawed assumptions explain why the trickle-down theory fails as a standalone solution. It reduces the complex issue of housing affordability to a simplistic, linear process that ignores structural inequities and spatial realities. Left to their own devices, market forces prioritize profits, not inclusivity, leaving the most vulnerable populations underserved. The market is a mechanism without feelings or moral values.

Alain Bertaud, in his book Order Without Design, offers a sharp yet balanced critique of this approach. He argues that while the trickle-down effect might occur in limited ways, it cannot address the full complexity of housing supply and demand. For example, in Shanghai, even large-scale construction of new housing didn’t alleviate affordability challenges for lower-income groups because the new supply wasn’t distributed in a way that matched their needs.

Bertaud also sheds light on the opposite phenomenon—the “trickle-up” effect. When supply is constrained, wealthier households outbid poorer ones for existing housing, often displacing the latter in the process. This dynamic, seen in cities with restrictive zoning and high demand, often worsens inequality. In Chennai, for instance, subsidized housing meant for lower-income groups was frequently purchased by higher-income households able to pay more. Such examples highlight how housing markets respond to economic forces, not intentions, and why simplistic models fail to deliver equitable outcomes.

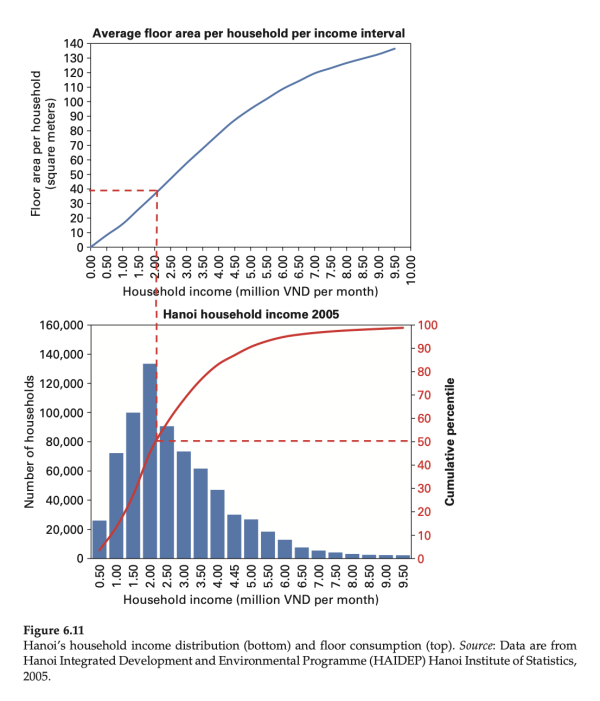

Another critical piece of the puzzle is understanding housing consumption—the type and amount of housing that different households actually occupy. This includes floor space, location and quality. Lower-income households often “consume” far less housing than socially acceptable standards dictate, whether it’s due to inadequate size, poor location, or substandard quality.

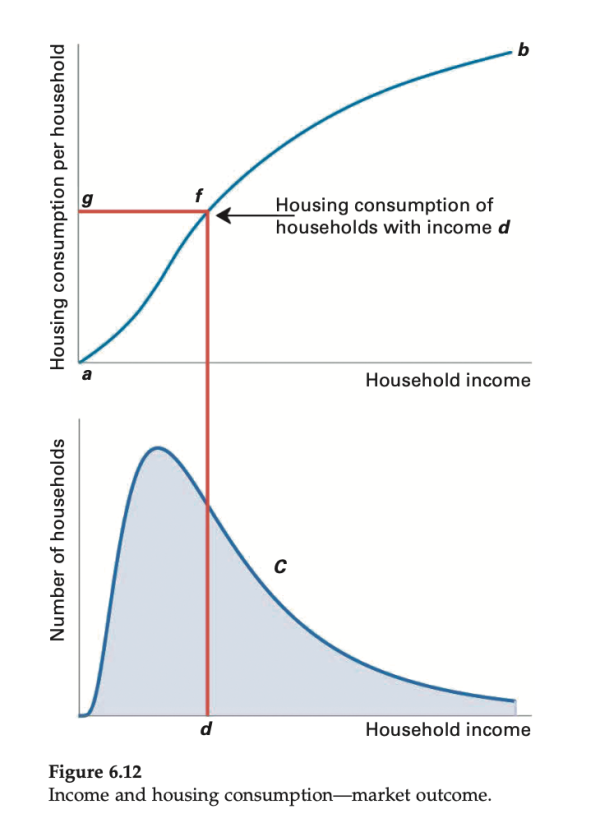

Bertaud’s method explicitly links income distribution to housing consumption (i.e. floor area requirements) and shows how it can be used as a diagnostic tool to dictate market outcomes. As seen below, this information can be connected graphically to inform policy and decision-making.

Bertaud is clear in how this method can be applied to other cities, using Hanoi, Vietnam as a case study.

The importance of housing consumption data can’t be understated and it’s worth noting that most cities don’t collect housing consumption information to the degree that Bertaud outlines. Floor area needs of different income groups, for example, are rarely gathered and local municipalities like Vancouver are no exception. This prevents governments from identifying the deficiencies necessary for supplying affordable housing and addressing them effectively. Without the full suite of information, governments can only speculate (pun intended) on how to tackle affordability.

Bertaud also addresses, direct subsidies or income supports given that they are often proposed as solutions to help low-income households bridge the affordability gap. While these can empower households to make choices that best suit their needs, their success depends on critical conditions. The institution providing subsidies must have sufficient resources to meet the demand for the entire qualifying group quickly. Otherwise, households languish on waiting lists, with a lottery system offering poor odds—a solution that lacks credibility in addressing affordability problems.

Even when resources are adequate, subsidies fail if governments don’t address supply constraints. Without removing zoning barriers, lengthy approval processes, and other regulations that restrict housing supply, subsidies only drive up prices further, as demand outpaces availability. Effective subsidies require both targeted support and systemic reform to avoid becoming counterproductive.

Bertaud also emphasizes that housing policy must connect income distribution with housing typology—the types of housing available, from high-rise apartments to informal settlements—to ensure that supply aligns with the needs of diverse income groups. For example, in Mumbai, lower-income households living in informal settlements consume far more land per unit of floor space than those in formal housing, reflecting inefficiency born of necessity. Aligning supply with spatial and economic realities can reduce these inefficiencies while improving access to adequate housing.

Location also matters—a lot. Affordable housing that’s far from jobs, schools, or transit isn’t truly affordable. When governments build housing in remote areas to save on land costs, they isolate residents from economic opportunities. This leads to failures like slum relocation programs, where residents abandon new housing in favour of informal settlements that are closer to urban centers.

It’s also important to appreciate how the economics of common “Transit-Oriented Development” practices can undermine this. New transit nodes, for example, can increase the land values within their vicinity and push affordable housing further from these important locations where land is cheaper.

So, what’s the alternative?

Adopting multifaceted strategies. Expanding land supply, relaxing restrictive zoning, and encouraging diverse housing types can all help. Policies like reducing minimum unit sizes or density caps can make it easier to build affordable homes for a range of household needs, depending on the context. Direct subsidies or income supports can also empower households to make choices that best suit their needs.

But, according to Bertaud, none of this works without reliable data on housing consumption, income distribution, and spatial access—again, data that many North American cities do not collect in full, including the City of Vancouver.

Ultimately, addressing housing affordability requires moving beyond the flawed, simple assumptions of the trickle-down theory. It demands a nuanced, data-driven approach that recognizes the structural and spatial inequities shaping housing markets.

In summary:

- Definition of a Theory: A theory explains patterns or behaviours based on evidence and reasoning. It is not a universal truth and is shaped by context, conditions, and biases. The trickle-down theory should be understood as a theory, not a law.

- The Trickle-Down Theory of Housing: Suggests that building higher-end housing frees up older, less expensive units for lower-income households through a natural filtering process. While appealing in theory, it often fails in practice.

- The Trickle-Down Theory of Housing Oversimplifies Housing Affordability: The ‘standard’ simple trickle-down theory fails to address the structural and spatial inequities in housing markets.

- Flawed Assumptions of the Trickle-Down Theory:

- Housing Supply is Elastic Across All Levels: Barriers like restrictive zoning and high construction costs limit the creation of affordable housing, leaving lower-income households underserved.

- Market Dynamics Ensure Equitable Distribution: Vacated units are often upgraded or repurposed for wealthier households, leading to a “trickle-up” effect rather than trickle-down.

- Homogeneous Housing Needs: Vacated housing rarely meets the size, quality, or location needs of lower-income households, making it inaccessible.

- The Market: The market is a mechanism without feelings or moral values. Markets prioritize profits, not inclusivity.

- The “Trickle-Up” Effect: Wealthier households outbid poorer ones for existing housing stock when supply is constrained, often displacing lower-income groups (e.g., gentrification or subsidized housing misuse). This can make affordability worse.

- Direct subsidies or income supports: Can empower low-income households, but their success hinges on sufficient resources to meet demand promptly; otherwise, waiting lists and lottery systems undermine their credibility.

- Effective subsidies must be paired with systemic reforms: Subsidies alone are ineffective without addressing supply constraints like zoning barriers and lengthy approval processes, as increased demand without adequate housing supply drives prices higher..

- Importance of Housing Consumption Data:

- Housing consumption includes the house type, size, quality, and housing location occupied by specific households.

- Lower-income households often consume inadequate housing, and policymakers cannot effectively address these deficiencies without detailed data.

- Connecting Housing Policy to Income Distribution and Typology:

- Housing type (e.g., high-rises, single-family homes, informal settlements) must align with the spatial and economic needs of different income groups for policies to be effective.

- Efficient land use and better alignment of supply with needs can improve access to adequate housing.

- The Importance of Location:

- Affordable housing far from jobs, schools, or transit is not truly affordable.

- Poorly located housing undermines livelihoods and leads to policy failures, such as abandoned slum relocation projects.

- Practices like Transit-Oriented Development can push affordable housing further away from jobs, schools, or transit if not done with care.

- A data-driven, nuanced approach is essential: The successful deployment of the trickle-down theory requires key data to craft effective, inclusive housing policies. Without proper data, governments can only “guess” the outcomes of their housing policies. This increases the risk of failure, or worse yet, making affordability worse (trickle-up).

- Key Policy Recommendations:

- Expand land supply and reform restrictive zoning regulations.

- Mandate diverse housing types to address diverse needs and avoid singular building types over large areas of urban land.

- Provide direct subsidies or income support to empower households to make tailored housing choices.

- Collect robust data on housing consumption, income distribution, and spatial access to inform policy decisions.

Some useful resources:

- Books:

- Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities by Alain Bertaud – Offers an in-depth critique of the trickle-down theory and explores the complexities of housing supply and demand.

- Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City by Matthew Desmond – While not exclusively about trickle-down theory, it highlights how simplistic market-driven approaches fail lower-income renters.

- The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein – Discusses structural barriers that undermine the assumptions of the trickle-down model.

- Selling Off California by Patrick Range McDonald – describes how deregulation and trickle-down narratives used in California under the guise of affordable housing resulted in the increasing rents and mass displacement of those in need.

- Articles:

- “Understanding Affordability: A Partial Picture” by Erick Villagomez – Spacing Vancouver – Attempted applying Alain Bertaud’s method to the Vancouver context and highlights that missing data necessary to do so.

- “Understanding Affordability: A Partial Picture—Bertaud’s Response” by Erick Villagomez and Alain Bertaud – Spacing Vancouver – Alain Bertaud’s correction of .

- “The Economics of Inclusionary Zoning Reclaimed: How Effective are Price Controls?” by Benjamin Powell & Edward Stringham – Critiques assumptions about inclusionary zoning, market elasticity and supply responses, which are central to the trickle-down theory.

- “Has Housing Filtering Stalled? Heterogeneous Outcomes in the American Housing Survey, 1985–2021” by Jonathan Spader — looks at how filtering can vary widely in response to local housing market conditions, and its implications for affordable housing strategies.

***

Related pieces in the S101S:

**

Related Spacing Vancouver articles:

- Understanding Affordability: A Partial Picture

- Understanding Affordability: A Partial Picture Bertaud’s Response

**

All pieces in the S101S:

- S101 Series: Introduction and Call

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Why is it so Confusing?

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: Net vs Gross Density•

- S101S: Understanding Residential Density: FSR, Building Setbacks and Height Regulations

- S101S : Understanding Shadow Studies: Why They Matter –

- S101S: What’s a Development Pro Forma—And Why Should you Care?

- S101S: Defining Public Space: The Basics

- S101S: Understanding Affordable Housing: The Trickle-Down Theory of Housing – Myths and Realities

- S101S: Describing Building Types: Why They Matter

- S101S: Describing Building Types: Formal and Use-Types

- S101S: Explaining Transit-Oriented Development: Benefits and Drawbacks

*

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.

One comment

Excellent article. Would like to forward it to BC current premier David Eby who is a big believer in the trickledown effect.