This two-part essay is a guest post by Lacey McRae Williams, an urban planner and artist who is happiest when she can use art to connect people while benefiting the natural environment. She grew up on the West Coast, in Victoria, so much of her influence comes from the ocean, mountains, and dense forests. She is currently volunteering with Lost Rivers and sits on the Don Watershed Regeneration Council.

My passion for art and design began at an early age; I would draw pictures before I would speak. As I grew up, I took art and painting in high school and always loved the visual aspect of learning much more than the written. Although I didn’t know the implications of my interests and where they would guide me in the future, I was drawn to clear, bright, simple and balanced forms of art. Many of my teachers actually described the art that I created as ‘architectural’, having been inspired by other artists.

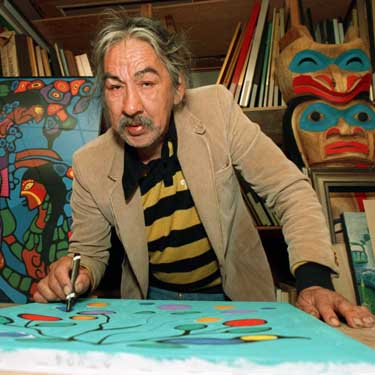

My first experience with Norval Morrisseau, an artist whose paintings I was fascinated with for their clarity and balance, occurred in Grade 9 when our class was assigned to mimic a painting that spoke to us. I chose one of Morrisseau’s ‘Circle of Life’ paintings due to its clean lines, vivid colour palette, and connected and unified shapes. The use of the circle and its repetition at varying scales lured me in and there was something about this work that I connected with. Until recently, that was my only remembered moment with Morrisseau’s work.

During my undergrad at the University of Victoria I spent the first two years in the History in Art program before switching to Social Sciences. For the duration of my four years I was drawn more regularly to courses that spoke of indigenous arts and cultures, becoming captivated by the legends fluidly embedded in each of the works. One course in particular focused on indigenous arts of the northwest coast, and I became familiar with the concept of the ‘form line’. This use of the line, particularly in Haida culture was used as a visual cue for connections and interrelationships. The form line wove layered ideas of persons, animals, and spirits together symbolizing the unity and synthesis of all things. This concept shattered my notion of what the line represented up until that point. Art teachers had always taught me that lines were used to divide space, and as soon as a blank canvas was marked with a paintbrush the one space that existed had now become two. I had never known that spaces could actually exist within theses lines themselves.

The natural progression after doing an undergrad was to follow with a Masters, which commenced two years later when I moved across the country from Victoria to Toronto to attend Ryerson in the School of Urban and Regional Planning. Almost immediately, I noticed the difference in ‘visibility’ of indigenous peoples and their cultures in the City of Toronto, as compared to Victoria. I began to research the reasons behind the lack of awareness of Toronto’s history with everyday people paired with the missing celebration of indigenous cultural identity throughout the streets of Toronto. To my surprise, I found that not only were many of the areas in and around Toronto inhabited by indigenous peoples before European settlers arrived, as had happened on BC’s coast, but that the ‘Urban Aboriginal’ population was, and still is, the youngest and most rapidly growing, increasing by 31% from 2001 to 2006 (Statistics Canada, 2011). Even at a national scale, over 50% of ‘Aboriginal Canadians’ live in urban centres (Muskrat Magazine, 2012), which burst another misconception that most indigenous populations live in rural areas and remote communities and therefore do not need to be consulted with in an urban setting.

My next question then was, Why is there no incentive to incorporate indigenous ways of knowing into the planning practice at an institutional level, and why is the ‘Urban Aboriginal’ population not readily engaged in the planning process?

Planning deals directly with land use, redevelopment and ownership which also happens to be the foundational issue for Canadians’ continued struggle with understanding indigenous peoples rights and beliefs in Canada – What do we do with the land? The fact that none of the major universities in Toronto offer courses on indigenous community planning is troublesome.

This is when Norval Morrisseau reappeared in my life, on my search for some of these answers. Morrisseau grew up in Beardmore Ontario, near Thunder Bay where he began his artistic career. His first paintings were sold in Toronto where he acclaimed almost immediate financial success and popularity for his unique and powerful message of the unfair political situation many First Nations communities had thrust upon them. Even after his death in 2007, his presence is still felt in Toronto. Places such as City Hall, museums, storefronts, and galleries showcase a variety of his works today. The locational connection between Norval Morrisseau and myself gave me a stronger feeling for a sense of place in Toronto, and I was determined to continue my research further.