This is part two of an essay by Lacey McRae Williams, read part 1 here. Lacey is an urban planner and artist who is happiest when she can use art to connect people while benefiting the natural environment. She grew up on the West Coast, in Victoria, so much of her influence comes from the ocean, mountains, and dense forests. She is currently volunteering with Lost Rivers and sits on the Don Watershed Regeneration Council.

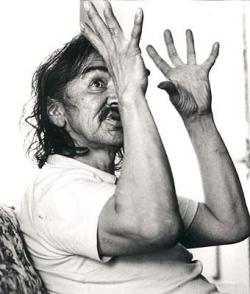

Norval Morrisseau, the Copper Thunderbird, is the Grandfather of the Woodlands style of art. This Ojibwa style of art is a purposive means of sharing traditional Anishinabe culture with ‘white’ people as he says, while also reconnecting modern day Anishinabek with their traditional heritage. His visual expression was never meant to exist statically, at one moment in time, but it was created and shared to combine contemporary art practices with the traditional Ojibwa culture, bridging a foundational gap between fellow Canadians and the Ojibwa people. Morrisseau explains,

“My art speaks and will continue to speak, transcending barriers of nationality, language and other forces that may be divisive, fortifying the greatness of the spirit that has always been the foundation of the Ojibwa people.

My goal is to break the barrier between the white world and mine. I wish only one thing, to be an artist and to be respected as one – and my paintings to be seen by all people” (Hill, 2006).

To better understand this deep connection with the land and the unity of all things from a traditional Anishinabe worldview, the following excerpt has been included from “The Land of the Ojibwe”, from the Minnesota Historical Society, 1973.

The fundamental essence of Anishinabe life is unity. The oneness of all things. In our view history is expressed in the way that life is lived each day. Key to this is the belief that harmony with all created things has been achieved. The people cannot be separated from the land with its cycle of seasons or from the other mysterious cycles of living things – of birth and growth and death and new birth. The people know where they come from. The story is deep in their hearts. It has been told in legends and dances, in dreams and in symbols. It is in the songs a grandmother sings to the child in her arms and in the web of family names, stories, and memories that the child learns as he or she grows older. This is a story of the spirit – individual and collective. There is another story of the Ojibwe people. This story tells of how European nations with overwhelming power and numbers swarmed across the land, reshaping it for themselves and destroying the natural balance within which the Anishinabe people had always lived. It tells of trade and wars and treaties, of laws and governments, and above all, of the long, stubborn struggle through which the Anishinabe tried to preserve their own ways and their own identity.

Norval Morrisseau’s paintings transform these words into vivid imagery that transcends the limits of literary language. His art reveals forgotten or unknown histories and shares the legends and stories of his culture explaining this connection to the land, the water, and the sky. As the form line does in Haida culture, the use of the line in Morrisseau’s paintings connects all persons, which he describes as plants, animals, and people. A collective constellation of shapes and colours unites people with the land, smudging the boundary between humans and nature.

The way that Norval Morrisseau uses the line to connect images with colours and reveal stories and cultural histories has the ability to indigenize planning practice. He uses the line not only to connect but also to reveal, both of which can be translated positively into contemporary planning practice. Just as artists have used the line to delineate space, planners and designers have used similar lines to separate land uses, people, and infrastructure. Where modernist planning succeeded temporarily at a regional scale, it failed wholly at a local scale. A line to a planner cannot be thought of in isolation, as connecting point A to point B. These lines must be blurred to accommodate regional connections with smaller-scale local community needs, while enhancing existing natural ecologies. How can a line, such as The Gardiner Expressway, that is used to connect people to their city, break up and divide small, vibrant communities in the same stroke, or remove people from a vast natural system, such as Lake Ontario, in this case? This type of tunnel-vision planning cannot continue to persist if we have the hopes of achieving connected, beautiful, vibrant and resilient cities where all residents feel as though their voice has been heard.

In terms of ‘upcycling’ these isolated planned lines, such as polluted buried streams, unfriendly hydro corridors, and overbearing elevated superhighways, a revelatory use of artistic interventions can shed light on these spaces of the ‘invisible’ city, or areas in which people have forgotten. The form of repurposing, reusing, and/or rethinking these spaces does not include an idea of erasure, as was common in modernist planning, but is instead a purposeful reinvention and revealing of these mostly industrial areas to commemorate a moment in time while inspiring residents of cities in flux. Art and visual communication, such as Morrisseau’s can be used as an evocative and educational tool to connect people of all cultures to their city, to start random public conversations and to arguably change the way in which planning plays out today. When done in a collaborative manner, these installations have the power to affect very positive transcendental change.

A great place to start in a very urban and concrete Toronto, is on the hidden natural watersheds buried beneath the city streets. Garrison Creek for example, which runs from just north of St. Clair between Dufferin and Bathurst to Fort York, where it entered Lake Ontario pre-lakefill, can been imagined under the patchwork pattern of parks tracing the original ravine. By using revelatory eco-art such as the example shown here, where a poem about loss and darkness is used to give Garrison Creek a voice, passersby can engage with this natural heritage system on a variety of levels.

A way to visualize other places in a city that could be transformed in a similar way is by imagining the city as a set of drawn lines. Roads, sidewalks, laneways, hydro corridors, waterfronts, rivers, railway lines, the list is almost endless. The importance here is that by connecting people to places in an artistic way, you in turn connect people to each other, likely strangers who wouldn’t have otherwise met.

The crux of my argument for rethinking the use of the line in planning practice does not exist only in a physical sense, but perhaps more importantly in a metaphoric sense. If we parallel the burial of streams with the burial of cultures, the separation of lands with the segregation of people, and the removal of nature with the deletion of outward appreciation and reflective humility, then the act of revealing these physical heritages can help us understand and respect the cultural ones. Planners are not the experts; we are merely conduits, in this position to convey the messages of the people in a way that can be translated in the physical environment.

One comment

Yes! I’d love to see a vision for a strong, indigenous urbanism. I presume urban-style clustering would relate to winter villages which as far as I can tell followed the ‘town square’ + sidestreets model that seems to be universal to humans.

It seemed so odd to me that one of the first acts of the Tsawwassen First Nation upon regaining control of their traditional land, was to build a box mall in a sea of asphalt parking. I couldn’t see the environmental or traditional connection there, nor any consideration for future generations beyond ‘grab the money and get out of Tsawwassen’.

I’d love Canada’s most prosperous cities in 2050 to be on traditional land, governed in an open democracy at a decentralised neighborhood/community level of a few hundred people, with First Nations dominating the local electoral register. That would be awesome.