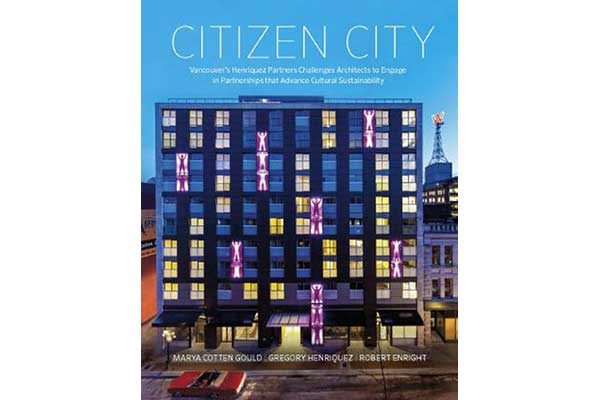

Edited by Robert Enright (Blueimprint Publishers, 2016)

“The projects compiled in this book are the culmination of over 25 years of architectural experimentation, which stand firmly with the advantage of being grounded upon the 50 years of my father’s practice. The aspiration of the book is to illustrate, through 10 specific projects, the latent potential within the architect’s role to not merely be a tool of others, but instead be seen as an activating force in the creation of our cities.”

Gregory Henriquez, from the Preface

There are not a lot of architects out there who can say they have worked on a building that had more than a thousand consultants during its design consultation process, but such was the case for the Woodwards solution that Henriquez Partners Architects forged back in 2010—closing a gaping wound in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside that had affected that neighbourhood since the late, great retailer vacated the site in 1993. Having had the good fortune to interview the late Jim Green from his office overlooking the project’s construction site back in 2008, it was he that explained to me the massive undertaking of consulting the project’s stakeholders, and how it was the patience and steadfastness of Gregory and his father that kept the project on course.

Of course, Henriquez Partners Architects had, at that time, already the long legacy that Richard Henriquez had established for his firm located for many years in the West Pender Building in downtown Vancouver. Gregory himself admits as much in the opening pages of this new book, Citizen City, that there are not many who can say they have had the good fortune to continue the legacy of a firm founded by one of the nation’s most formidable architects. But such was the case for the firm’s present director who, not only had to fill some fairly large shoes, but also immediately found himself with one of the city’s toughest challenges at the Woodwards site.

To say the outcome was a successful one would be a gross understatement, and as such is the subject of the firm’s previous book, Body Heat: The Story of the Woodward’s Redevelopment, also edited by Robert Enright, the editor of their latest book here. While the subject of the previous publication was an elucidation of the singular mammoth task of healing that physical and psychological scar in the city, this new book focuses on what the architect and author refers to as the “Children of Woodwards,” those projects that, one might say, have only been allowed to happen because of the success of Woodwards.

This new book now calls upon developers, governments, and non-profits to work together to find innovative solutions to the current Metro Vancouver housing affordability crisis, with several examples offered up and featured in the book as current and completed projects by the firm. One such example – the redevelopment of the Central Presbyterian Church in Vancouver’s West end – is being reimagined by the area’s Presbyterian church and its congregation to realize a multi-family residential development where the market units are subsidized to provide low-income housing. Another featured project in the book is the Westbank development at 6th and Fir Street in Vancouver, in which artists’ lofts, alongside a market residential tower, are provided for by a transfer of density from Woodwards.

Book-ended with two thoughtful pieces by Marya Cotton Gould, her opening essay “What is Citizen City?” examines the topic in relation to social sustainability, a notion strongly espoused by HPA. She notes that this issue was first enshrined by the United Nations in 1987, which in addition to addressing environmental sustainability was broadened to includes issues of poverty and hunger. Cultural sustainability, she notes, is a more recent addition to the lexicon, and is seen as an extension of social sustainability addressing issues of cultural preservation, including such notions as a ‘sense of place.’

“The vision of a Citizen City is one that transcends the traditional urban goals of economic stability and working infrastructure, and allows for inclusivity of its people, with a variety of economic levels, different cultures, and diverse identities. A Citizen City also provides and encourages open access to democratic and civic engagement, and develops cultural facilities and promotes cultural identity, thus enhancing a sense of community.”

The notion is not at all utopian—imagining a world where developer’s maintain their profit margin while providing community amenity—for in Metro Vancouver it has been going on since Concord Pacific handed over the Roundhouse Community Centre to the City of Vancouver Parks Board, and is now a mandatory component of large multi-family developments in the form of Community Amenity Contributions (CAC’s). Finding a developer who understands the value of giving back to the community, and who sees the CAC as a positive and not a negative has often been a source of friction between the architect, developer, and municipality.

Henriquez Partners Architects has found such a developer client in Ian Gillespie and Westbank, who worked with Gregory to realize Woodwards, and who understands that part of the business-as-usual land lift developers do every day means giving back to the public in the form of an amenity contribution. In Gould’s concluding essay, one realizes that to suggest that such a model for development could become the norm is no more far-fetched then that renewable energy and self-driving cars could soon become the norm.

The book also includes a candid interview Gregory, entitled ‘Letter To the Young Architect,’ in which he riffs on Rainer Maria Rilke, with editor Robert Enright asking him about the firm’s philosophy, aspirations, as well as the pitfalls and successes they have had along the way. The interview could have also included his feelings about moving into the office’s new subterranean digs below West Georgia Street, with the latest addition to the Vancouver skyline, the new Telus Garden, towering overhead.

Mostly, however, he stresses the need for the architect to be the catalyst to improve our social spaces, as a sort of champion for cultural sustainability, best equipped to bring together the client and community together to talk and responsibly shape our urban environments.

“Prior to Woodward’s, I saw developers as the type of people I didn’t want to have lunch with, let alone work with. What I didn’t understand was the power of the development process to do good in the world if properly harnessed. Through Woodward’s I realized that if you have an enlightened civic government; if you have a developer who is willing to do good in exchange for appropriate financial compensation; if you have a community willing to engage in that dialogue; and if you have a project of substance that could actually benefit from these relationships, then something meaningful may happen.”

Whether to champion affordable housing or accommodate a company looking for their new corporate headquarters to be built to the most current environmental standards, the projects presented in Citizen City represent some of Henriquez Partners Architect’s finest work to date. In addition to providing possible solutions to our current affordable housing crisis, the book also is a timely and meaningful discussion about the role of the client, community, and public as collaborating citizens in this microcosm that is present day Vancouver, and in which the firm is currently based.

Overall, Citizen City and its ten projects are a thoughtful response to the call for shared social responsibility in our cities and how now, perhaps more than ever, the architect’s skills are needed to lead the conversation about how we will live and build in them.

***

Sean Ruthen is a Metro Vancouver-based architect and writer.

3 comments

Thank you Sean for you thoughtful and supportive review. Truly appreciated.

Does this book explore the concept of Cohousing in Vancouver? Developers who have a social conscience can contribute their CAC to the common space in these developments as a way of giving back to intentional, multigenerational communities that are striving to reduce social isolation between neighbours.

The Toronto Public Library has “Body Heat”

http://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDM2676725&R=2676725

Have a look or borrow a copy today.