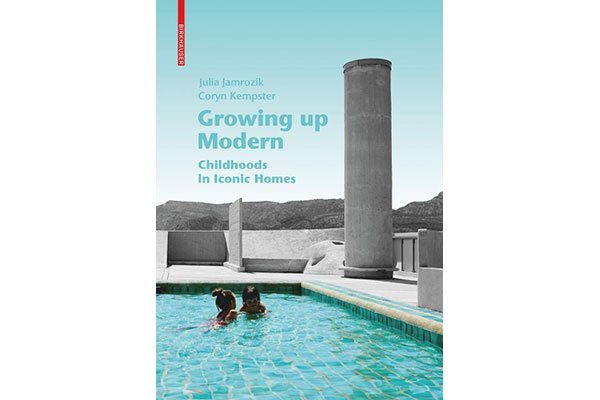

Written by Julia Jamrozik and Coryn Kempster (Birkhäuser Publishing, 2021)

Publishing these stories allows both architects and those interested in architecture to view these iconic buildings from another perspective, prompting readers to imagine design through the eyes of children and more generally through the eyes of the user. Growing Up Modern has been to challenge ourselves, and our audience, to better understand the visionary and political agency of architecture, not by denying the fact that architectural spaces are functional – that their histories are multifaceted and not controlled by the architect – but precisely by embracing this reality.

- Julia Jamrozik & Coryn Kempster

In Growing Up Modern: Childhoods in Iconic Homes, two Canadian architects who met while working in Basel at the firm of Herzog & de Meuron have collected fascinating testimonials from a diversity of former occupants of four canonical modern residences designed by well-known architects Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Hans Scharoun, and J.J. Oud. The book serves as a reminder that despite modern architecture’s high status in glossy monographs and magazines favouring sublime typologies of larger buildings—office towers, grand galleries, and theatres—there still exists in the canon some ground-breaking examples of humble private homes whose inhabitants still have much to tell.

That we could still learn from homes designed and constructed in the 1930’s in our ongoing modern age is the intent of Julia Jamrozik and Coryn Kempster, who have tied architectural theory to the fields of psychology and sociology. And certainly, with both Covid and climate change currently rearranging society’s relationship with their living arrangements, there is also much here for young parents who also happen to be design professionals—as the authors of the book include raising their newborn as part of the book’s narrative.

As Jamrozik and Kempster remark in their introduction, our current housing crisis, both locally and nationally, is something the modernists were grappling with ninety years ago. Quoting Le Corbusier from Toward an Architecture (1927):

The problem of the house is a problem of the epoch. The equilibrium of society today depends upon it. Architecture has for its first duty, in this period of renewal, that of bringing about a revision of values, a revision of the constituent elements of the house.

Architects like Le Corbusier have been very vocal that housing is at the epicenter of human experience. He may even have anticipated the horrible outcome of architectural commodification if left to the devices of high finance coupled with inept municipal administrators and bean counters.

While Scharoun’s Schminke House (1933) and Oud’s Weissenhof Estate Row House (1927) may be less familiar to some, any designer and architect worth their salt knows both Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation (1953) and Mies van der Rohe’s Tugendhat House (1930). With the latter turned into a museum and gift shop—as well as the subject of several books—Corb’s Unité is still being used for its original purpose of multi-housing, with the ongoing use of its rooftop pool providing the image that graces the cover of the book.

Unité d’Habitation was the great master’s response to the housing crisis following World War II and it would be replicated the world over for better and for worse, with perhaps the worst iteration being Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis, Missouri. With all of Unité’s community-building amenities—gardens, shared loggia, play parks, and pool—stripped away to bare-bone housing, the housing project quickly turned into a ghetto that needed to be demolished in 1976, after only five years of existence. Overarchingly, the authors’ focus is to provide an oral history of how important (or not) these houses were for their occupants, and more specifically, the influence these physical environments had on their childhood memories while growing up in them.

In the book’s introduction, we are given a brief understanding of child psychology and the importance of a child’s first home in the development of their understanding of architecture, something which will accompany them as they mature to adulthood. Gaston Bachelard’s seminal Poetics of Space is often quoted by the authors, given that throughout his text he refers to the notion of oneirism, or daydreaming. As they cite him, “over and beyond our memories, the house we were born in is physically inscribed in us,” and further on, “the house is one of the greatest powers of integration for the thoughts, memories, and dreams of mankind.”

As an addendum to the book, the authors have also offered a wonderful self-testimonial of their road trip and how they set out in 2015 (during a heat wave) with their nine-month-old toddler to visit the subject houses of their books. They noted how their son would be too young to remember the trip in later years, but that perhaps still the influence of these curious modern houses would maintain a hold on his psyche:

We were thinking of the kids, now old enough to have children and grandchildren of their own, who all graciously agreed to speak with us and who, as babies, also must have crawled through these same spaces and played boisterously within them. They, unlike their parents, never chose to live in avant-garde buildings. We thought, naively perhaps, that their perceptions would have been purer and their opinions less biased than those of the clients themselves. They were the guinea pigs of the Modernists’ claims that architecture had the capacity to deeply affect inhabitants, even make them “better people.” Did they believe that these buildings influenced them and who they have become?

Of all the ‘interlocutors’ Jamrozik and Kempster interviewed for the book, the above was most certainly the case for Gisèle Moreau, who grew up in the innovative Unité housing complex and lives there still—providing vivid memories of using the shared community spaces with the other children living in the building, including the rooftop pool from the cover. Other photos included in the book show children climbing up a tilted concrete plane, also on the roof (one of Moreau’s favourite photos), set beside another photo of children playing in the building’s nursery. Having inherited the unit she grew up in from her parents, she is a rare instance of one who has been able to continue to live in the space they grew up in.

In their interview with Ernst Tugendhat, he admitted at 85-years-old he had little memory of living in the house and was still slightly traumatized by his family being forced to flee the house and Czechoslovakia to escape the Third Reich when he was only eight. He revealed to the authors that it is possible to live in a house designed by a world-famous architect and be totally indifferent to it (also fascinating is his story of how the original house furnishings traveled to Switzerland with them in their escape). His testimonial is then perhaps the most Bachelard-like, as his return to the house prompted more haptic and visceral memories rather than literal ones, such as the sound of their father’s car horn in the front yard, or the cooling feel of a hard stone surface on a summer’s day.

The remaining two houses also offer up riveting testimonials, with one focused on a more communal, tightly urban context in the case of Oud’s row-house, while the Scharoun house interview was with someone who lived in it until they were eighteen years old, such that she still dreams of its interiors and exteriors to this day. Many more of the stories from these building’s childhood occupants are equally fascinating, and reveal the fourth dimension of architecture: how, beyond the design and construction of buildings, architecture embodies the history and memories of its occupants.

As recipients of the Architectural League Prize in 2018, Growing Up Modern is most certainly the first of many more books to come from Jamrozik and Kempster. The breathtaking scope with which they have captured and documented their subject matter is to be applauded, including hundreds of photographs—some archival and some from their own cameras—along with original scanned drawings of the houses, with each house accompanied by a memory diagram mapped during their interviews. And certainly having their nine-month-old along for the ride would’ve helped to break the ice during the interviews, especially those needing to be translated.

Even more important than architecturally documenting these houses as heritage objects is recognition of their function as storehouses of the memories of their former (and current) occupants, representing such vivid memories that in Gisèle’s case she can to this day remember where she was in the Unité when she heard the news that Le Corbusier had passed away. As one of their sources noted in their concluding observations, this is an untapped stream of study on post-occupancy, as it provides an oral history of those occupants that had no choice but to be in these houses and provides us with a small window into the world of architecture seen from the perspective of a child.

A highly commendable and readable work, Growing Up Modern will soon find its place in discussions of social sustainability, as we most certainly need to continue to nurture not just individuals but families with children, knowing that the first impressions of those toddlers towards our built environments will have a lasting impact. As such, this book can be enjoyed by architects and designers, child psychologists and sociologists, as well as educators and young parents.

***

For more information on Growing Up Modern, go to the Birkhäuser Press website.

***

Sean Ruthen is a Metro Vancouver-based architect and the current RAIC regional director for BC and Yukon.