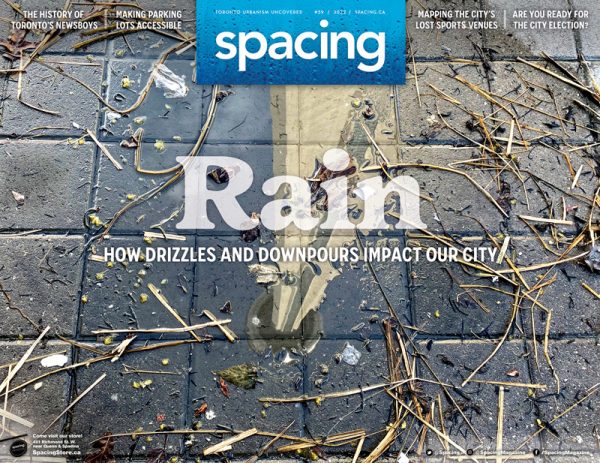

I’ll place a bet that you cursed rain sometime this season. Spring is rainy, but it’s not yet warm enough for the rain to be a relief from drought or heat. Instead, it’s wet and grey and still a bit chilly, putting a damper on outdoor activity just as the weather starts to get warmer and we long to get out in the open.

There are endless songs about rain, and most of them are not happy. Rain, the music tell us, is the symbol of melancholy: “Who’ll stop the rain?”; “A rainy night in Georgia”; “Listen to the rhythm of the falling rain … let me cry in vain”; “What a cold and rainy day, where on earth is the sun hid away?” We long to banish it, and it’s the sun we sing of as a sign of hope: “I can see clearly now, the rain has gone”; “The sun’ll come out, tomorrow.”

Rain is a pain for cities, too. We build over soil and creeks to create our houses and our roads, and then, having blocked the outlets nature relies on to absorb precipitation, we have to also build places for it to go. Rain management shapes every aspect of the city. Our buildings are structured to shed it, our streets, sidewalks and driveways are sloped to manage it, and a vast, complex artificial drainage system that literally undergirds the city is dedicated to diverting it into the nearest body of water.

Until recently, we did the minimum in Toronto, and then complained when things went wrong. Basements flooded, rivers overflowed, roads were swamped, slopes eroded, and sewage was swept up in stormwater and dumped on the lakeshore.

In recent years – pressed by urban expansion, by aging infrastructure, by environmental awareness, by the looming presence of climate change – we’ve stared to take managing rain more seriously. The new developments at the mouth of the Don River are being bordered by berms to protect them from rising waters. Homeowners are encouraged to grow absorbent gardens and disconnect downspouts towards yards or rain barrels. Updated building codes include green roofs and other water management techniques. The city is exploring infrastructure that retains rainwater, buttressing slopes and streams, and rebuilding its sewer system. The whole endeavour is a big, expensive task, one that requires both attention to small details and investment in huge projects, because managing rain is one of the fundamental challenges faced by cities.

But rain is also a necessity.

The few songs that are positive about rain are about need: “And I miss you, like the deserts miss the rain”; “I need you like water, like breath, like rain.” We need that rain to keep our city green, to water our parks and gardens and street trees, to wash from the air and the ground the dirt our civilization endlessly generates, to renew the lakes and aquifers that provide us with the water essential to life and to health. Without it, we witness the city shrivel, dry up, lose colour. We may complain about the rain when it comes, but when it holds back for too long, we miss it. It’s a dysfunctional yet dependent relationship.

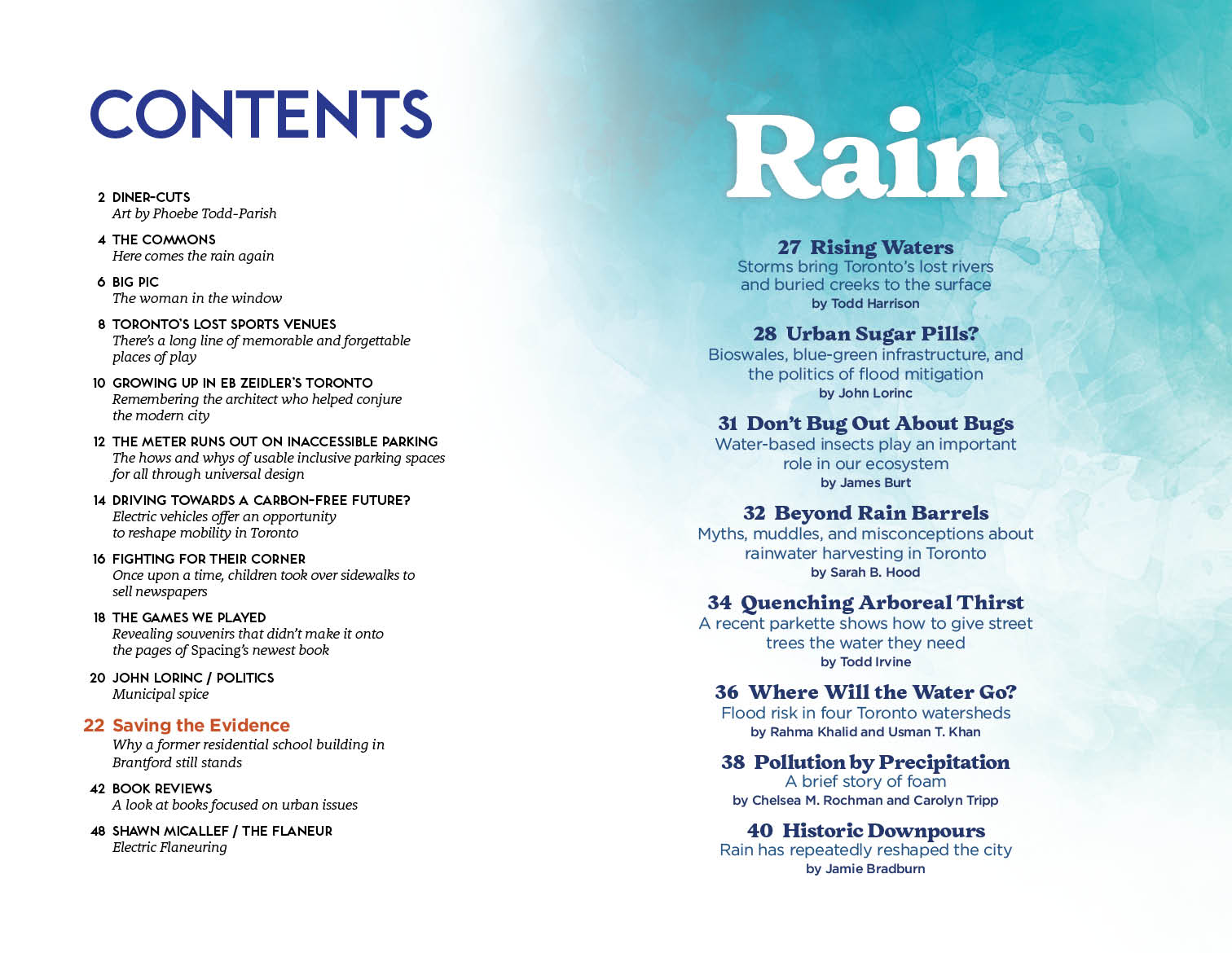

Yet difficulty inspires creativity. I’m really pleased with the range of contributions we received for our cover section on rain. The pieces are short and long, personal and scientific, illustrated and cartographic. They cover disaster and pollution, construction and infrastructure, trees and insects. They explore plans and regulations, discoveries and debates, old archives and contemporary research. It’s a kaleidoscope covering many of the different ways rain interacts with the city, and both the challenges and the benefits that result.

But we open, with Todd Harrison’s meditation on how rain evokes our hidden geographies, with a hint of the delight that rain can bring. Rain may be difficult, but it can also be beautiful. The softness of the air and the light as you walk through a delicate drizzle, too gentle to need an umbrella. Running to shelter to watch a brief, spectacular, cleansing summer downpour. The ephemeral beauty of the occasional rainbow. And that wonderfully-named petrichor, the smell of plants and soil after rain, their post-coital emanation after their thirst has been satisfied. It may be a difficult relationship, but its challenges are compensated for by moments of joy.

Elsewhere in the issue, Beth Simons explores the history of newsboys in Toronto – children who employed themselves selling newspapers on streetcorners in the early twentieth century. Artist Bill Perry shares a remarkable 360-degree photograph collation he took – while perched on the roof of the Church of the Holy Trinity – of the old Eaton’s complex just before it was torn down for the Eaton Centre. In our feature, Mnawaate Corbiere looks at the decision of the communities of Six Nations and New Credit to transform rather than demolish a former residential school near Brantford. Plus we feature the potential and pitfalls of electric vehicles, the accessibility of parking lots, the legacy of Eb Zeidler, out-takes from our latest book, and more.

The issue is available now in fine bookstores, and at the Spacing Store at 401 Richmond St. W, Toronto. If you’re a subscriber, it will be in your mailbox soon if it hasn’t landed already (and if you’re not, consider becoming one!).