According to The Living City Report Card released on January 31, “77 per cent of urban areas within TRCA’s jurisdiction still do not have adequate storm water controls”. That is significant not only for our lake and rivers which characterize the natural environment but also for human health and economic development. Though the city faces many environmental challenges, storm water management is one challenge that is in need of renewed attention and focus. The Living City Report Card gave storm water management in Toronto a failing grade of an F due to the need for significant investment and improvements required to improve or retrofit Toronto’s infrastructure.

Poor storm water infrastructure is not a unique situation to Toronto. Most older cities have aging sewer systems that were built in the early stages of city development. Common sewers – those that combine both sanitary runoff and sewage – cause issues from overflows during periods of high rain or snowfall. When these systems were initially built it was assumed that the sewage would be diluted sufficiently so that even if there were overflows there would be no lasting effects. As cities grew and demands on the systems increased overflows became increasingly common and concentrated. The overflow goes into lakes and rivers and is composed of human waste in addition to pesticides, road salt, gas and other toxins that go down the drain.

Sewers do not receive much attention for many different reasons including complexity, cost and the simple fact that it’s a vital infrastructure that no one sees. Cities can approach the problem in two ways: at the source or the end of pipe. At the source there are numerous methods in which waste water that goes into drains can be reduced. Green infrastructure can make a significant difference. Green roofs, permeable parking lots, rainwater harvesting or roadside swales capture the water that would have gone into the sewers. Reducing the volume of storm water can help reduce the possibility of spills, bypasses or overflows.

Toronto’s Wet Weather Master Flow Plan, which was adopted in 2003, is an attempt to incorporate both source and end of pipe solutions over the next 25 years. A combination of educational campaigns about proper disposal and infrastructure upgrades make the plan diverse and comprehensive, although the effectiveness of this plan is yet to be seen. According to data from Toronto Public Health from 2003 to 2007 the total days that Toronto beaches were closed over the summer months did not change significantly. Water quality changes did not follow any linear pattern and spikes or dips were more likely due to the weather during that particular summer. The problem is complex and relies on individual behaviour as well as infrastructure. The results of the Wet Weather Master Flow Plan may not be seen for many years to come.

If a home owner chose not to upgrade degrading plumbing or a sagging roof most folks would say that they were not responsible home owners. The equivalent is happening in Toronto. Infrastructure that is long overdue for an upgrade is only slowly being addressed. Moreover, opportunities to help ease the burden on sewer systems like Green Roofs, are being delayed or programs such as downspout disconnection are lapsing. Storm water management solutions can be so multi-faceted that the benefits would go far beyond merely cleaning the water. It is time that city management takes a good hard look at their failing grade and make a decision about how to best invest a limited budget.

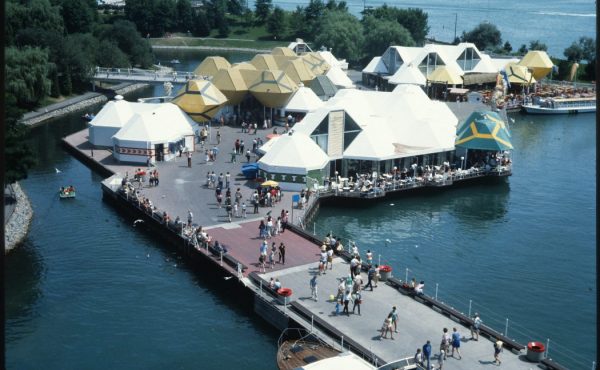

Photo by aubs

6 comments

Walk through the ravine under Ellesmere Rd. and you can see the effects of flash floods from rain pouring of hundreds of thousands of driveways. It looks like something out of a glacier track.

http://maps.google.com/maps?sll=43.660172,-79.379525&sspn=0.047316,0.0739&ie=UTF8&ll=43.778763,-79.207585&spn=0.011573,0.017681&t=h&z=16

A little known fact about the Wet Weather Flow Master Plan. At the end of the discussions, three viable options were presented costing 1, 3, and 10 billion dollars. The 1 billion dollar plan would cover the bare minimum necessary to get the job done, the 3 billion dollar plan would be able to to do the job well plus some contingency and the 10 billion dollar plan was really a what if we got everything we needed plan. The city opted for the bare minimum plan which means about $40 million to be spent every year for 25 years. In 2030 we’ll still be stuck with combined-sewers but the flows will be diverted into big tanks such as the ones under eastern and western beaches.

It is disappointing that the current administration views downspout disconnection and green roofs as superfluous. These are source controls which for storm water are much better environmental options than end-of-point solutions such as diversion tanks.

P.S. it is road side swales, not swills.

Thanks for the comment (and noting the error)!

Thought this NYC Dept. of Environmental Protection rule might be of interest to you (h/t http://swimmablenyc.info/): DEP Launches Parking Lot Stormwater Pilot Program, http://www.nyc.gov/html/dep/html/press_releases/11-04pr.shtml

The City of Toronto has taken initial steps to use innovative technologies such as green infrastructure to create source controls for stormwater. On the Queensway, for example, they have installed a “Proof of Concept” stormwater source control using Silva Cell technology.

At this site, Toronto Water is combining rainwater, trees and uncompacted soils into one integrated system. They have done this by using the modular Silva Cell to create what is essentially a giant underground rain garden, filled with a bioretention soil mix, beneath the sidewalk and parking lay by. Surface rainwater is then run in from the street and sidewalks through the existing catch basins and then into the Silva Cells. Just like a day lighted rain garden, the soil in the Silva Cells will retain, detain and clean the stormwater from daily rainfall events.

Street trees are also planted in the system and aid in stormwater management. As the trees mature they too will start to evapotranpirate stormwater from their root structure and interdict large volumes of stormwater in their canopies. The Queensway Stormwater source control might be as much as 25% more efficient in 15-20 years as it is today due to the growth and maturation of the trees

This system has been operational since 2008. The city plans to have monitoring equipment up and running this spring so that they can get real-time quality and time data for water in and water out.

The Silva Cell technology is also being used on Bloor St. and the Central Waterfront to provide large volumes of soil for urban trees under the sidewalks and manageme stormwater at-source.

For more information about these and other Silva Cell installation, please visit the DeepRoot website: http://www.deeproot.com/products/silva-cell/case-studies.html

There was a fair bit of less-fulfilling info, and some larger gaps in analysis. Not the bikes being barely mentioned, as a NOW letter with my name on it indicated, but more importantly, with CO2 emissions, we’re not counting any concrete use, estimated at 5% of global CO2 emissions

With the wastewater issues, we are not thinking of pavement disconnection, and we’re also not looking too much at the quality of that runoff. I’m quite appalled at how many larger oil spills I’m seeing on the core Toronto roads, but if the war on the car is over ie. we’re back to the war on bikes and peds and transit users, how can we get the oil cleaned up out of wastewater?