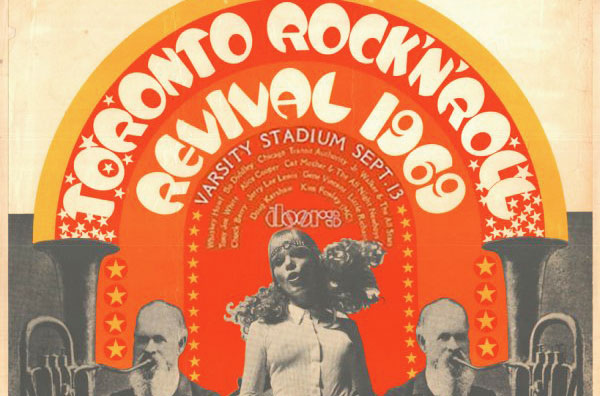

At first, no one believed it was really happening. It sounded too good to be true. The Toronto Rock ‘N’ Rock Revival Show was going to be a massive, thirteen-hour spectacle in tribute to old-timey jukebox rock & roll. The line-up was going to feature some of the greatest rock stars that had ever lived: a mix, mostly, of old greats from the 1950s and up-and-coming young stars. Little Richard. Chuck Berry. Alice Cooper. Jerry Lee Lewis. Bo Diddley. Chicago. The Doors. Gene Vincent. Junior Walker & The All-Stars. But tickets for the festival hadn’t been selling well at all. People in 1969 weren’t really all that interested in rock & roll from the ’50s. They were into psychedelic rock now; Woodstock had happened less than a month earlier. So it seemed pretty convenient when the rumour started: that John Lennon was going to show up with Yoko Ono, Eric Clapton and The Plastic Ono Band in tow.

Pfft! No way they got one of The Beatles. John Lennon hadn’t performed at a rock show in front of a big crowd in more than three years — not since The Beatles quit touring. When the rumour started, radio stations refused to believe it. And so did everyone else.

But then, in Detroit, a radio DJ got a hold of a recording of a phone conversation between the organizers of the festival and Yoko Ono’s assistant: they were booking the plane tickets from London to Toronto. The DJ played the tape on the air and suddenly, at the very last minute, it seemed as if Lennon might actually be coming. People rushed to buy tickets. In just a few hours on the afternoon of the show, it went from a financial disaster to a sell out.

Still, the ticket holders didn’t know the whole truth: even the organizers weren’t completely sure Lennon would actually come. The Beatle woke up that morning at home in England, nearly six thousand kilometers away. He’d only known about the show for a couple of days, when he got a phone call from Toronto asking if he and Yoko would be willing to emcee the show. John would get to introduce Yoko to all the rock & roll heroes of his childhood and they would be able to use the show as a chance to promote peace. In fact, it would also become known as the Toronto Peace Festival. This was just a few months after they’d recorded “Give Peace a Chance” in a Montreal hotel room and just a few months before they launched their famous “War Is Over” billboard campaign. Lennon agreed. In fact, he didn’t just promise to come, he promised to play.

It really was unbelievable. The Beatles were still the biggest band on Earth — just a month earlier, John, Paul, George and Ringo had finished recording Abbey Road, which would turn out to be one of the greatest albums of all-time. But the end was near. They weren’t getting along like they used to: they bitched at each other in the studio, fought over the business of Apple Records, grumbled about the time Ono was spending in the studio. Lennon was looking for a new creative outlet. And the Toronto show would help give him one.

There was, however, a big problem: Lennon didn’t have another band. He and Yoko had recorded together under the name “The Plastic Ono Band”, but that wasn’t a real band at all. It’s just what they called anybody who happened to be playing with them. “YOU are the Plastic Ono Band” was their official slogan. That meant Lennon only had a couple of days to put together an entire new band from scratch.

Of course, John Lennon had an easier time finding musicians than most people would. He convinced Eric Clapton (who had played on The Beatles’ White Album) to come play guitar. Klaus Voorman (who had been friends with The Beatles since their early Hamburg days and played bass in Manfred Mann) said he would come too. Drummer Alan White (who would later play in Yes) was the final piece: he agreed as soon as he realized it wasn’t a prank call — that really was John Lennon on the other end of the phone.

But getting a few musicians together was one thing — actually getting on the plane and going through with his first gig in three years was another. They say Lennon was a nervous wreck. On the day of the show, John and Yoko didn’t show up for the band’s flight from Heathrow. The plane left for Toronto without The Plastic Ono Band on board.

That was a MAJOR problem for the festival organizers. And not just because of all the angry ticket holders they’d have on their hands if Lennon didn’t show up. The promoters were much more worried about the angry biker gang they’d have on their hands.

You see, over the course of 1960s, a biker gang called The Vagabonds had become a major force in the Toronto rock scene, doing their whole violence and drugs and horrifying misogyny and crime and riding motorcycles thing. They’d managed to sort of, um, “convince” the guys putting the show together that The Vagabonds should be allowed to escort John and Yoko from Pearson Airport (on the outskirts of the city) to Varsity Stadium (downtown, at Bloor & St. George). The Vagabonds arrived in force: 80 bikers, all of them excited to be the honour guard for one of the Beatles. They were not going to be happy if it fell through.

In the end, they say Eric Clapton saved the day. He got on the phone with Lennon and told him in no uncertain terms that if Eric Clapton had to be at the airport lugging around all his gear, so did John and Yoko. Lennon was finally convinced to go through with it. The band was going to be a few hours late, but the bikers were okay with that: they’d go pick up The Doors first and then make a second run. Meanwhile, The Plastic Ono Band finally got a chance to have their first ever rehearsal: on the plane, without amps or drums, struggling to hear themselves over the roar of the engines as they flew across the Atlantic on the way to their very first gig.

That wasn’t the show’s only last minute hiccup, either. Just a few days earlier, the promoters had managed to land another 1960s icon: D.A. Pennebaker. He was the greatest rock ‘n’ roll documentary filmmaker of, well, ever: the guy who had filmed Bob Dylan in Don’t Look Back and made the wildly successful documentary about the Monterey Pop Festival. But there were some last minute money issues in Toronto. Pennebaker arrived at the stadium on the day of the show and started setting up his equipment — even watched as the first acts took to the stage — but he still didn’t have permission to film anything. He watched helplessly as Bo Diddley — who was supposed to be one of the centrepieces of the film — began his set.

Finally, the permission came through. As Diddley came out for an encore, the cameras started rolling. So that’s how Pennebaker’s movie — Sweet Toronto — starts: with the sound of Bo Diddley’s electric guitar playing the iconic chords from his massive, self-titled, 1955 hit. When you finally get a good look at Diddley on stage in the film, he’s in a suit, guitar in hand, dancing under the hot sun with his backing band. He calls out the refrain and thousands upon thousands of people roar it back to him: “Heyyyyyyy Bo Diddley!” It’s enough to give you chills. And the build up to that moment in the film is even more extraordinary: as those first chords repeat themselves over and over again, the footage cuts away to the airport, where John and Yoko and the rest of The Plastic Ono Band are arriving. They find a limousine waiting for them — along with the surprise of 80 enthusiastic bikers. As afternoon turns to dusk, The Vagabonds escort them down the 401 and into the heart of the city.When they got to Varsity Stadium, John and Yoko headed into the dressing room; they had a few hours to wait before their turn on stage. Meanwhile, the other acts on the bill — egged on by the cameras of one of the most famous documentarians of all-time — were giving some of the most amazing performances of their entire careers.

Robert Christgau, “Dean of American Rock Critics”, was there that day. And since he’s one of the greatest rock writers ever, I’ll defer to him:

“The sun was fading… by the time Chuck Berry appeared. Berry is the best all-around showman in rock and roll. He is probably in his forties by now, nobody really knows, and duckwalking across the stage takes more out of him than it once did. But the cameras turned him on. Pennebaker was still contorting himself and shooting wild from the knees and belly, but Berry matched him twist for turn, and did three duckwalks, and mugged shamelessly for the cameras. In what several experienced Berry-watchers adjudged one of his finest shows ever, he stayed on for over an hour, finishing at twilight.”

In fact, as the day wore on, it was clear the show was beginning to be a pretty big deal for all of the older performers. Just a decade earlier, they had been some of the biggest — and first — rock stars the world had ever seen. But now, at the end of the ’60s, none of them was as popular as they had once been. Straight-up, hard-rocking rhythm and blues had been replaced by psychedelic jams. Rockers had been replaced by hippies. Now that Lennon and Pennebaker had turned the Toronto Peace Festival into something more than just a revival show, those old jukebox stars were taking full advantage. The crowd danced and laughed and sang along. It makes for remarkable footage in Sweet Toronto: those shaggy, long-haired kids of the late ’60s, with their big sleeves and big hats, their vests and bare chests, smoking pot and blowing bubbles to old-timey rock & roll, shaking their hips, doing the twist, singing and clapping along to the songs that kids their age had been listening to more than a decade ago, their faces glowing. All smiles.

After darkness descended, Little Richard came out with his bouffant hair do and bright, tight, shiny, silverwhite pants, his shirt covered in mirrors. During “Good Golly Miss Molly,” he leaped on top of the speakers, dancing like a disco ball, took his shoes and his necklaces off, and then hurled them all into the crowd. During “Jenny, Jenny” he stripped to the waist, bouncing, sweaty and frantic, twirling his shirt above his head before launching it out into the mass of the audience. “Long Tall Sally” was a blistering, bare-chested frenzy. He played “Tutti Frutti” twice in a row. “Rip It Up” three times. Christgau was blown away: “Little Richard, resplendent in mirrors and pompadour and with makeup covering not only his face but his neck, put on his usual orgy of self-adoration. He was magnificent.” The Star called him “absolutely electrifying.” The Montreal Gazette called him “rock and roll personified… You name it, he sang it — and it was all just as good live in a stadium filled with long hair and pot smoke as it was in a finished basement with white socks and smuggled beer.” As Richard tore through his version of “Keep A-Knockin’,” hippies made out on the grass. A Canadian flag waved above the crowd. By the end of the set, he had picked people out of the audience to dance on stage with him. “Ladies and gentlemen, you are looking at the true rock & roll!” he shouted. “The 1956 rock & roll!”

Some critics point to that day as the moment the 1950s became cool again. After appearing on stage in Toronto, the old jukebox stars, some of whom were having trouble getting gigs, started being asked to tour again. Soon, Little Richard was back on the charts; he was featured on albums by young bands like Canned Heat and Bachman-Turner Overdrive. Bo Diddley was opening for groups like The Clash as late as 1979. Jerry Lee Lewis found himself back on the charts, too. And so did Chuck Berry. In fact, he would get his first ever #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1972. Today, 45 years after the Toronto Rock ‘N’ Roll Revival Show, Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis are all still touring.

And while the festival was reliving the 1950s, it was also heralding the very beginning of the 1970s.

Alice Cooper played that night too. He wasn’t a big name at that point, but the Toronto Peace Festival would prove to be his most famous performance ever. His band appeared in makeup, long hair, leather and ripped stockings, playing their strange, theatrical prog-rock. At the climax of the set, they hurled themselves around the stage, tearing apart the gear, as their instruments screeched and moaned. Cooper kicked a football out into the audience, smashed a watermelon with a hammer and then heaved it, too, out into the crowd. The band broke open a few pillows, filling the air with feathers, and used big tanks of CO2 to blow them out over the audience. And then, well…

Nobody seems to be entirely sure where the chicken came from. Cooper claims that an audience member threw it on stage. Other people say the band brought it with them. Either way, you can see what happened next in Pennebaker’s footage of the show: Cooper picked up a live chicken from the stage and launched it out into the crowd. “I figured: it’s a bird,” he explained in an interview decades later. “I’m from Detroit, I don’t know, a chicken’s got wings, it’ll fly — and I threw it back in the audience figuring it would just fly away. Well, it went into the audience and the audience tore it to pieces.”

By the time the newspapers hit stands the next day, some headlines were claiming that Cooper bit the head off the chicken himself and drank its blood. In the morning, he’d get a call from Frank Zappa asking him if it was true. When Cooper explained what had happen, Zappa told him, “Well, whatever you do, don’t tell anyone you didn’t do it.” It is still, to this day, one of the most infamous stories in all of rock & roll history. Alice Cooper’s “Chicken Incident” is hailed by many critics as the birth of shock rock.

Meanwhile, John and Yoko and The Plastic Ono Band had been backstage during all of this, waiting for their turn to perform. The tension was eating away at Lennon. It had been so long since he played a real show — and his first time back was going to be in front of some of his biggest musical heroes. “I threw up for hours before I went on,” he admitted. (Eric Clapton later suggested that may have had something to do with all the coke Lennon was snorting.)

Finally, at midnight, it was time. The emcee for the night was Kim Fowley — a super-famous radio DJ from Los Angeles — who had an idea he thought might help to calm the Beatle’s nerves. He had the stadium lights lowered, so that it was completely dark. And then he asked the crowd to light their matches. As Lennon, all long hair and shaggy beard in a white suit, stepped out onto the stage, he was greeted by a sea of flickering light. Thousands of tiny flames glowed all around the stadium. “It was fantastic,” he remembered later. “The lights were just going down. This was the first time I ever heard about this — I’d never seen it anywhere else — I think it was the first time it happened.”

He was still nervous, though. “We’re just going to do numbers we know,” he told the crowd, “you know, because we’ve never played together before.” And then The Plastic Ono Band launched into “Blue Suede Shoes”. It was big rock classics like that at the beginning of the set: the songs the band members had heard their heroes sing back when they were young — some of those heroes, the same ones who were now watching from backstage. They were the kind of songs that made Lennon want to start The Beatles in the first place. The kind of songs they started out playing in their earliest days, at the smoke-filled Cavern in Liverpool and in the rough nightclubs of Hamburg in the early 1960s. Back when it was all still fun; before everything got complicated.

It was an emotional moment. Watching from backstage, Gene Vincent had tears streaming down his cheeks. He’d first met Lennon and The Beatles back in those Hamburg days, when the Fab Four were still just starting out and Vincent was already a star thanks to “Be-Bop-A-Lula”. The first record Paul McCartney ever bought was a Gene Vincent record. And as The Plastic Ono Band played those old hits, The Beatles road manger noticed the rock & roller crying. “It’s marvelous,” Vincent told him. “It’s fantastic, man.” After the show, Lennon says Vincent came up to him. “John, remember Hamburg, remember all that scene?”

But The Plastic Ono Band’s set was as much about the future as it was about the past. The experimentation and collaboration which would define Lennon’s solo career were on full display. Near the end of “Blue Suede Shoes”, Yoko came out, climbed into a white bag and sat down on the stage next to John. At the end of “Money (That’s What I Want)”, she climbed out and handed him the lyrics. When they started into “Yer Blues”, Yoko began to wail into a microphone. “It sounded as if she was crying, like a child, in fear,” the Globe and Mail wrote. After a stirring, sing-along rendition of “Give Peace A Chance” — the first big public performance of Lennon’s first solo song — the entire second half of the set was centered around Ono’s experimental sound-making. “Yoko’s going to do her thing all over you,” Lennon announced. Then she began to sing the bizarre noises of “Don’t Worry Kyoko (Mommy’s Only Looking For Her Hand In The Snow)”.

Some didn’t respond well to Ono’s avant-garde howling. One fan told Mojo Magazine, “People were polite. They were bewildered, but everybody knew she was an artist, she’d taken photographs of bums and things like that. We figured whatever she was doing, eventually it would end. But it didn’t fuckin end.” Ronnie Hawkins was there that night, too; he remembered people being a little less polite. “As hip as everyone there tried to be,” he says, “Yoko was too much. ‘Get the fuck off the stage,’ people started to scream.” Some people booed. The Star called it “excruciating… a finger nail scratching over a blackboard.”

But Lennon claimed he didn’t hear any of that. And Ono won some rave reviews. The Montreal Gazette called her performance “extraordinary… full of real emotion… the stunning effect of Yoko’s soaring cries [were] like worlds colliding or the universe blowing apart…” The entire set was recorded and released as an album called Live Peace In Toronto 1969. It broke the Top 10 on the Billboard chart and went gold. In Rolling Stone, Greil Marcus called it, “more fun than anything [Lennon]’s done in a long while, with a great deal more vitality than Abbey Road, in fact.”The set ended with the haunting shrieks of Ono’s “John, John, Let’s Hope For Peace.” As the song came to a close, Lennon leaned his guitar up against an amp, screaming feedback while Clapton coaxed strange noises from his own instrument. They left Yoko on stage, squawking like a bird into the Bloor Street night.

Lennon was thrilled with the way things had gone. “I can’t remember when I had such a good time,” he said later. “It gave me a great feeling, a feeling I haven’t had for a long time.” He’d been nervous and uncertain about the next stage in his life. But the show in Toronto had given him confidence. Now, he knew for sure he wanted to return to the stage. And it wouldn’t be with the band he’d been part of since he was 15 years old. No less of an authority than Ringo Starr cites the Toronto Peace Festival as the turning point: John Lennon was going to leave The Beatles.

So the final seeds had already been sown by the time the last act of the Rock ‘N’ Roll Revival Show finally took the stage. The Doors were past their peak, too. Jim Morrison had less than two years left to live. He was already awaiting trail for indecent exposure charges; in a few weeks, he’d be arrested again for being a drunken mess on an airplane. He was run down, ravaged by alcoholism. He’d grown a beard, gained weight; one fan remembers the sound of his knees cracking as he moved around the stage that night.

But the band played a mesmerizing set. “When The Music’s Over.” “Break On Through.” “Light My Fire.” In the Toronto Daily Star, Jack Batten gushed, “Jim Morrison has so much presence, so much electricity, that he makes his rock contemporaries resemble a collection of wax dummies…” Peter Goddard agreed in the Toronto Telegram: “With [Morrison] there was a sense of melodramatic theatrics, of sensuality and poetry, of sheer power belching electronically… With an icily sleepy stare and a slow amble, he was a force to be reckoned with…”

Before long, there was only one song left to go. As Ray Manzarek’s keyboards hummed darkly, the tambourine shook and the bass plucked away. Morrison leaned into the microphone, remembering how his own life had been changed by rock & roll. He shared his memories with the audience between languid, drugged-out pauses. “You know, I can remember when I was… in about the seventh or eighth grade… I can remember when rock & roll first came on the scene… it burst open whole new strange catacombs of wisdom… And that’s why for me this evening it’s been… really a great honour… to perform on the same stage… with so many illustrious musical geniuses.”

And then, Jim Morrison began to sing. It was the only song you could imagine ending the festival with. The only song you could imagine ending the decade with, really:

“This is the end, beautiful friend. This is the end, my only friend, the end. Of our elaborate plans, the end. Of everything that stands, the end…”

It was nearly two in the morning by the time the Toronto Rock ‘N’ Roll Revival Show finally came to an end. In the thirteen hours since the first act took the stage at Varsity Stadium, a lot of things had changed. The ’50s had been revived. The biggest band of the ’60s had entered their final days. Shock rock had been born. And so, too, maybe, had the tradition of an audience lifting their matches and lighters — and someday their smartphones — into the air. It’s no wonder Rolling Stone once called the Toronto Peace Festival the second most important event in the history of rock & roll.

A week later, John Lennon told The Beatles he was done. The greatest band of all-time was breaking up. The 1960s were over. The 1970s were ready to begin.

A version of this post originally appeared on the The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog. You can find more videos, photos, links, sources, and other related stories there.

One comment

This article is very well written. I have previously done a lot of research into this festival and wrote an article on it myself, but this one contains many details I was unaware of and paints a great picture of how important the “other” festival of 1969 was. Thanks for the great post.