A critically important conversation topic that we should begin to engage in is how we can strategically use the design of cities to positively impact mental health. This assertion may seem counter-intuitive given that cities are often associated with a number of factors that are popularly believed to agitate, and sometimes even spark some mental health illnesses: The noise pollution. The stressful hustle and bustle on public streets. The increasing disconnection between ourselves and our neighbours. The lack of affordable housing. The competition for well-paying and satisfying jobs in an unstable economy.

These and other popular, but not entirely accurate, perceptions about cities largely informed the ways that mental health facilities were designed, and also, the ways that people living with mental health issues were previously treated. Historically, mental health institutions were built outside of cities, enclosed behind high walls with overt surveillance, and no public thoroughfares. Recently, individuals have begun to reconsider the efficacy of this approach for a number of key reasons. Cities have undergone massive outgrowth and so areas formerly considered a “refuge” from the central core have become urbanized. At the same time mental practitioners and caregivers noticed that in-patients had a more difficult time reintegrating into their urban communities after being secluded during treatment. Also, designers recognized that brutalist and isolated building structures inadvertently reinforced discriminatory attitudes that people with mental health illnesses should be locked away.

Thankfully, our collective thinking has advanced in some important ways. Progressive mental health institutions like CAMH have dramatically transformed the sector’s approach to treating and collaborating with people living with mental health illnesses. Grassroots programs have organically emerged in local communities. Bell Canada exemplifies the growing commitment of corporations to openly discuss and raise funds for mental health illnesses. That stated, perceptions of the negative impact of cities on our mental health persists.

It is incumbent on professionals engaged in design and city building to work more closely with mental health professionals, youth, individuals living with mental health illnesses, educators, and other members of the community. In so doing we would be able to cull existing knowledge across disciplines and lived experiences. We would also be able to develop best practices and strategies, which show the ways that cities support mental health.

This is not to suggest that urban design, architecture, and citizen placemaking can “cure” mental health issues. However, there is growing evidence to suggest that urban places – physical and conceptual – can be used to support the 1 in 5 of us who will experience a mental health issue within our lifetime.

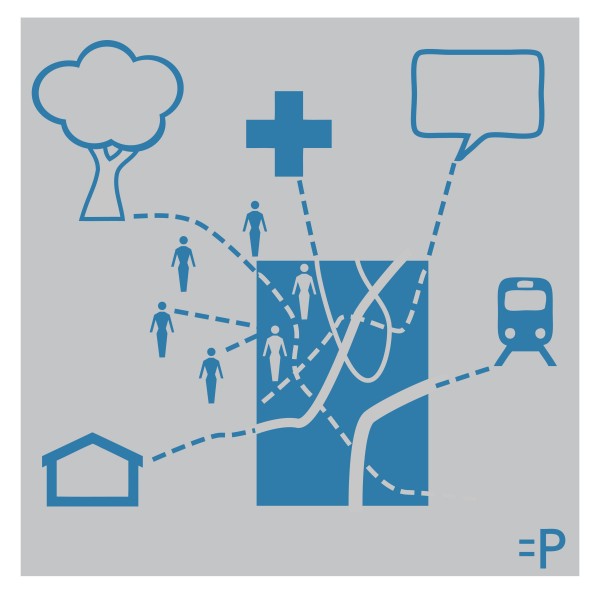

The first step to realizing this goal is by transcending narrow silos and collaborating across professional disciplines and lived experiences. Next, design and city building professionals must expand conversations pertaining to issues such as transportation, affordable housing, and migration to cities. Interestingly, these, and other issues, directly intersect with mental health determinants. For instance, transit plays an integral role in connecting people to work, social networks, and services, which all contribute to mental health and wellness. Instead of having polarized transit debates comparing Light Rail Transit (LRT) to subways, there should be deeper investigation into how each option facilitates the ability of people to be mobile in ways that support their mental health. Another example of an intersecting issue is urban development and revitalization. With an unprecedented number of the world’s population migrating to cities over the next couple of decades, we must design communities to support them. Given that migration, poverty, and culture are all mental health determinants, it will be important to address these factors through thoughtfully designed, affordable, mixed-use communities.

These, and a number of other examples make the case for designing cities that contribute to our collective mental health. As we continue to address these issues let’s look to the city as a resource. Urban ecologies provide us with new treatment facilities interwoven into city life. Informal gathering spaces and local hubs foster relationships. Transportation arteries and well-designed neighbourhoods are “connectors”, which promote accessibility. Built forms and strong local economies increase personal and community resilience. If these resources are optimized, design and city building may well emerge as an integral strategy for improving mental health.

Written by Jay Pitter and Adam Brander

7 comments

Less jargon and more plain speaking would be helpful, to start.

As a strong adherent of the principles of good design and as a public policy wonk who is passionate about mental health, I was so pleased to read this article. The authors have clearly understood how important it is to see people as part of and influenced by the environments in which we grow, live, work and play. Moreover, I appreciated another reality brought to light by this article: people design cities. Cities are not independent organic creatures that developed from a single spark. As such, people (we) can purposefully conceive of ways to build features into the places where we live to influence our lives. There is no default, less-than-ideal, approach that we need to accept. In fact, we see the approach described in this article replicated time-and-time again in many Scandinavian countries, where new communities are built based on the same principles of collaboration and cross-disciplinary consultation espoused in this article. So we know that what the authors are talking about is not only possible, but we can readily see the benefits of these collaborations on people’s mental health, physical health, nutrition, etc. Yes, while 1 in 5 will experience a mental health issue during our lifetime, and can benefit from the principles of good design, we must remember that we are not alone: 4 out of 5 people will also benefit from good (urban and other) design. I could not agree more with the authors: this is not about “curing” mental health issues. Good design is about increasing the positive elements that can be built into a community, a town or a city. These positive elements will affect all of us (5 out of 5), and have the potential to promote better ways of living, better ways of contributing to our families and communities, and better ways of avoiding preventable costs due to poor (urban and public policy) design.

The article starts out with the premise that “A critically important conversation topic that we should begin to engage in is how we can strategically use the design of cities to positively impact mental health.” But then offers almost no examples of how City design impacts mental health (save for the vagaries platitudes in the final paragraph) In fact there seems to be so little say on the topic that it drifts off to speak about concerns for the migrant. If the article is a call to action – propose some action. I have no choice to dismiss this effort as someone trying to marry the buzz words of urban design with buzz words of mental health.

As like Mark, I was so happy to come across this article. I think this topic is incredibly fascinating, and I believe bringing awareness to this connection between design (urban, industrial, architecture, landscape, etc.) and mental health is most important and relevant to today’s culture.

It brought to mind this quote by Jane Jacobs: “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”

So I guess that means Etobicoke will have to be completely redesigned.

A city like Toronto where condos and skyscrapers are mushrooming at an unprecedented pace poses some critical questions about where our city is headed. This issue is further compounded if the rate of development doesn’t take into account the big picture of what an affordable, liveable and vital city looks like. Jay and Adam’s piece fulfills an important job of checking and questioning this growth — a growth that could potentially render our city into nothing more than a COLD, money-making concrete jungle for real estate developers. Our collective responsibility in starting a conversation on the need for designing accessible urban spaces is never too late–by 2030, six out of every ten people in the world will live in an urban area. How will Toronto look by then? Well-written, incisive and timely. Thank you Jay and Adam!

Funding for innovative community based mental health programs and services such as WRAP is a great need.