These are the Blackdown Hills. They’re one of England’s official “Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty,” all rolling green hillsides and yellow fields and ancient trees lining roads so old they’ve worn deep groves into the ground. It’s a land of magic and of myth: of pixies and fairies, of warrior ghosts and witchcraft, of Druids and Romans, of poachers and smugglers, of Iron Age hill forts, Bronze Age burial mounds and Stone Age earthworks. And this is where the founders of Toronto fell in love.

The story of the Simcoes starts with a man named Samuel Graves. He was an Admiral in the British navy; he spent much of the 1700s fighting. He was the Captain of a ship during the Seven Years’ War and he was the head of the whole North American fleet during the early days of the American Revolution. That bit didn’t go very well: he was ordered to control the entire east coast of the United States with only a couple dozen ships. Those orders have gone down in history as one of the most impossible tasks ever asked of a naval officer. Graves was doomed to fail. Eventually, he was replaced and he headed home to his country estate, where he’d live out the rest of his days in relative peace and quiet.

His house — Hembury Fort House — was in the Blackdown Hills. In fact, it still is; it’s a retirement home now. And while Admiral Graves didn’t have any children of his own to take care of, he did have a niece. Her name was Elizabeth Posthuma Gwillim.

She was an orphan from the very beginning. Her father had been a military man, just like Graves. Thomas Gwillim had fought in Canada during the Seven Years’ War, as Aide-de-Camp to the legendary General James Wolfe. He was there at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, one of the most famous moments in all of Canadian history. And unlike Wolfe, he survived. But the Seven Years’ War had been raging on battlefields all over the world — it was the first truly global war; one of the bloodiest conflicts in human history. So after Canada, Thomas Gwillim was sent to Germany. And it was there, for a reason that has been lost to history, that he died.

He never knew that his wife was pregnant. It was a surprise: she was 38; they’d never had any other children. And soon, she would follow her husband to the grave. The strain of giving birth was too much for her. She lived just long enough to see her baby daughter before she passed away. That’s how the infant Elizabeth got her middle name — Posthuma — because both her parents were dead.

Growing up as an orphan, young Elizabeth spent her childhood living with relatives. Some were in Northamptonshire — in the middle of England, “the county of spires and squires” — where she was born. Some were in the verdant Wye Valley, on the border with Wales. But it seems that most of her time was spent with her uncle, Admiral Graves, in the Blackdown Hills. She became the daughter he never had.

“Elizabeth fell in love with the beautiful Devon landscape,” her biographer, Mary Beacock Fryer, writes, “which she grew to regard as her spiritual home. She roamed the rolling countryside, and the moor rising above the green fields with their underlayer of red sandy soil.” She went for long rides and walks through the hills, sketching the countryside and collecting plants. At home, she turned those sketches into watercolours and stayed up late reading or chatting with her best friend. Those same skills would eventually earn her an important place in Torontonian history — her diary, drawings and paintings provide a remarkable record of the founding of the city.

But Elizabeth wasn’t the only young person who shared the affections of the old Admiral. During his days in the Royal Navy, Graves had become friends with the captain of another ship: Captain John Simcoe. He, too, fought in Canada during the Seven Years’ War. But he never came home. He caught pneumonia just a few months before the Battle of the Plains of Abraham and was buried at sea near the mouth of the St. Lawrence River. He left a wife and two sons behind. The eldest was named after his father and got his middle name from his godfather, Admiral Graves. He was called John Graves Simcoe.

Simcoe followed in the footsteps of his father and his godfather, fighting for the British in North America. This time, it was during the American Revolution, where he quickly made a name for himself as one of the Redcoats’ most successful commanders. He adopted guerrilla tactics, never lost a battle, survived serious wounds and months in an American prison. But while he was gone, his mother died. Simcoe was still in his 20s — now he was an orphan, too.

After the war was over, he returned home to England to nurse his wounds. And since he didn’t have any immediate family left to stay with, he headed to his godfather’s house in the Blackdown Hills.

There’s a chance he might have already met Elizabeth by then. But even if he had, she would make a whole new impression now. She was 19 years old, pretty and slight, just about 5 feet tall. She could paint and draw and do needlework, was well-read and spoke three languages. And for his part, Simcoe was a dashing young officer in his late 20s, a hero of the war against the American rebels with political ambitions and a passionate interest in the distant Canadian colonies.

Simcoe, too, fell in love with the Blackdown Hills. He was fascinated by the history of the place — those stories of fairies and ghosts and smugglers. As soon as his wounds had healed enough, he started to join Elizabeth on her long walks through the countryside, up and down those big green hills. They would both make sketches of the picturesque landscape and turn them into full paintings when they returned home to Hembury Fort House. And while at first, they were accompanied by the Admiral’s wife — who was skeptical of the young relationship — soon, she let them go out on their own. They would stride down those ancient, sunken roads, with Elizabeth having to run every few steps in order to keep up with the tall soldier.

“From walks the couple graduated to long rides each morning before breakfast,” Fryer writes in her biography. “To Mrs. Graves’ chagrin, she found herself looking on, helpless, as the two were obviously falling in love. Admiral Graves was delighted with the train of events, and sought to give the couple every encouragement.”

It worked. Just a few months after Simcoe arrived in the Blackdown Hills, the two were engaged. It was the summer of 1782. That December, they made the short trip down the hill from Hembury Fort House to a nearby church in the tiny village of Buckerell. There, they were married in front of their friends and their surviving family members. With Elizabeth’s inheritance, they bought a beautiful estate of their own, just across the fields from Hembury, where they would raise their family. They spent the rest of their lives in the very same hills where they’d first fallen in love.

Except, of course, for one long trip to Canada, founding a new city in a new province in another land they loved.

All photos by Adam Bunch

A version of this post originally appeared on the The Toronto Dreams Project Historical Ephemera Blog as part of the Dreams Project’s recent tour tracing the history of Toronto in the UK. You can find more sources, links and related stories there.

3 comments

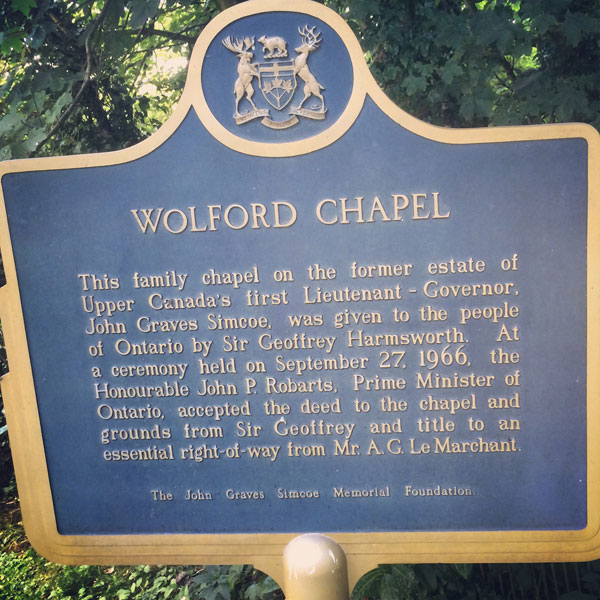

HA! Prime Minister of Ontario

Thanks, Adam. Most of us don’t know enough about these two.

Mind you, there’s a new TV series that Torontonians don’t seem to have noticed depicts Simcoe when he was a young British officer in the US Revolutionary War: “Turn: Washington’s Spies” depicts Simcoe as a pretty nasty guy. The series is based on a history book, by former National Post writer Alexander Rose, but he acknowledges some incidents in the TV series are invented for dramatic purposes. (Turn’s first season is being re-broadcast now, Saturdays at 10pm.)

One caveat to your article. I thought we were past speaking of “Toronto’s earliest days” being only 200 odd years ago, as if Europeans “discovered” this place. Toronto has been inhabited for at least 10,000 years and it’s time to move past the Us vs. Them assumption buried in statements about Toronto’s beginnings only 200 years ago. Toronto — Ontario — Canada, the very names of this place are all from Indigenous languages. A more inclusive, and more interesting, history of this place needs to be told and understood by all of us. Books by Ronald Williamson, Donald B. Smith, the new app First Story Toronto, and attending events hosted by First Nations organizations in Toronto are places to start.

You’re absolutely right, Brian. Thanks for catching that! I’m not usually so sloppy with my wording. I’ve changed that sentence — here and on the Dreams Project blog — to make it clear I mean the founding of the city itself.