There’s ancient Lake Iroquois sand on Glen Davis Crescent near Kingston Rd. and Woodbine Ave., you just have to look closely to see it. A clue to its source comes in the faint sound of water bubbling from the storm drains on the north side of the street.

A creek has been rising here for thousands of years, carving a steep natural bowl out of the supple land. The water once flowed southwest in a shallow valley to Small’s Pond, a serpentine body of water popular with skaters and boaters near today’s Queen St. E and Kingston Rd. before trickling out into Lake Ontario.

Today, the bowl at the source of the creek is lined with old-growth oak, sassafras, and witch hazel, but the city has encroached on this formerly tranquil rural oasis. Glen Davis Cres., a residential street laid out in the 1940s, runs along the valley floor and a brick apartment building on Kingston Rd. looms large at top of the southern slope.

The biggest change, however, concerns the stream. It’s gone, though it would be inaccurate to label it lost.

Tomlin’s Creek, to use its proper name, was channeled into a sewer like so many of the small rivers and streams that used to flow through Toronto. What makes Tomlin’s special, however, are its repeated attempts at a comeback. Until a few weeks ago, the creek was emerging in a front yard on the north side of Glen Davis and flowing down the street.

Tomlin’s isn’t big (it would be easy to mistake the flow of water for a leaky garden hose,) but thanks to its connection to a complex system of underground aquifers, it’s reliable. On my first visit, a layer of green algae had formed on the road surface, providing a hint at how long it had been flowing.

Kip McCaskill lives on Glen Davis Cres. close to Tomlin’s Creek. He became an expert on the lost river and its ravine during a protracted and ultimately unsuccessful fight against a six-storey condo that will soon overlooking his back yard.

He tells me how before the street was developed in the 1940s, the ravine was home to a small farm and community garden. “They grew all kinds of food. That was post-war … we think the access to it was off Kingston Road,” he says. There was a barn with horses and other animals.

The ravine and street are named after Emma Davis, an early landowner. Her ravine was donated to the city in 1945 on the proviso it be used as a public park, but the agreement didn’t last long.

The city quickly sold up and residential development began in 1946. Tomlin’s Creek was channeled into a sewer and a series of detached, south facing bungalows were erected. A decade later Glen Davis was developed on both sides, save for a small parcel of land sandwiched between the backyards of Kingston Rd. and Glen Davis Cres. that was still officially designated a park.

That too was sold off, despite protests from local residents, in 1954. The parks commissioner at the time said small parcels of parkland like the one used by the Glen Davis neighbourhood kids were too expensive for the city to maintain.

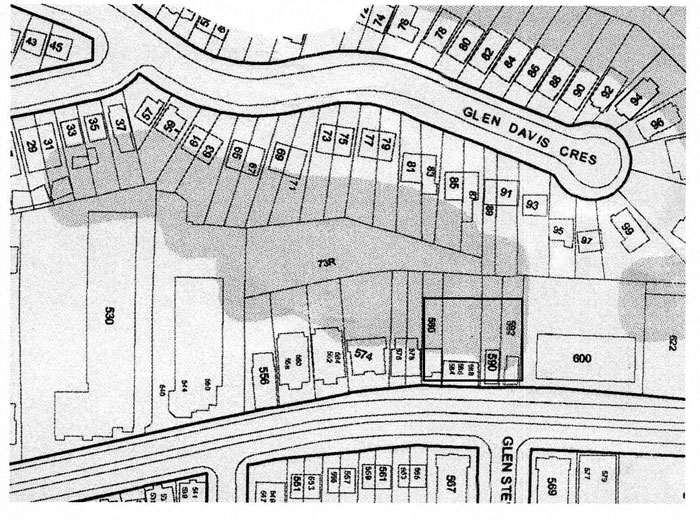

Unlike the rest of the street, the former park was never developed, and today the only access is through one of several nearby backyards. “It’s in the middle of nowhere,” McCaskill says, pointing to the roughly triangular shaped lot 73R on a map (above.) “It has no frontage.” Some local residents have dug small vegetable gardens on it, but mostly it’s covered in trees felled by last year’s ice storm or cut down to make way for the development McCaskill and the Friends of Glen Davis fought so hard to stop.

Despite the encroachment of housing, Tomlin’s Creek refuses to die. The spring has surfaced in various locations since it was first buried, but most recently it was in the front yard of number 92, the water spilling into the gutter and flowing into the nearest drain.

McCaskill tells me tales of basements undermined by shifting sand and busy sump pumps. He says one resident doesn’t have to shovel his drive in winter because the warmth of the natural spring keeps the concrete surface above freezing.

Unfortunately for anyone hoping to visit Tomlin’s Creek, shortly before writing the city dug up the north end of Glen Davis Cres. and ushered the stream back underground (it’s still visible on Google Street View, however.)

All that remains on the surface is the sound of rushing water in the drains, but have no doubt, Tomlin’s will almost certainly return.

Images: City of Toronto Archives, Chris Bateman

3 comments

Wet basement? Maybe there is (maybe hidden) a creek somewhere nearby.

interesting article – take a walk a block west in to Cassells Park. It seems that an underground stream is starting to reemerge there also.

I’m always happy to see lost creeks & brooks re-emerge,

Walmsley Brook made things very difficult for an infill housing builder on Walder Ave near Bayview and Eglinton.