Last month, I joined a Lost Rivers walk within the PATH system.

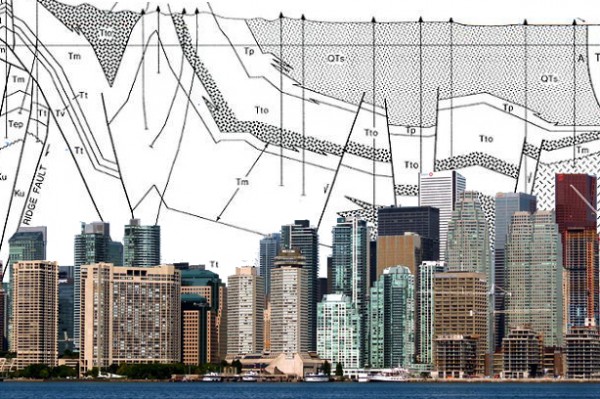

Typically engaged with tracing the routes of buried creeks within Toronto’s topography, the Lost Rivers PATH walk was unique in its investigation of a part of the city so thoroughly urbanized that finding traces of what came before seems absurd.

In its third year of hosting the PATHology and Geology walk, Lost Rivers has once again invited a reconsideration of Toronto’s urbanized core. Our goal was finding proxies for — and true instances of — nature within the world’s largest network of underground pathways.

Lead by geologist John Wilson, our group learned about the origins of the stone that clads the interior spaces and exterior facades of Toronto’s largest skyscrapers. Stopping to appreciate nature-inspired art along the way, we also found evidence of one of the many streams that used to flow through the centre of the city.

It turns out that most of the stone cladding in Toronto comes from very far away. Despite being just south of the Canadian Shield, Toronto’s skyscrapers are covered in stones from further afield, like red granite from Sweden (Scotiabank Plaza), travertine from Italy (the lobby of the TD Centre) and marble from Kashmir (the tunnel west of Scotiabank).

Thinking about the sheer volume of stone mined from the earth, shipped across the planet and reconstituted as Torontonian skyscrapers, it’s easy to appreciate that our modern city is a geologic force as strong as those that created the Scarborough Bluffs and carved the ravines.

Sometimes, the geologic forces of urbanization are more subtle. When the initial construction of the Bay-Adelaide centre was delayed indefinitely in the early 1990s, the city was left with a 6-storey stump and an unfulfilled order of 35,000 tons of Norwegian granite. Without the 44-storey tower to be clad, the city was awash in free flowing Scandinavian stone that has since settled into hundreds of tables and floors in downtown Toronto.

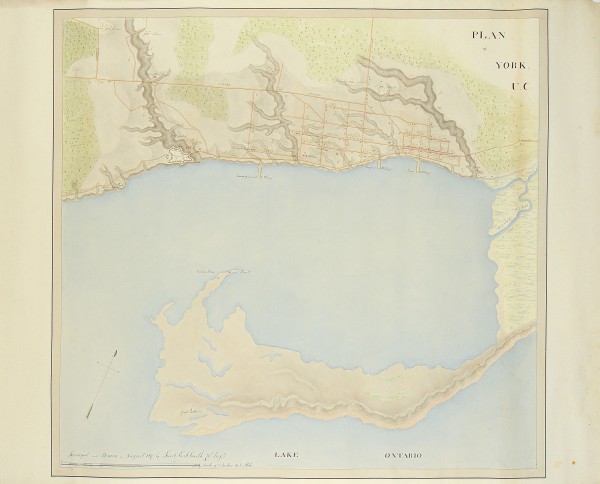

Beneath the city covered in layers of stone from elsewhere, there are indeed remnants of historical watercourses. Though most of the waterways in downtown Toronto have been eradicated due to extreme excavation for infrastructure and subterranean parking levels, a proxy for one of the Market Streams that used to flow south east through the city does exist.

In the corridor between the Royal Bank Building and Brookfield Place, the stone below our feet was showing signs of water absorption. This would have been where Newgate Creek emptied into Lake Ontario.

Though dry to the touch, the off-coloured stone might be a sign of the groundwater that would have replaced the creek. Standing underground, surrounded by concrete, it’s powerful to feel this rare assertion of the landscape beneath Toronto — a sign of the city before the glass, steel and international stone of today’s internationally constituted metropolis.

Check out Lost Rivers‘ website for upcoming walks.

The idea that Toronto is a geologic force was inspired by Geologic City: A Field Guide to the GeoArchitecture of New York City by Friends of the Pleistocene and Smudge Studios

Daniel Rotsztain is the Urban Geographer. Check out his website or say hello on Twitter!

2 comments

Glad this touched on the tonnage of buildings, and the far-flung sourcing of much of it. There is a vast accumulation of energy in that mega-tonnage too, which is usually uncounted in GHG counts and is wasted with demolition or much renovation. Demolitions are urban oil spills, especially if the building is/was sound and well-built to last for decades and beyond.

This is really interesting. Thank you for posting it.

I spotted a typo: “story” should be “storey” (as in “6-storey” and “44-storey”).