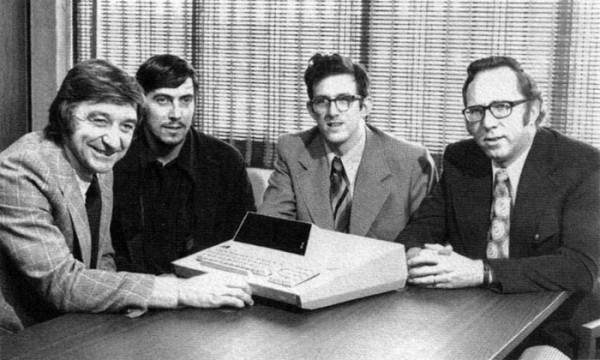

The Royal York Hotel, September 25, 1973. Computer experts Mers Kutt, Gordon Ramer, Ted Edwards, and Reg Rea are standing around a small machine about the size of a typewriter. It has a built in QWERTY keyboard, a small plasma display, and looks like one of the oversized desktop calculators common during the 1960s.

This was, however, much more than a simple adding machine.

The Toronto-made MCM/70 was the first personal computer to be designed for use by the public. Two years before Bill Gates and Microsoft, three before the Apple I, Micro Computer Machines Inc. near Sheppard and Victoria Park had produced a portable device they believed was capable of launching the PC revolution.

The story of the MCM/70 begins in December, 1971 with the formation of Kutt Systems Inc. Mers Kutt, the company’s president and namesake, was an Winnipeg, Manitoba-born computer expert who had recently been forced out of Consolidated Computer Inc., a wildly successful business he helped establish in 1969.

In the 1960s, entering data into large, mainframe computers was mostly done using punch cards, a laborious, time-consuming, and frustrating process. CCI’s Key-Edit 100 system allowed users to easily input information (and, crucially, quickly correct errors) via a simple keyboard and display.

More than 30,000 of the terminals were installed in 28 countries around the world, and CCI was seen as a symbol of Canada’s newfound technological prowess. However, in 1971, just months after his wife died of cancer, Kutt was squeezed out of CCI.

“He could easily have secured a top position with one of the North American computer manufacturers,” writes York University associate professor of computer science Zbigniew Stachniak in his book Inventing the PC: The MCM/70 Story, but the dream of creating a scaled down computer for personal use proved too hard to resist.

“I was always more attracted to the things they said could not be done,” Kutt said.

The first obstacle to overcome was size. Standard mainframe computers, like the UNIVAC 1107 that managed Toronto’s traffic lights, occupied entire rooms and required elaborate air conditioning systems to keep them cool. The sheer size and cost meant they were only practical for large businesses, like banks or insurance companies.

What made Kutt’s idea viable was the invention of the microprocessor in the early 1970s. The little chips scaled down much of the architecture of mainframe computers into just a few circuits, resulting in dramatic space savings. Kutt thought the Intel 8008, an 8-bit microprocessor released in 1972, might be able to power a computer small enough to fit within the confines of a desk and still run basic applications.

Another problem was software. The standard operating systems of the day were designed for high-spec machines. Like trying to run the latest iOS release on a first generation iPhone, off-the-shelf software threatened to render even a high-spec Kutt PC useless.

To tackle this conundrum, Kutt recruited programmer Gordon Ramer to write code for the MCM/70.

More than a decade before MS-DOS, the text-based operating system used on the first generation of IBM PCs, interaction between human and computer was performed using a variety of languages, one of which was called APL—short for “A Programming Language.”

Before joining Kutt Systems, Ramer was able to create a simplified version of APL that used less memory and was therefore practical for smaller machines with lower specifications. He called it “York APL,” after York University Computer Centre.

With electronic engineer José Laraya, Kutt and Ramer produced the first functional version of the MCM/70 in Laraya’s Kingston basement in 1972. The rudimentary machine worked with the Intel 8008 chip and was capable of making basic calculations. On 11 November, the company was renamed Micro Computer Machines, Inc. and the prototype presented to the shareholders. They dubbed it the MCM/70, reflecting the new name of the company.

A portable version of the MCM/70 was shown at the Fifth Annual MCM Users’ Conference in Toronto in May 1973. “It was heating up,” recalled Ramer to writer Zbigniew Stachniak in The MCM/70 Story. “The demo had to be interspersed with short talks to allow José [Laraya] to exchange the heat-sensitive parts and then restart the system for the next segment of the demo.”

It was a far cry from today’s slickly produced Apple product launches, but the presentation attracted the attention of IBM and Intel, the company that supplied chips for the machine. “[Intel] didn’t believe that this little chip they were producing could do this much,” Kutt recalled in Stachniak’s book. Intel co-founders Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore particularly liked a horse racing game the MCM/70 could run on its one-line display.

The MCM/70 went through several revisions before the final product was ready for its public unveiling. A virtual memory function was added, allowing data stored on cassette tapes to temporarily boost the performance of the machine, and so was an on/off switch controlled by the operating system. For the first time, users could power down the machines without flipping a switch or pressing a button.

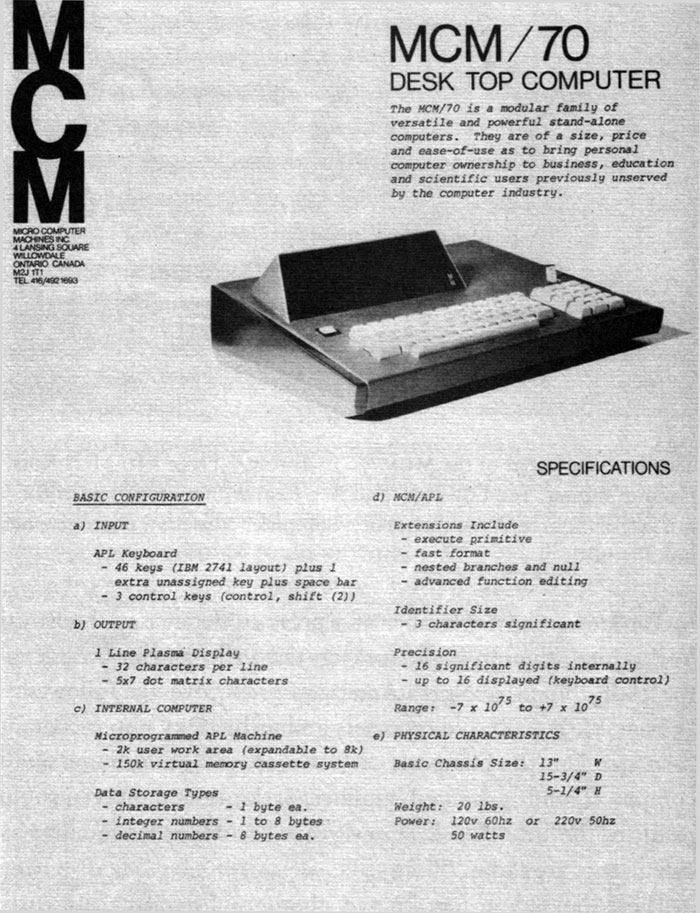

Completed in 1974, the final production model comprised a keyboard, one-line plasma display, and back-up battery for use in the event of a power failure. The system could be readied for use with the push of a single button and support a variety of external devices, including a printer.

Following its official unveiling in Toronto, the MCM/70 started shipping to customers late in 1974.

Early successes were hard to come by, however. Sales didn’t match investors’ predictions and Mers Kutt was forced out of a company in 1974. There were serious technical issues too: the plastic case wasn’t perfect, the motor for the built-in cassette reader was unreliable, but it was the power supply that almost wrecked MCM.

Designed in-house, the device plugged into a standard wall socket and controlled the flow electricity into the computer. If there was a sudden loss of power it was supposed to automatically engage the reserve battery, but prototypes given to potential distributor clients sometimes smoked or blew fuses. The design issue “shut the company down and created a serious financial crisis,” wrote Stachniak.

By the time it was resolved, Kutt and other key employees had already departed.

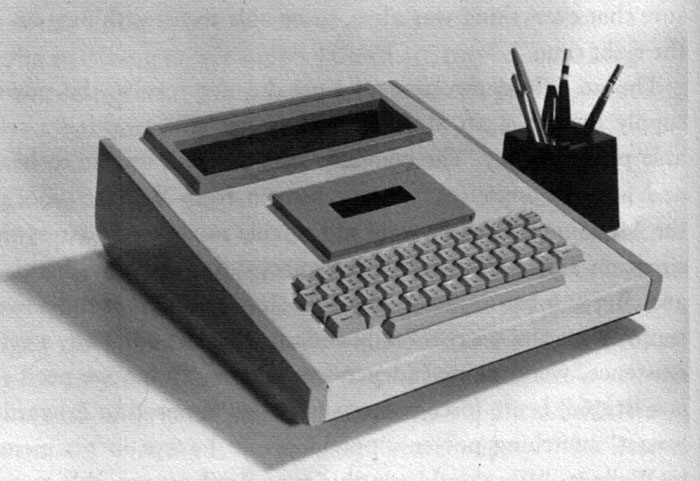

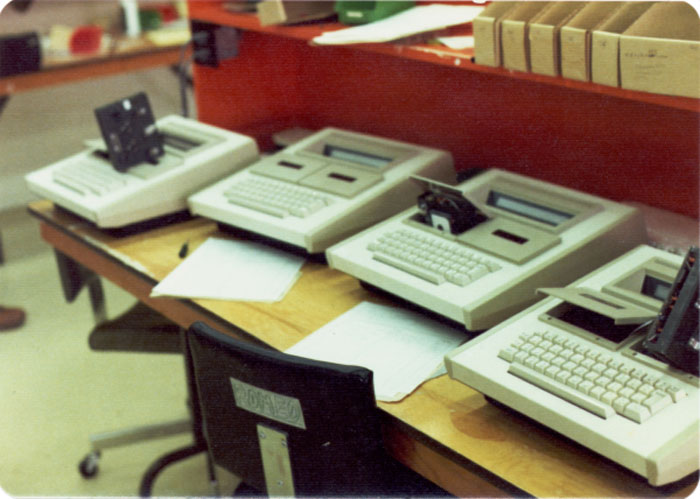

MCM issued several upgrades, including the MCM/700, which could support an external display, floppy disc drive, and modem, and the 1976 MCM/800 that resembled a modern day desktop computer, compete with a full-sized screen. Both cost more than $10,000 each. (The first /800 cost closer to $20,000.)

/800s were bought by the Department of National Defence for war-game simulations, Ontario Hydro to use at the Pickering nuclear plant, the University of Toronto, and various insurance companies, but competition from rival IBM would eventually snuff out the company.

The /900 and Power followed in the late 1970s, but MCM increasingly found itself on the wrong side of history by doggedly sticking with the APL language.

“We were against the tide,” recalled last company president and CEO, Birnam John Finch Woods, in MCM/70 Story. “The tide for APL and all that was on its way out to the ocean somewhere to be dropped and never seen again. At that point in time the operating system of the day was Microsoft [DOS].”

MCM folded in 1982, minus Kutt. In 2006, he told the Toronto Star he never intended to make history with the MCM/70. “You don’t think of that particularly when you’re developing it, you just do something you think is pretty neat.”

It was IBM, Xerox, and Hewlett-Packard—MCM’s richer, more stable American rivals—that ultimately prevailed in the race to popularize the personal computer. With the company Mers Kutt founded long dead and buried, the pioneering little MCM/70 was largely forgotten outside tech circles.

Now, happily, York University’s Computer Museum is working to restore the Canadian PC’s place in the collective memory. Zbigniew Stachniak’s book, published in 2011, details the myriad human and technological factors that played a part in the life and death of MCM/70, and is well worth a read.

There’s also an online exhibit.

One comment

Fascinating read. Thanks, Chris.