At Dundas West and Shaw, near Trinity-Bellwoods Park, there’s a conspicuous piece of Canada’s Cold War history.

On top of a 15-metre pole sits a massive electric air raid siren. Disconnected long ago, it’s one of just a handful of relics left over from when Toronto and the rest of Canada was seriously concerned about being caught up in a nuclear war between the United States and the USSR.

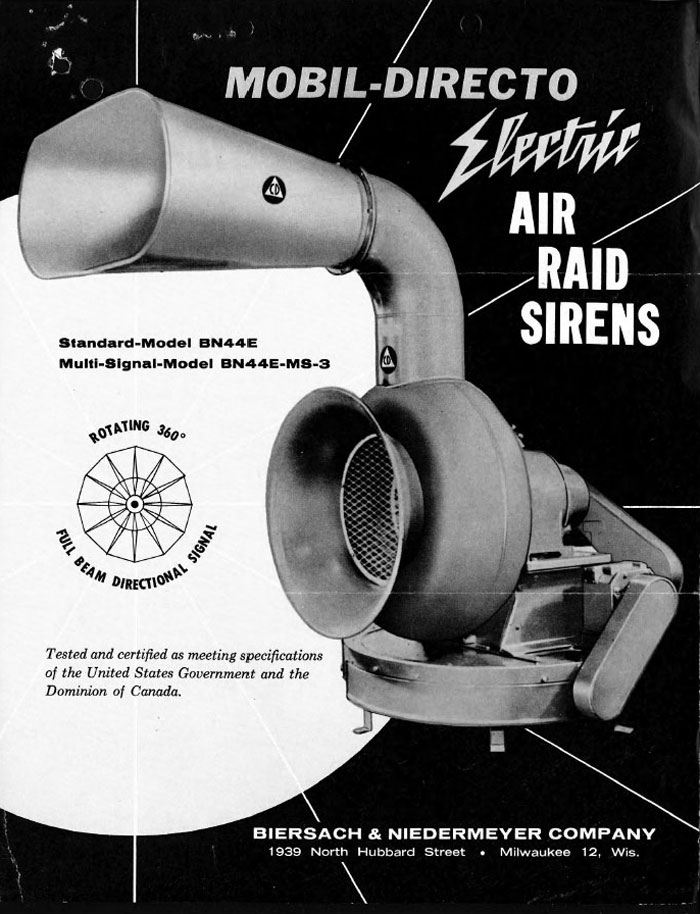

The idea of a peacetime, nationwide air raid alert system started in earnest in 1951, when the federal government under prime minister Louis St. Laurent commissioned 200 of electric, two-tone sirens from Scarborough company Canadian Line Materials, Ltd..

Provincial secretary Arthur Welsh said a co-ordinated system of sirens within the larger Greater Toronto Area would help in the event of a nuclear attack. “A bomb is not a respecter of municipal boundaries,” he said in 1951, adding that there was no plan to evacuate towns and cities in advance of an attack.

“Many people think some welfare organization would evacuate them, where they would be fed and clothed. That is not the case. In the past two wars, when soldiers in the trenches were attacked by mortar, they stayed and fought it out. That’s what we will do.”

The sirens would sound in the event of an imminent nuclear bomb attack or if there was danger from drifting radioactive fallout, perhaps from an attack on Detroit, Buffalo, or another U.S. target close to Toronto.

In March, 1952, the first six Canadian cities—Halifax, St. John, Montreal, Winnipeg, Vancouver, and Victoria—received their warning sirens. Toronto received a shipment as well, but refused to proceed with installation without money from other levels of government.

“Toronto just doesn’t seem able to get interested in [civil defence,]” officials in Ottawa complained.

By 1953, sirens were emitting mournful test wails in smaller Ontario towns, like Hamilton. In Toronto, the $750 devices were gathering dust in a firehall on Howland Ave. because the local authorities still refused to pay the cost of installation.

Besides, the city wasn’t sure the sirens would even save lives. In the event of a nuclear or hydrogen bomb attack, much of Toronto would be reduced to ashes in seconds. There would be no time for citizens to hear a warning and take shelter.

(That said, a news report in 1951 suggested Toronto’s suburban sprawl might protect against widespread loss of life in the event of a nuke hitting downtown. “Toronto is a city of home-owners. Its homes are scattered up and down hills and ravines over a wide area.”)

Before the Diefenbaker government, responsibility for Toronto’s disaster response fell to a cash-strapped organization with just three full-time staff. The Toronto and York Civilian Defence Committee, which relied on roughly 3,500 trained volunteers, had an annual budget of $16,000 in 1954—roughly 8 percent of the amount allotted for the same purpose in Vancouver.

A lack of equipment was also a problem.

“Without a control centre, a communications centre, or a warning system, the civilian defence officials, if an attack came today, would have at their disposal, in addition to telephones, some 700 to 800 taxis, equipped with two-way radio,” the Globe and Mail reported. “These would be effective only if their control centres remained in operation.”

“Starved for money and staff, Toronto’s civilian defence officials frankly admit they would be caught cold unless there was plenty of advance warning of an attack,” the story continued, ominously.

Ottawa asked Toronto to return its unused sirens later in 1954, and that appeared to spur the city into action. A report suggested the 30 units could be installed for just $20 each, but still nothing was done by 1956. Toronto complained the electric sirens were too quiet, especially in the winter when people added storm protection to their homes, and susceptible to failure in the event of a power outage.

A new batch arrived courtesy of the federal government later that year, though they weren’t the American-made Thunderbolt model the City of Toronto wanted. The first 25 additional units arrived in Toronto in the Fall of 1956 and were installed along with those held in storage around the end of the year.

The first pubic test took place on December 7, 1956, when a siren mounted on top of a building at Yonge and Richmond wailed to life. It was audible up to six miles away in some parts of the city, but almost impossible to hear on nearby Court St., proving the suspicions of civil defence officials.

Tall downtown buildings threatened to deflect the important warning sound away from its intended target, and so many were installed on 15-metre poles where rooftops were unavailable or too expensive to lease.

Despite progress, Toronto’s system of air raid sirens was still incomplete in 1958 and remained untested into 1960. Under the jurisdiction of the army, the first full scale test was conducted in December of that year. According to the results, up to a quarter of the city was unable to hear it, partly due to several electrical malfunctions.

The air raid system was controlled through the telephone network using special system developed by Bell. Called the Bell and Lights System, it consisted of a central control unit based on a modified handset.

“The dial is like any ordinary telephone dial, but it has a colour code in place of letters and numbers,” The Globe and Mail reported in 1952. “Dialling of yellow transmits a confidential alert or warning that an attack may take place; red indicates an attack is imminent, white is all clear.”

Sirens were controlled through the addition of a second circuit connected to the dial and every phone book in Toronto carried an explanation of what to do when the siren sounded.

Though innovative at the time, the Bell system soon began to show its age. In 1967, a fault at a downtown telephone exchange triggered dozens of sirens across the city for about 10 minutes. The police were flooded with calls, though no-one was scared, according to reports.

“The only thing that panics people here is when the Leafs lose 10 straight,” a police official said.

As the threat of nuclear war diminished through the 70s and 80s, the Ontario siren system began to fall into disrepair. Lightning strikes and damage by vandals with rifles triggered periodical false alarms. In 1979, a badly timed activation of 50 sirens between Port Credit and Oshawa caused nervous moments for several local residents.

“Some called police and local media to ask whether the alarm was a warning that SkyLab was about to fall on Toronto, ” the Globe and Mail reported.

By 1980, there were 1,704 sirens dotted across the country, according to the Toronto Star. “Most of the sirens have gone the way of the wind, or torn down with utility poles when lines and poles were replaced.” The downtown siren at Yonge and Richmond was still standing at the time, though it now seems to be gone.

The number of planned tests declined and were halted altogether in 1985 due to the changing “public sensibility,” according to emergency planning officials. A $4 million replacement that could have warned of imminent natural and man-made disasters was considered in 1986, but was never purchased.

From about 78 sirens in Toronto 1980, there are now just a handful dotted around the city, collecting rust. There’s one on the roof of the Harbourfront Centre and another on a former police station on Main St. The Victoria Building at Ryerson has a yellow siren at its northeast corner and a pole next to the tennis courts at Bayview Village Park on Bayview Ave. also houses a defunct siren.

Mercifully, none have ever been needed.

3 comments

“no-one was scared, according to reports.”

No one checked with the 11 year old me. I remember at least a couple of false alarms – though not necessarily the 1967 incident. I was terrified until the alarm was turned off. Of course even the adults didn’t understand the devastation of nuclear war in those days. If the unthinkable ever happens – the best thing to be is dead.

There used to be one of those devices mounted on a pole near St. Laurent Mall in eastern Ottawa. It got taken down to make room for the Transitway tunnel under the mall, if memory serves. (And if it doesn’t, I could do with a memory correction!)

fascinating to see relics of a possible nuclear war, but also incredibly chilling.